Allen Collins, a name synonymous with the raw, electrifying sound of Lynyrd Skynyrd, was more than just a guitarist; he was a force of nature. For those who witnessed Lynyrd Skynyrd in their prime, the image of Collins wielding his guitar, delivering blistering solos, is forever etched in rock history. But beyond the stage persona and the iconic “Allen Collins Guitar” riffs, lay a complex individual, as this personal account reveals through a series of unforgettable encounters with the Southern rock legend.

My first glimpse of Allen Collins was back in 1969, a time when Jacksonville’s music scene was buzzing with raw talent. I was with a group of fellow hippies, venturing into the Comic Book Club downtown, a spot where One Percent, the band that would soon become Lynyrd Skynyrd, held court. Our mission that night was less about music and more about acquiring some acid, but it was Collins who immediately captured my attention.

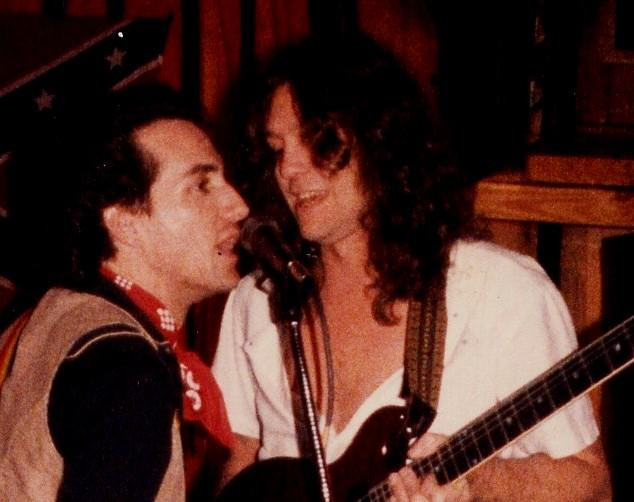

He stood outside the club, leaning against a wall, a striking figure in all white. Long and lean, he resembled John Lennon from The Beatles’ Abbey Road cover. This all-white ensemble became his signature style for a while, complete with white tennis shoes, the kind typically worn by women. Topping off this unique look was a massive mane of shoulder-length, curly hair. Even then, before the world knew the name Lynyrd Skynyrd, Collins exuded a rockstar aura, a visual embodiment of the raw energy that would soon define his guitar playing and stage presence.

A few days later, my friends and I experienced the aforementioned acid. It was a Friday night, and we found ourselves at the Sugar Bowl, a teen club nestled in Cedar Hills, a working-class neighborhood that nurtured several prominent musicians. Besides Collins, Cedar Hills was home to future Skynyrd members Leon Wilkeson and Billy Powell, as well as .38 Special’s guitarist Jeff Carlisi and singer-guitarist Don Barnes, and keyboardist Kevin Elson, who later became a renowned sound mixer, recording engineer, and producer. The Sugar Bowl was a breeding ground for Jacksonville’s rock royalty, and on this particular night, One Percent, on the cusp of becoming Lynyrd Skynyrd, was the main act.

The night took a turn when a group of local rednecks stormed the club, their presence immediately creating tension. They began harassing the hippies, sparking a confrontation with an off-duty police officer working security. The situation escalated quickly; someone brandished a knife, and more police officers materialized. As the acid began to kick in, my friends and I decided it was time to leave, escaping the chaos erupting at the Sugar Bowl. Even amidst the turmoil, the raw energy of One Percent’s music, fueled by Collins’ guitar, was palpable, a foreshadowing of the musical force Lynyrd Skynyrd would become.

Years later, in 1978, a year after the tragic plane crash that shook Lynyrd Skynyrd and the music world, I had another encounter with Allen Collins. My second wife and I were living in Murray Hill, a quiet Jacksonville neighborhood. We were grabbing a bite at Church’s Chicken on Cassat Avenue and Plymouth Street when Collins walked in and stood in line behind me. He seemed to recognize me, a flicker of familiarity in his eyes. I mentioned knowing Leon Wilkeson, whom I had met at the Forrest Inn during his time with King James Version, an earlier band of Wilkeson’s.

Collins joined my wife and me at our table. As we were about to leave, he casually asked if I knew where he could find a junk car for around a hundred dollars. He explained that he enjoyed taking them out to the woods and rolling them – his peculiar idea of recreation. This anecdote, though seemingly trivial, reveals a glimpse into Collins’ impulsive and perhaps self-destructive nature, a trait that contrasted sharply with the precision and artistry of his guitar playing.

Not long after this chicken-joint encounter, I met Marion “Sister” Van Zant, the matriarch of the Van Zant family, at a Dunkin’ Donuts up the street where she worked as a waitress. This was still a year after the Skynyrd plane crash, and the tragedy hung heavy in the Jacksonville air. Sister Van Zant, a warm and welcoming woman, invited me to the Van Zant family home and introduced me to her sons, Donnie and Johnny. I had previously met Donnie back in 1970 when I auditioned for Sweet Rooster, a band that later evolved into .38 Special, at Kevin Elson’s parents’ house.

I recounted my Church’s Chicken meeting with Collins to Sister Van Zant. She chuckled and remarked that Collins was a “disaster behind the wheel.” She then shared a story Johnny Van Zant had told her: Johnny had recently been pulling out of the Krystal on San Juan Avenue when a crazy driver in the wrong lane nearly ran him off the road. Johnny honked, and the driver responded with a middle finger. The offending driver, of course, was Allen Collins. These stories, circulating within Jacksonville’s music circles, painted a picture of Collins as a talented but volatile figure, a rock star living life on the edge, both on and off stage. His guitar playing, however, remained a constant source of brilliance amidst the chaos.

By early 1985, I found myself working with Filthy Phil Price and drummer-singer Carl De Blasio at Mac’s Mustang Lounge, a local Jacksonville bar.

One night, Allen Collins walked into the bar with his drummer-driver, Steve Reynolds.

Apparently, Collins liked what he heard. He and Reynolds returned the next night and again the following weekend. I recall it being late February because Collins decided to throw a pie at me on my birthday. Lynyrd Skynyrd had a tradition that anyone celebrating a birthday was destined for a pie in the face. I was on stage when Collins rushed towards me, key lime pie in hand. I ducked, narrowly avoiding the dessert projectile, but the key lime goo splattered all over my Echoplex. He laughed, but I failed to see the humor. That Echoplex unit had cost me $150, a significant sum for me at the time, and it was now ruined beyond repair. Despite the costly prank, it was clear Collins’ gesture, however misguided, was meant affectionately, a bizarre form of rockstar camaraderie.

Collins, it turned out, was planning to put together a new Allen Collins Band and wanted me as the lead singer and second guitarist. He also needed a bass player, and Price was offered the position. Collins already had a drummer, Reynolds, who also served as his chauffeur, leaving De Blasio out of the project. The need for a chauffeur stemmed from Collins’ revoked driver’s license, a consequence of his well-documented issues behind the wheel.

Reynolds and Collins picked up Price and me to take us to Collins’ estate in Mandarin, a more secluded area of Jacksonville. En route, Collins suddenly declared he wanted to drive. The next thing we knew, we were careening through a 7-11 parking lot at 50 miles per hour. Trying to maintain composure, realizing this was likely a mind game, I calmly said, “Allen, who is going to clean up your nice leather seats?”

“What do you mean?” he replied, feigning innocence.

“I mean you are scaring the shit out of us.”

He cackled, clearly enjoying our discomfort.

“Allen, if you want to kill yourself, that’s fine, but please don’t take us with you.”

He turned back to face us, left hand still on the wheel, maintaining the reckless speed. “Ah, ya buncha pussies.” This incident perfectly encapsulated Collins’ daredevil personality, a stark contrast to the meticulous craftsmanship he displayed when playing his guitar.

Seeking stability and survival, Price, De Blasio, and I decided to head to Vidalia, Georgia, to become the weekend house band at the Golden Nugget, a medium-sized nightclub. After a few weeks, Di Blasio vanished. Perhaps resentment over being excluded from Collins’ new band played a role. Price and I arrived at the club one afternoon to find the drums and sound system, De Blasio’s property, gone.

Fortunately, a band down the street had just experienced a falling out, leaving an excellent drummer and singer with a decent sound system available. His name was Scott Sisson. He joined our band that very afternoon, literally saving the day.

Collins and Reynolds drove up from Jacksonville to see us play on a Saturday night. We all gathered at Sisson’s house in Lyons that afternoon. Collins, in a moment of musical generosity, showed me the “correct” way to play the riff to The Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time.” He claimed Keith Richards himself had taught it to him personally, a credible claim considering The Rolling Stones and Lynyrd Skynyrd once shared the same manager, Peter Rudge. This instance highlighted Collins’ deep musical knowledge and his connection to the broader rock and roll world, a world he navigated with both brilliance and recklessness.

Collins also boasted about having “boinked” Chaka Khan on Skynyrd’s tour bus. This was noteworthy because certain Skynyrd members were known for their bigotry. However, Collins, in my experience, did not seem to share those prejudices. His personality was complex and contradictory, a mix of musical genius and self-destructive tendencies.

Suddenly, Collins spotted some pills on a coffee table, grabbed a handful, and swallowed them. Sisson’s wife exclaimed, “Allen, you eejit! ‘Em were my birth-control pills!” Collins simply grinned like the Cheshire Cat and shrugged, seemingly unfazed by his mistake.

I made a comment that Collins didn’t appreciate – I can’t recall the specifics – and he retorted, “Fuck you, you Jimmy Dougherty-lookin’ motherfucker,” and hurled a half-full Heineken bottle at my head. Jimmy Dougherty was the previous lead singer for the Allen Collins Band. The bottle whizzed past my ear, narrowly missing me, and sailed butt-first through the drywall, lodging itself with its neck sticking out.

Alt text: Allen Collins performing with a guitar, close up shot highlighting his hands on the fretboard and the body of the guitar, likely a Gibson Les Paul, in a live concert setting.

I should have quit then and there, but the allure of being part of a touring rock band, especially with a guitarist of Collins’ caliber, was too strong to resist.

Collins was scheduled to “sit in” with us that night at the Golden Nugget. Word spread quickly, and the club was packed with eager Skynyrd fans. Collins emerged from the bathroom, stumbling onto the bandstand, which had a railing in front. He struggled to even put on his guitar – a highly prized 1957 Gibson Les Paul, a testament to his discerning taste in instruments. I had to hold it up for him and fasten his strap.

I took the microphone and announced, “Please welcome Allen Collins to Vidalia!” The crowd erupted in cheers and applause.

Collins grabbed the mic. “You buncha fuckin’ punks,” he slurred. “I’ll kick anyone’s ass in this room right now.”

The audience exchanged bewildered glances, unsure how to react.

Assuming it was some form of bizarre redneck humor, I grabbed the mic and prompted the crowd, “Can y’all say ‘Fuck you, Allen’?”

“Fuck you, Allen!” the audience roared back in unison.

Everyone, including Collins, burst into laughter, the tension momentarily diffused.

We launched into “The Last Time.” During the intro, Collins toppled headfirst over the railing, crashing to the floor face-first. He lay motionless, his feet still propped up on the railing, suspended in a bizarre position. His beautiful Les Paul guitar was broken, the headstock severed from the neck, dangling precariously by the strings. The damage to his prized guitar seemed almost symbolic of his own self-destruction.

I had been trained to never stop playing mid-song, no matter what happened. Stopping during a commotion would only draw more attention, whereas continuing might allow some to remain oblivious. Fearing a larger disturbance, we played on, leaving him lying face-down for what felt like an eternity. Eventually, someone from the audience helped him up.

Collins dusted himself off and wandered over to a table with a birthday cake. He grabbed a piece and hurled it at the birthday girl, who was unaware of the pie-in-the-face tradition. She ducked, he missed again. Her boyfriend, a burly man in a ball cap, looked less than pleased.

Reynolds intervened, grabbing Collins and escorting him out the door to Collins’ white Lincoln Continental. They went to the motel, packed their belongings, and began the two-hour drive back to Jacksonville. We heard nothing from them that night or the next day.

Price and I were driving back to our apartment in Jacksonville. We took a shortcut on State Road 15 through Blackshear, which connects back to U.S. 1. There used to be a stop sign at a particular corner, mounted on a four-by-four post. Now, the post was broken off about two feet above the ground, the stop sign vanished.

Price pointed at the stump and said, “I’ll bet you anything Allen did that.”

“Did what?” I asked.

“Look where the post is whacked off,” he explained. “About bumper height. I bet Allen was driving and ran it over.”

On Monday, we received a call for rehearsal at Collins’ house on Plummer Grant Road. Reynolds opened the garage door to retrieve something from the Continental’s trunk. A massive dent marred the trunk lid.

“How’d that happen?” I inquired. Price glanced at me, eyebrows raised knowingly.

“Allen decided to drive home,” Reynolds replied. “He hit a stop sign on the way back. It broke off, flew over the car, and landed right there.”

Price erupted in laughter. “I told you,” he exclaimed. We both vowed never to get into a car with Collins behind the wheel again.

We entered the rehearsal room. Collins was there, holding a beautiful sunburst Rickenbacker guitar. The plan was for me to co-write songs with him, meaning he would provide the initial idea, and I would flesh it out. He began singing me a song he was working on. I was struck by how much he sounded like Lou Reed, an artist I admired. I mentioned this to Collins. However, Collins apparently loathed Reed, possibly assuming Reed was gay. In response to my comparison, Collins flung the Rickenbacker at me. Fortunately, I managed to catch it mid-air, preventing another guitar from meeting an untimely end against the wall.

After he calmed down, he picked up a Stratocaster, and we began rehearsing “Sweet Home Alabama.” It was only 7 p.m., and he was already too intoxicated to play properly. We were all embarrassed for him. He put down his guitar and announced, “I’ll be right back.” After an hour of waiting, we went inside to find him. He was passed out in a La-Z-Boy recliner, a bottle of Jack Daniels beside him. A thick, black steak was burning in a skillet, filling the kitchen with smoke.

Collins had ample reasons to self-medicate. His band had been decimated in a plane crash, and he himself had suffered a broken neck and nearly lost an arm in the same accident. Adding to his trauma, his wife died three years later. “That’s what destroyed him,” Skynyrd keyboardist Billy Powell (who passed away in 2009) recounted to interviewer Marley Brant. “He dove into a bottle and never came out.” Despite his demons, the brilliance of “Allen Collins guitar” work remained undeniable, even as his personal life spiraled.

Collins was actually a sweet guy

if you caught him sober, which might last for about 20 minutes after waking up. The only other times I witnessed his gentler side was around his daughters, whom he adored, and who clearly adored him in return. This softer side, rarely seen by the outside world, stood in stark contrast to his wild rock star persona.

Ultimately, I could no longer stomach working with him. I had other opportunities to pursue. Hottrax, an Atlanta label that distributed my record “Fuck Everybody,” contacted me, saying the song was generating buzz and suggesting I assemble my own band and bring it to Atlanta for a showcase. That became my focus, and Price joined me. This was late summer 1985.

The events of the night of January 29, 1986, remain shrouded in some uncertainty, but knowing Collins, I have a fairly informed idea of what transpired. Collins was driving his new Ford Thunderbird down Plummer Grant Road with his fiancée, Debra Jean Watts, in the passenger seat. He was not supposed to be driving due to his revoked license. Based on my experiences with him, I speculate that Watts likely urged him to slow down, pull over, and stop acting recklessly. He probably became distracted and swerved. Perhaps she grabbed the steering wheel. Maybe they struggled while traveling at 80 miles per hour.

Regardless of the precise details, the car spun out of control and crashed into a culvert. Both Collins and Watts were ejected through the driver’s side window. Watts tragically died from her injuries.

Collins sustained a broken back, resulting in paralysis from the waist down. Mutual acquaintances suggested that recovery might have been possible had he diligently pursued physical therapy. However, his self-destructive patterns seemed to extend even to his own rehabilitation.

Collins was charged with DUI manslaughter. Initially, he denied driving, but fibers from his shirt, embedded in the driver’s-side door, contradicted his claim. Furthermore, a large bruise on his right side indicated Watts had collided with him during the crash.

Reynolds, who was close to both Collins and his father, Larkin, disputes the police report’s conclusions. Larkin Collins also questioned the official narrative. Reynolds recounts Larkin telling him that both Collins and Watts were ejected from the passenger side, and that Collins exited the vehicle before Watts. This conflicting account highlights the lingering questions surrounding the tragic accident.

For those familiar with Collins, it was clear that entering a vehicle with him, even as a passenger, was risky. Even when not driving, Collins enjoyed terrifying drivers and passengers alike.

“He would stomp his foot down on top of mine [on the gas pedal],” Reynolds explained. “The next thing I knew, we’d be doing 100.” Collins also had a habit of yanking the steering wheel. “He most likely did that while Debra was driving,” Reynolds added. “I was wise to his pranks and could anticipate them, but she wasn’t prepared for that.” This reckless behavior, a consistent thread throughout Collins’ life, ultimately contributed to the devastating tragedy.

Collins eventually pled no contest, claiming amnesia regarding the incident. Considering his severe injuries, Assistant State Attorney Wayne Ellis requested leniency. In addition to probation, the judge mandated that Collins organize and participate in an anti-drunk-driving campaign.

In 1987, Collins and his father decided to reform Lynyrd Skynyrd for a “tribute tour.” The surviving Skynyrd members agreed, and Ronnie Van Zant’s younger brother, Johnny, stepped in as the frontman. Collins served as musical director, selecting Randall Hall, who had been in the Allen Collins Band, as his guitar replacement. This tribute tour, while a musical endeavor, also became a platform for Collins to fulfill his court-ordered anti-drunk-driving campaign.

To fulfill his probation terms, Collins, confined to a wheelchair, appeared before each show to deliver a brief lecture on the devastating consequences of drunk driving. Despite his efforts to raise awareness, Collins’ health deteriorated. He developed chronic pneumonia and passed away in January 1990, marking a somber end to a life marked by both musical brilliance and personal tragedy.

The band, however, persevered. With various replacements filling the roles of deceased members – guitarist Gary Rossington being the sole remaining original member – Lynyrd Skynyrd continues to tour extensively. The Southern rock legacy, born in Jacksonville and shaped by the distinctive “Allen Collins guitar” sound, endures, proving to be a lasting force in music. It’s conceivable that the band’s reunion might not have materialized without Collins’ initial push, a testament to his enduring influence on Lynyrd Skynyrd and the genre itself.

Liked it? Take a second to support The Jitney on Patreon! The Jitney needs gas. Please donate or become a Patron here

[