Willie Nelson and his guitar, Trigger. The names are inseparable, woven into the very fabric of American music. For over five decades, this iconic pairing has graced stages, studios, and hearts around the world. More than just an instrument, Trigger is Willie Nelson’s confidante, his muse, and a tangible extension of his soul. This isn’t just a story about a guitar; it’s a deep dive into the symbiotic relationship between a legendary musician and his equally legendary instrument – Willie Nelson’s guitar, Trigger.

From Nazareth to Nashville: The Genesis of a Legend

The story of Trigger begins not in the smoky honky-tonks of Texas, but in the meticulous workshops of the Martin Guitar factory in Nazareth, Pennsylvania. In 1969, Martin crafted a classical guitar, a model N-20, bearing the serial number 242830. This wasn’t just any guitar; it was a symphony of global craftsmanship. Its Sitka spruce top hailed from the Pacific Northwest, promising a bright and resonant tone. Brazilian rosewood, prized for its rich warmth and complex overtones, formed the back and sides. An ebony fretboard and bridge from Africa offered sleek playability and tonal clarity, while the mahogany neck, sourced from the Amazon basin, provided strength and sustain. Even the brass tuning pegs were imported from Germany, each component carefully selected and assembled.

This Martin N-20, destined to become Willie Nelson’s guitar, was initially intended for a different path. Perhaps it was envisioned in the hands of a classical virtuoso, serenading concert halls with refined melodies. Instead, fate had a different tune in store. This exquisite instrument was shipped to Nashville, the heart of country music, landing in the shop of Shot Jackson, a luthier known for his repair work and sales near the legendary Grand Ole Opry. It was here, in 1969, that a struggling country singer, a man juggling a failing pig farm, a dissolving marriage, and a lackluster record deal, would encounter his destiny. This man was Willie Nelson, and he was about to acquire a new guitar – a guitar that would soon be known as Trigger.

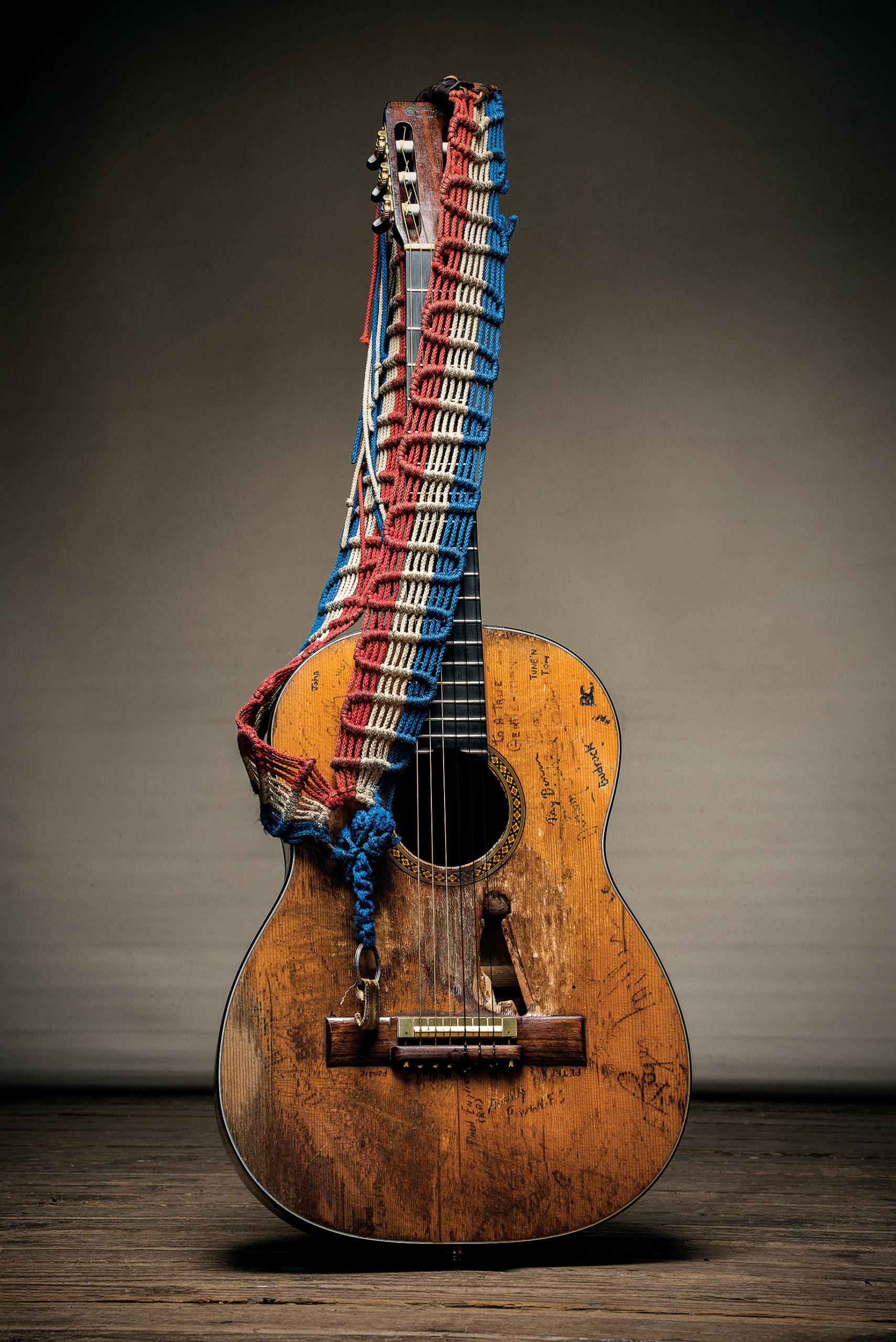

Forty-three years later, after countless performances, recording sessions, and songwriting endeavors, Willie Nelson’s guitar tells a story etched in scars and signatures. Trigger is a testament to a life lived on the road, a life steeped in music and camaraderie. The once pristine instrument now bears the marks of time and tireless use. The frets, worn down by relentless playing, seem barely capable of producing sound. The soundboard is a canvas of scratches, gashes, and autographs carved into the wood, each telling a silent story of encounters and shared moments. Near the bridge, a gaping hole serves as a visual reminder of the instrument’s enduring journey. This isn’t mere damage; it’s a patina of authenticity, a badge of honor earned through decades of dedication to music.

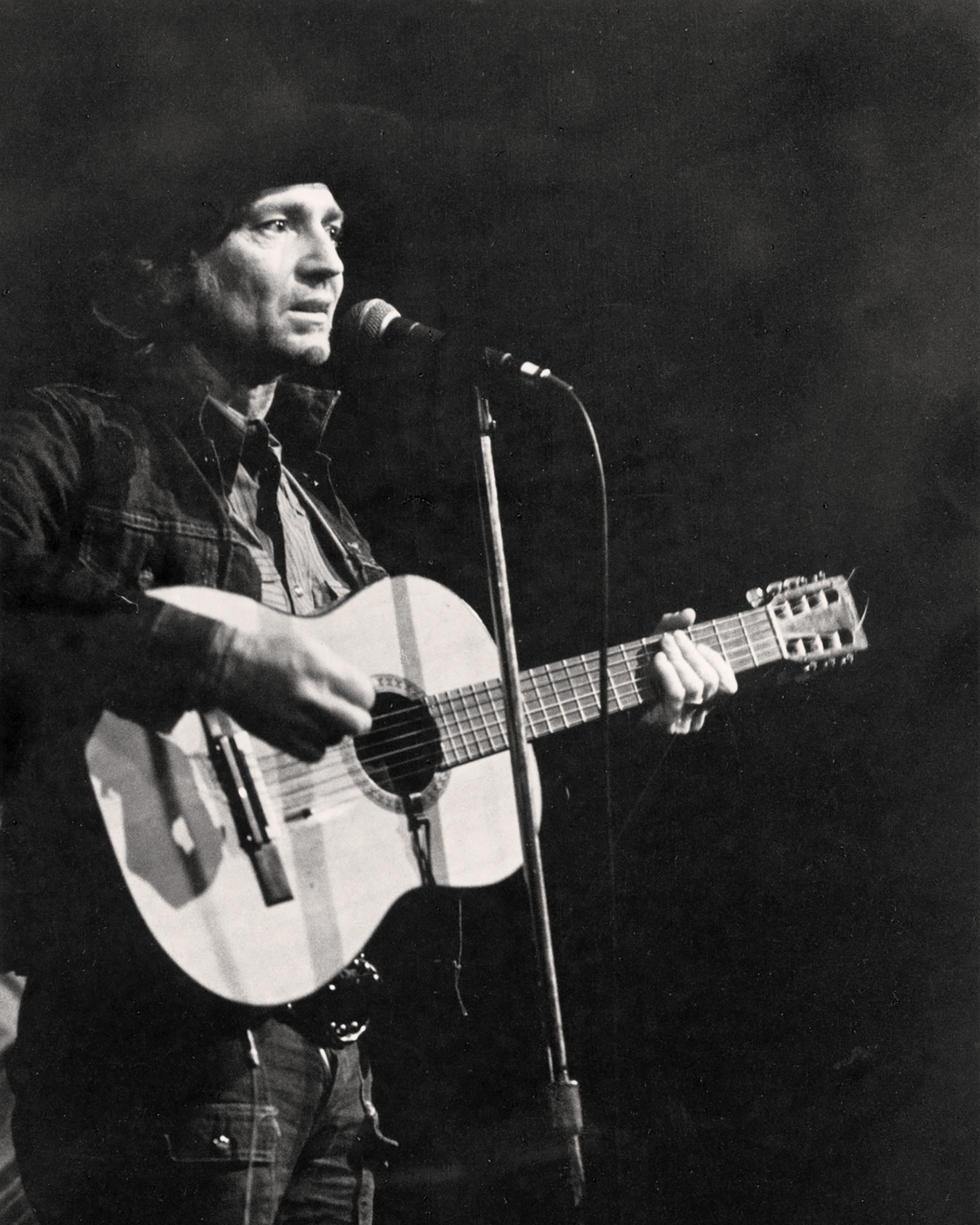

Nelson in his Saloon in Luck in 2012.

Nelson in his Saloon in Luck in 2012.

Trigger and Willie: A Parallel Journey

Most guitars are nameless tools, instruments in the hands of musicians. But Willie Nelson’s guitar is different. This one has a name: Trigger. It possesses a voice, a personality, and a striking resemblance to its owner. Just as Willie’s face is etched with the lines of time and his body carries the weight of experience, Trigger embodies a similar history. Both have weathered storms – Willie through personal trials like divorce, financial hardships with the IRS, the heartbreaking loss of his son Billy, and the passing of close friends like Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash. Physically, Willie has faced his own battles, undergoing carpal tunnel surgery, rotator cuff repair, and a ruptured bicep. The wear and tear of life are mirrored in both man and guitar.

“Trigger’s like me,” Willie Nelson chuckled one cool April morning at his ranch by the Pedernales River. “Old and beat-up.” This simple statement encapsulates the deep connection. Trigger is not just an instrument; it’s a reflection of Willie himself, bearing witness to his journey, absorbing his energy, and resonating with his very essence.

The Voice of Trigger: A Sound Unlike Any Other

Holding Trigger in his lap, Willie Nelson coaxes melodies from the aged wood. The song he chooses is Django Reinhardt’s “Nuages,” a poignant instrumental piece that resonated with the spirit of occupied France during World War II. Willie’s familiarity with Trigger is profound; he knows every contour, every imperfection. His fingers navigate the worn fretboard with practiced ease, effortlessly finding the yearning riff that opens each verse, then gracefully descending to trace the melody. His right hand dances across the strings, plucking single notes and strumming chords with intuitive precision.

He revisits the riff, this time with a quicker tempo, bending a string, shaking the guitar’s battered neck, pushing the instrument to its expressive limits. He returns to the melody, then punctuates it with a sharp chord – da da! – before venturing into improvisational notes that momentarily clash – blonk! – only to gracefully return to the main theme. Each variation, each improvisation, is a testament to the dynamic interplay between Willie and Trigger. The performance culminates in a cascade of sound, a gentle diminuendo like a leaf falling from a tree.

After a reflective sip of coffee, Willie delves into another Django composition, his fingers exploring melodies high on Trigger’s fretboard, weaving a descending riff anchored by a jazz chord. Willie’s hands, large and veined, move with remarkable agility across the strings. For the second verse, his right middle finger transforms into a blur, strumming Spanish-style with hummingbird-like speed. As the song reaches its bridge, Willie unleashes loud, dissonant chords before returning to the familiar verse. The piece concludes with a final, resonant descent and a soft, lingering chord.

Willie Nelson, the multifaceted artist – country songwriter, pop crooner, outlaw icon, marijuana advocate, and farmer’s champion – reveals another facet of his musical persona: that of a truly gifted jazz musician. His playing is characterized by improvisation, emotion, and a willingness to embrace imperfections, always circling back to the core melody, much like a bee drawn to a flower. While some guitarists approach their instruments with meticulous precision, Willie treats Trigger with a different kind of reverence – like a trusted steed, ridden hard and put away wet.

Willie Nelson became the guitarist he is because of this instrument. He has shaped Trigger, and in turn, Trigger has shaped him. Their intertwined history is etched into the wood, resulting in a sound that is instantly recognizable and utterly unique. While most nylon-string guitars possess a similar rich, rounded tone, Trigger stands apart. Its sonic signature is distinctive – low notes that resonate with a deep, earthy thump, and high notes that shimmer with crystalline clarity. Even a few notes are enough to identify the unmistakable sound of Willie Nelson’s guitar on the radio.

Trigger: A Witness to Musical History

No guitar is as cherished or as renowned as Trigger. Its soundboard is a living map of modern music, bearing witness to countless hours of Willie Nelson playing across genres – country, blues, jazz, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, swing, folk, reggae, and pop music from various eras. Trigger was present at the genesis of outlaw country, standing alongside Willie as he defied Nashville conventions and forged his own path. It resonated at the inaugural Farm Aid concert, amplifying the voices of struggling farmers. It was there when Willie serenaded President Jimmy Carter, a symbol of music’s power to transcend political divides. Trigger has shared stages and studios with luminaries like Ray Charles and Bob Dylan, its voice intertwining with theirs. It has hung from Willie’s neck as tens of thousands of fans sang along to anthems like “Whiskey River,” a unifying force in shared musical experience. And it has been cradled in Willie’s lap during moments of solace, offering comfort to friends in times of grief, such as when Willie and Trigger played “Healing Hands of Time” for Darrell and Edith Royal after the loss of their children.

It’s almost impossible to imagine one without the other. Without Willie, there would be no Trigger as we know it. And, with only slight exaggeration, it can be said that without Trigger, there might not be the Willie Nelson we know and love. Willie often remarks that Trigger will likely wear out around the same time he does. Yet, defying the typical slowdown of aging, both Willie and Trigger continue their relentless pace. They performed over 150 shows in the past year and are projected to maintain a similar schedule. New albums will be recorded, new songs will be written, and the music will continue as if time itself is irrelevant.

A close-up of Nelson and Trigger in November 2011.

A close-up of Nelson and Trigger in November 2011.

The Serendipitous Encounter: How Willie Found Trigger

The origin story of Trigger is rooted in a stroke of misfortune, turning into a fortunate twist of fate. Legend has it that Willie Nelson’s journey with his iconic Martin guitar began in 1969 after an unfortunate incident involving his previous instrument. While performing at John T. Floore Country Store in Helotes, Texas, Willie recounts placing his Baldwin acoustic guitar in its case on stage. “A drunk stepped on it,” Willie simply states, marking the end of an era and the beginning of another.

The damaged guitar, a Baldwin 800C Electric Classical, was sent back to Shot Jackson in Nashville for repairs. Ironically, Willie wasn’t particularly attached to this Baldwin guitar, despite its innovative Prismatone piezoelectronic pickup, a groundbreaking technology that allowed acoustic guitarists to be heard alongside a band without being drowned out by microphones. This pickup, paired with a Baldwin C1 amp, was the guitar’s most appealing feature to Willie.

Jackson’s assessment was bleak; the Baldwin guitar was beyond repair. However, he offered a suggestion: he had a Martin N-20 in his shop and could transplant the coveted Prismatone pickup into it. Martin guitars were renowned for their steel-string models, but the N-20 was their venture into the nylon-string market, aiming for the Spanish-style guitar niche. Although Willie was comfortable with nylon-string guitars, purchasing one sight unseen over the phone felt uncertain. “Is it any good?” he inquired. Jackson’s reassuring response, “Well, Martins are known for good guitars,” eased his apprehension. The price was quoted at $750. Willie, recalling a recent horse purchase for the same amount, thought, “That’s pretty cool,” and agreed to the deal, setting in motion the legendary partnership between Willie Nelson and his Martin N-20, soon to be christened Trigger.

Nelson

Nelson

From Stella to Strat: The Guitars Before Trigger

Willie Nelson’s musical journey began long before Trigger, with a humble Stella guitar gifted by his grandparents from Sears when he was six years old. This early instrument, with its high action and unforgiving strings, was a common starting point for aspiring musicians, demanding perseverance and calloused fingertips. As a teenager, Willie progressed to Gibsons, playing lead guitar for Bud Fletcher and the Texans. He honed his skills by emulating the guitar riffs from Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams songs on the radio, absorbing the musical language of his heroes. His musical tastes were broad, encompassing western swing, Tin Pan Alley pop, and the crooning style of Frank Sinatra. In his twenties, he played electric lead guitar with Dave Isbell and the Mission City Playboys, expanding his repertoire and stage presence.

It was during this period that Willie was introduced to the revolutionary sounds of Django Reinhardt, the Belgian Gypsy jazz guitarist who redefined the instrument in 1930s Paris. “When I first heard Django, I realized he was where a lot of things I had learned up to that point had come from, like western swing,” Willie explained. He recognized Django’s influence in the playing of western swing musicians and was captivated by his distinctive guitar tone, a sound he sought to emulate.

Willie’s search for the “right” guitar was a continuous quest. During his time in Houston in the late 1950s, he used an Epiphone steel-string acoustic for teaching guitar lessons and Fender Stratocasters or Telecasters for his nightly honky-tonk gigs. These guitars were functional tools, instruments to deliver songs, but not yet the deeply personal extension he sought. Upon moving to Nashville in 1960, Willie played a variety of guitars – nylon-string, steel-string Gibsons and Martins, and electrics like a Fender Jaguar and a green Epiphone gifted by his wife Shirley. A Fender Jazzmaster even made an appearance in a 1966 live recording. While Willie occasionally played solos, notably on “I Never Cared for You,” these were often replicated from studio versions played by session musicians.

The reality was, Willie was often relegated to a supporting role on his own Nashville recordings. After early songwriting success, his signing with RCA in 1964 steered him towards a country crooner image. Nashville’s studio system at the time typically excluded artists and their touring bands from recording sessions, favoring in-house musicians. Willie found himself making albums filled with lush strings and choral arrangements, a sound that felt increasingly disconnected from his artistic vision. By 1970, discontent was brewing. He felt stifled by the constraints of the Nashville music industry and was undergoing a personal evolution, exploring the poetry of Kahlil Gibran, the prophecies of Edgar Cayce, embracing marijuana, and growing his hair long – outward signs of an inward transformation. He was developing ambitious musical ideas – concept albums, songs exploring spirituality, and introspective narratives – ideas that clashed with the prevailing Nashville formula. Unbeknownst to him, Willie Nelson was on the cusp of becoming a true artist, and all he needed was the spark to ignite his creative fire.

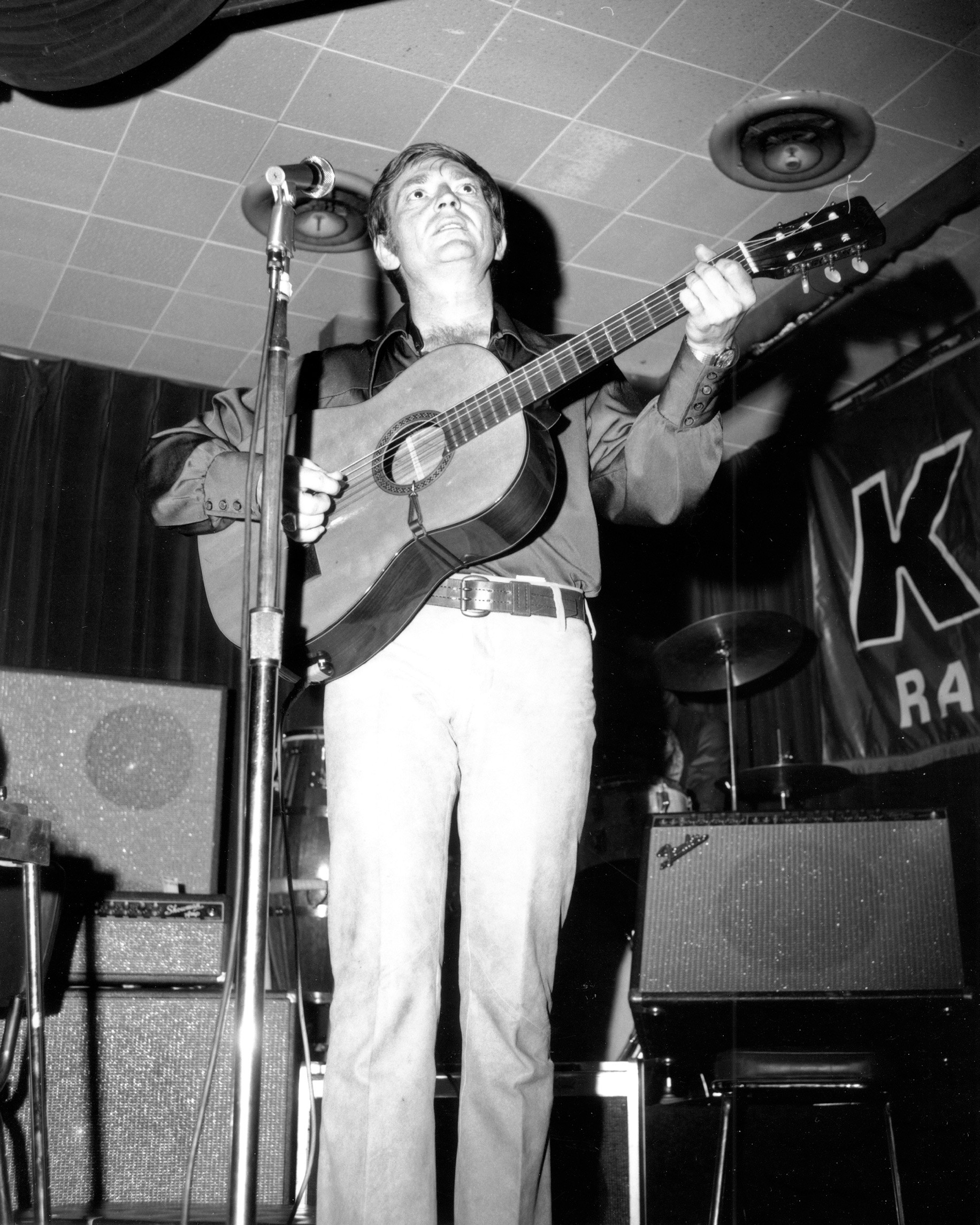

Nelson and Trigger at the Palomino Club in Los Angeles, on May 8, 1970.

Nelson and Trigger at the Palomino Club in Los Angeles, on May 8, 1970.

Nelson and Trigger at the Armadillo World Headquarters, in Austin, in 1972.

Nelson and Trigger at the Armadillo World Headquarters, in Austin, in 1972.

Rebirth in Flames: A Texas Homecoming

The catalyst for Willie’s artistic rebirth arrived in the form of an inferno. In late 1970, his house outside Nashville was destroyed by fire, the cause remaining undetermined. The devastation was comprehensive, consuming clothes, furniture, and master tapes. Yet, from the ashes of tragedy emerged a sense of liberation. The fire symbolically cleansed Willie of his Nashville frustrations, clearing the path for a new beginning. It also provided the perfect impetus to escape Music City and return to his Texas roots. Seizing the opportunity, he relocated to Texas, carrying with him one salvaged treasure from the flames: his new Martin guitar.

Settling near Bandera, Texas, Willie spent months contemplating his future, his Martin guitar his constant companion. He hadn’t yet named the instrument Trigger, but he was developing a profound connection with its sound. “When I found that guitar and amp, I knew that was the sound I was trying to get, that Django sound,” he recalled. Although Django Reinhardt played a steel-string Selmer guitar, Willie perceived its mellow, percussive tone, largely attributed to Django’s use of a tortoiseshell pick, as akin to the sound of a gut-string guitar, much like his Martin.

Upon returning to Nashville briefly, Willie incorporated the Martin into a few recordings. His solo on “I’m a Memory” from the 1971 album Willie Nelson and Family showcased its lyrical quality, hinting at a burgeoning artistic force.

Later that year, at a music industry gathering at Harlan Howard’s home, Willie’s late-night performance with his Martin captivated an unexpected audience. As the party dwindled, Willie, perched on a stool, played songs from Phases and Stages, a concept album exploring the complexities of divorce. The intimate setting amplified the raw emotion in his spare, poignant songs. Among the captivated listeners was Jerry Wexler, the legendary producer who had launched the careers of soul and R&B icons. Wexler, then establishing a country division at Atlantic Records, was profoundly moved and offered Willie a record deal, promising the creative freedom he craved.

Willie signed with Atlantic, marking a pivotal turning point. He then made an even more significant move, leaving Nashville permanently and returning to Texas, to a ranch west of Austin. He was home. His first Atlantic album, Shotgun Willie, announced the arrival of a new Willie Nelson, sonically defined by his Martin guitar. The album’s title track immediately showcased Trigger’s voice, with Willie’s guitar riffs weaving through the bluesy groove. “Shotgun Willie” and “Whiskey River” became anthems of this transformation, with Trigger leading the charge, guiding the songs with its distinctive sound. “Those two songs are the ones where I really started changing,” Willie reflected, “where I switched into blues more, rock ’n’ roll blues stuff.” The guitar was not just an instrument; it was a catalyst for his artistic evolution.

The Martin, even in its relative youth, began to show signs of wear. In 1974, Willie Nelson debuted on Austin City Limits. Looking back at that performance, both Willie and his guitar appear remarkably young. His beard retained its red hue, and the guitar’s finish was still bright yellow, but a small hole had already emerged near the bridge, a testament to Willie’s forceful playing style. “When I saw the hole coming in there, I didn’t panic or anything,” he said, recalling guitars from his youth that already bore similar marks of use. On “Whiskey River,” his fingers can be seen curling around the nascent hole as he played. Plugged into the Baldwin amp, the guitar’s sound was clear and grounded, and Willie’s playing, while rooted in country traditions, hinted at the improvisational explorations to come.

The Martin empowered Willie, fueling his creative ambitions. He recorded Phases and Stages and then Red Headed Stranger, a spare, emotionally resonant masterpiece where man and instrument seemed inextricably linked, their voices blending into a raw, quivering vibrato. The listener could almost feel Willie’s fingers pressing and pulling the strings, hear the air in the recording space, and sense the deliberate silences in the music.

In 1978, nearly a decade after acquiring the Martin, Willie Nelson released Stardust, the album that would catapult him to mainstream superstardom and solidify his artistic vision. Shotgun Willie and Red Headed Stranger had established his unique brand of country music; Stardust transcended genre, representing a synthesis of Tin Pan Alley, jazz, country, and pop, a musical landscape he and his guitar had been charting for years. Willie’s playing on Stardust was both elegant and powerful, with a percussive attack that underscored the emotional depth of the material. His vocals, reminiscent of Sinatra’s phrasing, were matched by Trigger’s expressive voice.

Stardust was Willie Nelson’s most ambitious musical statement to date, driven by artistic vision rather than commercial aspirations. Yet, paradoxically, it became his biggest commercial success, selling over five million copies and cementing his status as a musical icon.

Mark Erlewine and Willie Nelson

Mark Erlewine and Willie Nelson

Sustaining a Legend: The Care of Trigger

As Willie Nelson’s sound became inextricably linked to his Martin guitar, ensuring its upkeep became paramount. This responsibility fell to Poodie Locke, Willie’s trusted stage manager. In the mid-1970s, Poodie sought out Mark Erlewine, a young Austin luthier with a growing reputation. After an initial meeting at the Austin Opry House bar, Willie’s instructions to Erlewine were simple yet profound: “Just keep my guitar going—as long as it’s working, I’ll be working.”

Erlewine’s initial tasks involved cleaning and sealing the raw spruce around the growing hole in the soundboard. “Spruce is a very soft wood,” Erlewine explained, “and everything that gets in—sweat, beer—affects it.” The guitar already bore its first autographs, etched in by Leon Russell with a knife and by Johnny Bush with a ballpoint pen, marking the beginning of Trigger’s unique visual history.

Poodie became Erlewine’s regular client, bringing Trigger in for maintenance during tour breaks. The expanding hole was a primary concern, exacerbated by Willie’s forceful playing. The wood surrounding it was thinning precariously. “It was so thin,” Erlewine recalled, “you could have accidentally put your finger through it.” To reinforce the structure, Erlewine installed mahogany braces beneath the soundboard. Willie’s expansive playing style, reaching from the bridge to beyond the soundhole, demanded extensive cleaning. Erlewine used cotton diapers and naphtha solvent to remove accumulated sweat, skin, and grime before applying lacquer and buffing the finish. The fretboard received similar attention, cleaned with steel wool and treated with lemon oil.

With each visit, Trigger returned with more autographs, a growing tapestry of musical camaraderie. Famous musicians like Roger Miller, Johnny Cash, and Kris Kristofferson added their names, alongside members of Willie’s band and crew: Paul English, Poodie himself, Budrock Prewitt, and Tune’n Tom (Tom Hawkins), Trigger’s dedicated road caretaker responsible for string changes and tuning. Some signatures, hastily applied with Magic Marker or Sharpie, faded quickly under the rigors of nightly performances. Others, scratched with ballpoint pens, proved too shallow and also succumbed to time and wear. Eventually, the sheer volume of signatures blurred into an indistinguishable collection, a testament to Trigger’s many encounters.

Willie and his band were constantly on tour, spending up to six months a year on the road. His playing style became increasingly idiosyncratic, marked by improvisational solos and string bending techniques that pushed the limits of the instrument. He blended rhythm and lead playing, strumming chords while simultaneously weaving single-note lines, gypsy chords, and arpeggiated solos, all infused with bluesy riffs and intense string bends.

This relentless playing took its toll. Willie’s forceful attack continued to erode the soundboard, exposing the internal braces. Erlewine had to reinforce these with additional mahogany braces and spruce cleats. Eventually, the hole stabilized, ceasing to expand further. Another issue arose when the guitar was dropped, damaging the input jack. This damage was remedied with a metal plate, and the jack was relocated to the guitar’s base. Even the Baldwin amp, a crucial part of Willie’s signature sound, required constant maintenance, relying on cannibalized parts from fan donations to keep it functioning.

Even Willie’s offstage habits contributed to Trigger’s wear and tear. Erlewine frequently replaced the tuning pegs, particularly the D-string peg, due to breakage. Poodie explained Willie’s nervous habit of fidgeting with the D-string peg during shows, constantly turning it up and down, damaging the gears. Unaware of this unconscious habit, Willie continued, necessitating peg replacements every few years.

In 1989, while touring in Southern California, Poodie rushed Trigger to Rick Turner’s shop in Los Angeles. The bridge had split and broken off, a critical failure with a show scheduled the next day. “We gotta get it fixed,” Poodie implored Turner, emphasizing Trigger’s irreplaceable role: “When the guitar can’t go on, he won’t go on.” Turner, facing a tight 24-hour deadline, managed to rebuild, glue, and set a new bridge, a process that typically requires at least 48 hours. Trigger was back in Willie’s hands, ready for the next performance.

Nelson and Trigger play a show in Austin in 1984.

Nelson and Trigger play a show in Austin in 1984.

Nelson and Trigger at Pedernales Recording Studio making the album Hill Country Christmas, in 1997.

Nelson and Trigger at Pedernales Recording Studio making the album Hill Country Christmas, in 1997.

Trigger’s Enduring Spirit: Surviving Hard Times

Willie Nelson’s freewheeling lifestyle faced a stark reckoning in late 1990 when years of unpaid taxes culminated in a raid by federal agents on his Pedernales ranch. Everything of value was seized, a devastating blow. Yet, amidst the chaos, one invaluable possession remained untouched: Trigger. The guitar was safely stowed on Willie’s tour bus, parked just beyond the reach of the authorities. Willie, in Hawaii during the raid, upon learning of Trigger’s safety, requested his daughter Lana to send it to him, a gesture of both practicality and emotional reassurance. She retrieved the guitar and ensured its safe return to her father.

By this time, Willie had christened his Martin with a name that resonated with its spirit: Trigger. After two decades of unwavering service, the guitar had earned its moniker. Willie’s life journey – from Abbott, Texas, to Nashville songwriter, outlaw country icon, and pop superstar, culminating in a confrontation with the federal government – had been epic, almost biblical in scale. Such a life demanded more than just a guitar; it needed a companion, a symbol. When asked about the name, Willie’s explanation was characteristically simple: “Roy Rogers had a horse named Trigger. I figured, this is my horse!”

And like Roy Rogers and his Trigger, Willie rode his musical “horse” relentlessly, determined to overcome his financial debts and reclaim his life. He recorded nine albums between 1992 and 1996, many of which centered on Trigger’s voice, including the introspective Spirit (1996), still a personal favorite. He toured relentlessly, his playing sometimes reaching a frenetic intensity, as if channeling John Coltrane through Django Reinhardt’s spirit. He would turn to face his amp, coaxing feedback, slashing at the strings, always dictating his own tempo. His band, accustomed to his improvisational style, would follow his lead. “I just start playing, and all the musicians wait to see what I’m doing before they jump in there. Because at that point, I’m not sure what I’m gonna do.” The stark contrast was evident when Willie occasionally switched to a Stratocaster for blues numbers; his playing, while technically proficient, lacked the distinctive voice and soulfulness that Trigger provided. Willie needed Trigger, and Trigger, it seemed, needed Willie.

Erlewine continued to provide Trigger’s bi-annual checkups as the guitar entered its middle age. The frets, particularly in the first few positions, were severely worn, not just with the typical divots under the strings, but flattened across their entire width, evidence of Willie’s extreme string bending. Flat frets caused buzzing and a diminished tone, requiring even greater force to produce a clear sound. Erlewine suggested a refret, but Willie declined. “I like the way it’s sounding all right,” he insisted. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

In recent decades, Willie Nelson has leveraged his legendary status to pursue diverse musical projects, recording albums he had long envisioned and collaborating with artists he admired. He created an instrumental album celebrating Django Reinhardt, a children’s album centered around Trigger, and even a collaboration with Wynton Marsalis, blending blues and jazz. He revisited his western swing roots with Asleep at the Wheel, bringing his musical journey full circle. Throughout these varied endeavors, Trigger remained the constant, accumulating, by Willie’s estimate, over a million minutes of playing time.

Erlewine’s semi-annual inspections of Trigger became a ritual. He would oil the bridge, clean the fretboard, now deeply eroded between the frets, and meticulously apply lacquer to the soundboard. The area above the soundhole, bearing fifty coats of lacquer accumulated over 35 years, revealed a mottled surface, with darker areas stained by ingrained dirt and skin, and lighter patches where Willie’s playing had worn deep into the spruce. He carefully treated the gouges running parallel to the strings, evidence of Willie’s forceful picking. “To go in and pull on the strings like that,” Erlewine observed, “is more of an unschooled, gypsy way of doing things.”

He examined the wear along the guitar’s upper curve, where Willie’s arm had rubbed for decades, and the scratches near the soundhole caused by the strap clip. He paid particular attention to the remaining legible signatures, and in the right light, could discern faint impressions of others, names fading into the wood like memories.

Finally, he would peer into Trigger’s gaping hole. Willie, in his Zen-like acceptance, insisted the hole was beneficial. “I always thought it enhanced the sound,” he claimed. And he might be right. Luthiers have long experimented with soundhole variations, and some Hawaiian guitar makers even incorporate two soundholes in their designs. The thinning spruce around the hole, according to Dick Boak, a Martin Guitars designer and archivist, could indeed improve the sound. “As you scratch away at the top, the diminished thickness of the membrane will most likely make the guitar sound better.”

Despite its extensive wear and tear, Erlewine consistently found Trigger to be in remarkably good condition, with the exception of the frets. “There are certain notes that are just pffft!” he admitted. While those around Willie acknowledged the issue, the consensus was to leave it unchanged. Erlewine eventually conceded, recognizing that Trigger’s worn frets were simply part of its character, and Willie’s playing style had adapted to them. The worn frets, in fact, seemed to compel Willie to play with even greater force, vibrato, and string bending, adding to Trigger’s unique voice.

Despite its history in the hands of a band known for its wild lifestyle, Trigger had avoided major structural damage. It had no cracks, its headstock remained intact, and its sides and back were relatively sound. While Willie sometimes appeared nonchalant with Trigger onstage, even lifting it high by the neck, he was fiercely protective of it, physically intervening on at least two occasions to retrieve it from drunken musicians.

The only significant alteration Willie permitted was around 2008, when he sought to modify the strap attachment. For decades, he had used a mariachi-style strap looped around his neck and clipped to the soundhole. However, years of this had created a painful knot on his neck. He opted for a conventional strap, requiring a button to be installed on the neck heel. Erlewine complied, but the change was short-lived. “It changed the whole balance of the guitar,” Tom Hawkins explained. Willie reverted to his original strap configuration after just one day.

After each checkup, Erlewine would restring Trigger, strum it, and marvel anew at its rich tone. Like a Stradivarius violin, guitars tend to improve with age. The wood matures, and the tone becomes more vibrant. “New guitars have to have time to open up,” Erlewine explained. “The wood has to vibrate, it has to move, to bring the sound out. Willie plays so much, it’s brought out the tone of the guitar.”

Over the years, Willie’s crew had tried to persuade him to use another guitar, or at least give Trigger a break. In the mid-1990s, Poodie located a pristine 1968 N-20. Willie tried it, thanked him, and returned to Trigger. In 1998, Martin Guitars created a replica N-20, the Limited Edition Signature N-20WN, in Willie’s honor. Willie tested one, expressed his gratitude, and put it back in its case. His loyalty to Trigger was unwavering, his aversion to change legendary. He simply wouldn’t play another guitar. “Every guitar has its own feel and sound,” Willie explained. “The Trigger replicas are nice guitars, but anyone who has played this guitar can tell you immediately that there’s a different feel.”

The intangible essence of Trigger, the connection forged over decades of shared music, was impossible to replicate. “I don’t know why,” Willie admitted, unable to articulate the magic that bound him to his irreplaceable instrument.

Willie Nelson

Willie Nelson

“Nuages” and Beyond: Trigger in the Studio

In June, Willie Nelson and his band convened at his Pedernales studio, a sanctuary from the road and the outside world, a place to create and to find solace. This studio, witness to both artistic masterpieces and commercial hits, was a space where Willie could escape, play, and honor the memory of departed friends.

Willie, dressed in his characteristic black jeans, t-shirt, running shoes, and white socks, sat near a window overlooking the Hill Country, Trigger resting in his lap. An ashtray, cowboy hat, and cellphone sat on a nearby table. The band – harmonica player Mickey Raphael, drummer Billy English, bassist Kevin Smith, and Willie’s sister Bobbie Nelson on piano – were positioned in separate rooms or isolation booths.

A cable connected Trigger to the battered Baldwin amp, its original 1968 frame housing mostly replaced internal components. The Supersound tone buttons, though faded, still retained their vibrant colors, except for the missing purple one, a casualty of time.

While recent Willie Nelson albums had often been ensemble-driven, this session aimed for a more intimate recording style, reminiscent of his earlier work. The repertoire included original songs and standards like “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” “Twilight Time,” and “Nuages.”

Decades after leaving Nashville, Willie maintained the efficient studio habits he had learned there, approaching recording with a matter-of-fact professionalism, moving swiftly from take to take, song to song, minimizing second-guessing.

The band worked on “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So,” a classic ballad. Willie gently guided drummer Billy English towards a lighter, more nuanced drum pattern. They ran through sections, refined the arrangement, and then recorded full takes. As Willie sang, Trigger responded, its voice weaving in and out of the vocal melody.

“I wish I didn’t love you so.” (Breeng! Bree!)

“My love for you should have faded long ago.” (Da-da-da!)

Willie’s solo began with a bluesy phrase, ascended quickly, then settled around the melody, a conversation between voice and instrument.

“Okay,” Willie announced, “let’s do it again.” The next take, and subsequent takes, explored different nuances, with Trigger’s solos evolving, sometimes more inspired, sometimes more understated, always in dialogue with the song.

As afternoon light streamed through the window, illuminating Trigger’s worn surface and the lines etched on Willie’s face, he called for another take, this time with a fade-out ending. He experimented with bluesy riffs in the verse, emphasized chords in the chorus, and unleashed flurries of notes before returning to the melody, his body language mirroring the music, heels lifting from the floor, Trigger rising and falling in his lap. His vocals, imbued with characteristic vibrato, stretched and lingered. The second solo soared higher, the notes cascading like rain.

“Master your instrument,” jazz legend Charlie Parker advised. “Master the music and then forget all that and just play.” Willie’s playing embodied this spirit, particularly in his solos, racing ahead of the beat, then falling back, improvising runs that felt both familiar and entirely new, moments of pure musical creation.

After a few more songs, Willie called for “Nuages.” He played the melody, then passed the solo to Bobbie on piano, listening intently as she played. They recorded several takes, and on the final one, Willie closed his eyes during Bobbie’s solo, his fingers moving lightly on Trigger’s neck, as if keeping them ready. As Bobbie’s solo concluded, Willie opened his eyes, placed his hands on Trigger, and together, man and guitar, began to play, the enduring partnership continuing to create musical magic.