In the summer of 2000, a journey through Israel’s battlefields with Michael Kovner, son of Zionist leaders Abba and Vitka Kovner, became a profound exploration of the nation’s history and spirit. Kovner, a former member of Sayaret Matkal, offered firsthand insights into Israel’s wars, revealing sites from the 1948 War of Independence to the Yom Kippur War. Initially envisioning a War and Peace-esque chronicle of Israel, the experience, particularly revisiting the Yom Kippur War battlefields, took on a deeper, more somber tone.

Kovner recounted tales of resilience and strategic brilliance from past conflicts, including his father’s role in holding Negba during the 1948 war and the innovative use of an ancient Roman road in the 1956 Suez Crisis. The swift victory of the 1967 Six-Day War was also part of his narrative. However, the atmosphere shifted dramatically when they reached the sites of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Kovner’s personal experience of the Yom Kippur War began in New York, where, upon hearing of the surprise attack, he joined hundreds of Israelis at JFK airport, all determined to return and defend their homeland. While this mass mobilization seemed inspiring—a generation returning to protect a nation that could have saved millions just decades prior—Kovner’s perspective was tinged with the war’s heavy aftermath.

From an external viewpoint, the Yom Kippur War might appear as a swift victory, paving the way for peace with Egypt. Yet, for Israelis, it was a rude awakening. Shattering the illusion of invincibility established after 1967, the war instilled a deep, lingering sense of vulnerability and loss. This shift in national mood, a “mournful funk,” is powerfully captured in Matti Friedman’s Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai. The book delves into Leonard Cohen’s 1973 singing tour during the war, illuminating the conflict’s profound psychological impact on Israel, far beyond the battlefield statistics.

Friedman’s work portrays Cohen, then grappling with artistic stagnation in Hydra, seeking a creative and spiritual resurgence amidst the war. Cohen, rooted in an Orthodox Jewish background and Montreal’s Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, felt an undeniable pull to Israel during this crisis, mirroring the impulse of many others who flocked to defend their nation. His initial intention to volunteer on a kibbutz seemed secondary to a deeper, almost instinctive calling.

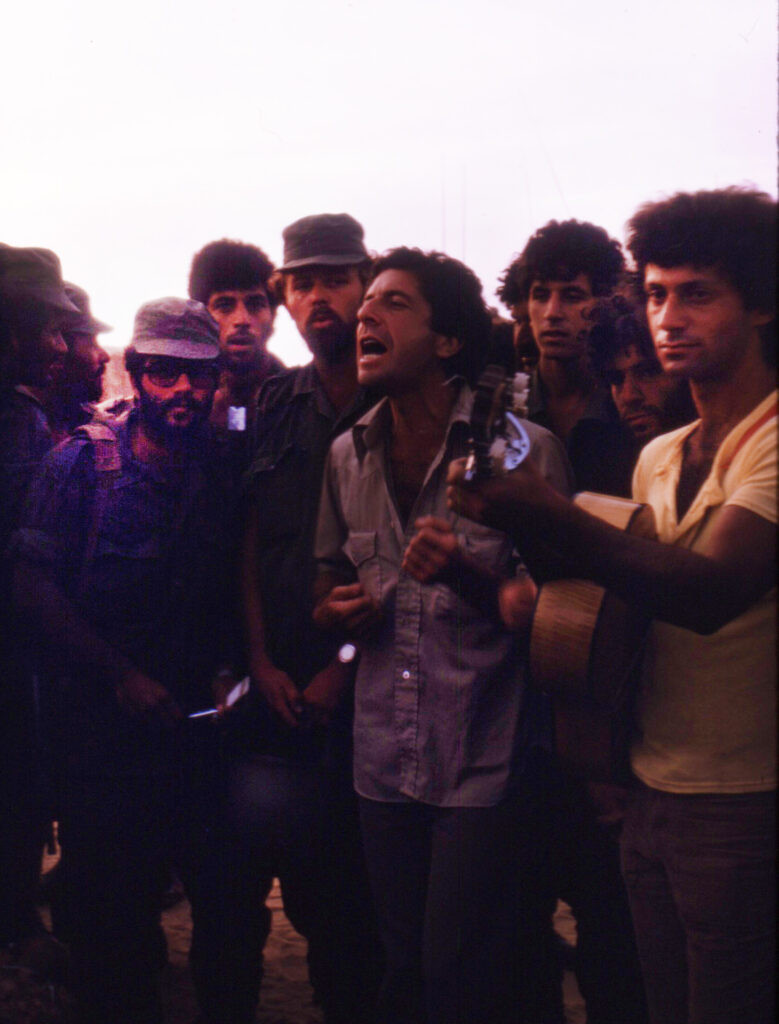

Arriving in Tel Aviv, Cohen connected with local musicians, including Matti Caspi, and spontaneously began performing for soldiers. These impromptu concerts, undocumented at the time, are reconstructed by Friedman through accounts from soldiers and fellow performers, painting a picture of Cohen’s journey across military bases in Israel, the Golan Heights, and even into “Africa”—the perilous Egyptian side of the Suez Canal.

This was far from a typical morale-boosting tour. Cohen shared the soldiers’ harsh conditions, sleeping in borrowed beds, tents, or under open skies, amidst the dangers of war. For soldiers unfamiliar with Cohen, his presence was an anomaly, a strange yet welcome distraction. For those who knew his music, it was another surreal element of an already disorienting time. These performances resonated deeply, leaving a lasting impact on both the soldiers and Cohen himself. The raw reality of war, the camaraderie, the fear, and the stark landscape of Israel unlocked something within him. During this period, he began journaling, capturing images and phrases that would evolve into new lyrics. “Lover Lover Lover,” his first song in years, emerged from this crucible, a testament to his revitalized creativity:

I asked my father

I said “Father change my name

The one I’m using now it’s covered up

With fear and filth and cowardice and shame.”

Cohen’s music, always imbued with biblical echoes, took on a more explicitly liturgical quality in the following decades. Songs like “Hallelujah,” “Tower of Song,” and “Who By Fire”—a direct, poignant reflection on the Unetanneh Tokef prayer—became iconic. These works, much like the minor key progressions and heartfelt melodies often found in what could be termed Jewish Chords Guitar music, explored themes of faith, mortality, and redemption with profound depth. While not explicitly composing in a genre defined as “Jewish chords guitar,” Cohen’s music resonated with a sensibility that echoed traditional Jewish musical modes and emotional expression.

Friedman’s insightful account is enriched by Cohen’s wartime diary, fragments of an unfinished war novel, and evocative photographs by soldier Isaac. These images capture Cohen performing for intimate groups of soldiers, including a notable appearance before Ariel Sharon. However, the book’s true focus is on the soldiers themselves—their weary faces, their rapt attention. Their stories of deployment, survival, and loss form the emotional core of Friedman’s narrative, explaining why the Yom Kippur War remains a pivotal, deeply felt event in Israeli consciousness, comparable in impact to the foundational wars of 1948 and 1967. Cohen, in this context, acts as a unifying thread, his music weaving through the experiences of these IDF members.

Cohen departed Israel as peace negotiations began, distancing himself from the political aftermath. He rarely discussed his wartime experiences publicly, perhaps wary of being pigeonholed as a Jewish artist in a mainstream music industry. Yet, for those who witnessed his Sinai performances, his commitment was undeniable. As Friedman notes, Cohen’s enduring status in Israeli culture transcends mere Jewish identity. It is rooted in the collective memory of his presence during a moment of national crisis, offering solace and connection through his music—music that, in its emotional depth and thematic resonance, shares a spiritual kinship with the evocative qualities sometimes associated with Jewish chords guitar and Jewish musical traditions. His melodies, though universally resonant, carried a particular weight and meaning in that specific time and place, much like the enduring power of music deeply rooted in cultural and spiritual heritage.