Joni Mitchell’s music captivates with its constant sense of surprise and inventive spirit, and at the heart of this sonic adventure lies her guitar. Melodies and harmonies unfold in ways that defy pop conventions, creating a soundscape that is both familiar and strikingly original. Her approach to the guitar transcends typical playing styles; the treble strings evoke a cool-jazz horn section, while the bass strings snap syncopations reminiscent of a snare drum. Chords ring out in clusters that seem impossible from a standard six-string. Layered upon this instrumental innovation is her voice, further extending the harmonic richness and coloring melodies with poetic and insightful lyrics.

Even with her status as one of the most revered songwriters and a significant influence across generations of musicians, the creative processes driving Joni Mitchell’s music have remained largely enigmatic. For guitarists captivated by her playing on albums like Court and Spark or Hejira, the quest to understand her sound often hits a wall. Her techniques, from her unique tunings to her strumming hand, are far removed from conventional guitar approaches. The limited published resources documenting her 30-year guitar journey consist of just four songbooks transcribed by Joel Bernstein, her long-time guitar tech and archivist, revealing tunings and chord shapes. This is a small glimpse into a career spanning 17 albums, each marking a departure from the last. Remarkably, Mitchell herself relies on Bernstein’s extensive knowledge of her work, often needing his help to relearn older songs due to her constant exploration of new tunings and infrequent revisiting of past repertoire.

Following her 1996 Grammy win for Best Pop Album for Turbulent Indigo, a landmark album that brought her acoustic guitar back to the forefront, Joni Mitchell offered a rare, in-depth look into her craft as a guitarist and composer in an interview.

“There’s a certain kind of restlessness that not many artists are cursed or blessed with,” Mitchell explained. “Craving change, craving growth, always seeing room for improvement in your work.” This statement encapsulates the essence of her music: a continuous process of invention rather than a series of finished pieces.

The Unconventional Sound of Her Guitar

The sound of her guitar is instantly recognizable, yet difficult to categorize. It’s a sound that defies easy imitation, partly because it’s so deeply intertwined with her personal approach and her constant experimentation. Listeners often describe her guitar as sounding “not really like a guitar,” and this is precisely the point. She pushes the instrument beyond its traditional boundaries, using it as a canvas for harmonic exploration and rhythmic innovation. The treble strings, in her hands, sing with a clarity and articulation that recalls the precision of a jazz horn section, while the bass lines are percussive and syncopated, adding a rhythmic drive that is both subtle and powerful. The chords she creates often feel expansive and complex, defying the typical shapes and voicings found in standard guitar playing. This unique sonic landscape is a key element of her artistic identity, setting her apart from her contemporaries and inspiring countless musicians.

For those seeking to unravel the mystery of her guitar playing, traditional resources offer limited assistance. Music stores and conventional guitar instruction methods simply don’t address the intricacies of her style. The published songbooks, while valuable, only scratch the surface of her vast and evolving techniques. Even Joni Mitchell herself acknowledges the depth of her own exploration, often relying on Joel Bernstein’s encyclopedic knowledge to navigate her extensive catalog of tunings and songs. This reliance highlights the intensely personal and constantly evolving nature of her guitar journey. Her sound is not a fixed style to be learned, but rather a continuous process of discovery, making it all the more captivating and elusive.

Early Influences and the Path to Originality

Joni Mitchell’s guitar journey began like many young musicians of the 1960s, but she quickly diverged onto a unique path. Her initial foray into guitar playing was guided by Pete Seeger’s instructional book, The Folksinger’s Guitar Guide. She was particularly drawn to the fingerpicking style of Elizabeth Cotten, a legendary blues and folk guitarist known for her unique alternating bass technique. Mitchell attempted to emulate Cotten’s style, characterized by the thumb alternating between the sixth and fifth strings to create a rhythmic foundation. However, she found herself unable to replicate this technique precisely. “I couldn’t do that, so I ended up playing mostly the sixth string, but banging it into the fifth string,” she recalled.

This initial “failure” to master Cotten’s technique became a pivotal moment in the development of her guitar style. Instead of becoming discouraged, Mitchell embraced her own interpretation, transforming a technical limitation into a source of originality. “Elizabeth Cotten definitely is an influence; it’s me not being able to play like her. If I could have I would have, but it’s a good thing I couldn’t, because it came out original.” This anecdote reveals a crucial aspect of her creative process: embracing imperfections and allowing them to shape her unique voice. By not being able to conform to a traditional style, she inadvertently stumbled upon the beginnings of her own groundbreaking approach to the guitar. This early experience instilled in her the value of experimentation and the potential for originality to emerge from unexpected places.

The World of Alternate Tunings: Her Guitar’s Foundation

Alongside her departure from standard folk fingerpicking, Joni Mitchell also broke away from standard guitar tuning. Remarkably, only two of her songs, “Tin Angel” and “Urge for Going,” are in standard tuning. Her exploration into alternate tunings became a cornerstone of her guitar sound and songwriting process. “In the beginning, I built the repertoire of the open major tunings that the old blues guys came up with,” she explained. She started with the foundational open tunings used by blues and folk musicians, including D modal (D A D G B D), famously used by Neil Young, and open G (D G D G B D), with the fifth string removed, a tuning favored by Keith Richards. She also explored open D (D A D F# A D).

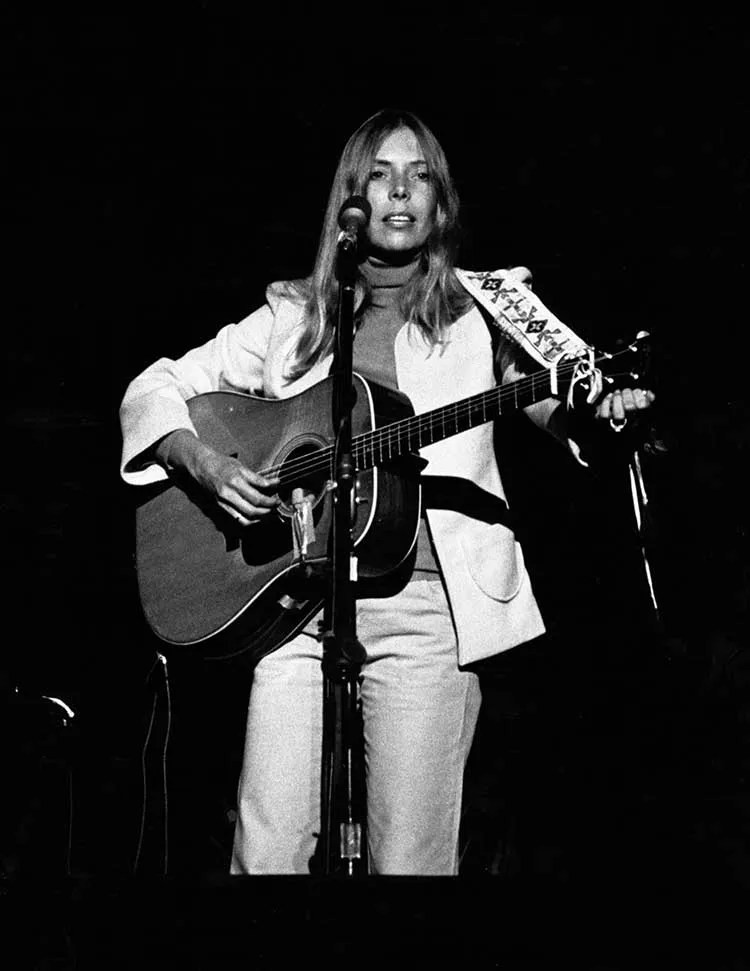

Joni Mitchell onstage with acoustic guitar

Joni Mitchell onstage with acoustic guitar

These open tunings provided a starting point, but Mitchell quickly moved beyond them, seeking more complex and nuanced sounds. “Then going between them I started to get more ‘modern’ chords, for lack of a better word.” As she began writing songs in the mid-1960s, these tunings became inextricably linked to her compositional process. The tunings were not merely a technical choice but an integral part of her songwriting, influencing the melodies, harmonies, and overall emotional tone of her music. Her guitar, therefore, became a vehicle for exploring new harmonic territories, with alternate tunings serving as the gateway to uncharted sonic landscapes.

On her first three albums, Joni Mitchell (1968), Clouds (1969), and Ladies of the Canyon (1970), a blend of conventional open tunings and more innovative tunings began to emerge. Songs like “Both Sides, Now” and “Big Yellow Taxi” utilized open E (E B E G# B E), essentially open D raised a whole step, while “The Circle Game” and “Marcie” were in open G. However, it was the more adventurous tunings, such as C G D F C E for “Sisotowbell Lane,” that truly captivated her. These tunings, with their complex chords achievable through simple fingerings, became the bedrock of her guitar style from the early 1970s onwards. This period marked a significant shift towards more intricate harmonic textures and a further departure from traditional folk idioms.

Harmonic Innovation: Beyond Folk and Jazz

Joni Mitchell’s exploration of alternate tunings led her to discover a unique harmonic language that transcends genre boundaries. She described pure major chords as evoking “pure well-being,” but recognized that “anybody’s life at this time has pure majors in it, given, but there’s an element of tragedy. No matter what your disposition is, we are air breathers, and the rain forests coming down at the rate they are… there’s just so much insanity afoot. We live in a dissonant world.” This awareness of the complexities of life informed her harmonic choices, leading her to incorporate dissonance into her music. While “dissonances” might suggest harsh sounds, the “modern chords” she found in alternate tunings possess a subtle softness, with consonance and dissonance interplaying gently.

Categorizing these sounds is challenging, but Mitchell is clear about one thing: they are far removed from folk music. “It’s closer to Debussy and to classical composition, and it has its own harmonic movement which doesn’t belong to any camp,” she asserted. While some might perceive jazz influences due to the harmonic breadth, she clarifies, “It’s not jazz, like people like to think. It has in common with jazz that the harmony is very wide, but there are laws to jazz chordal movement, and this is outside those laws for the most part.” Her guitar harmony, therefore, occupies a unique space, drawing inspiration from classical and jazz but ultimately forging its own distinctive path.

Mitchell’s process of discovering these expansive harmonies is intuitive and experimental. “You’re twiddling and you find the tuning. Now the left hand has to learn where the chords are, because it’s a whole new ballpark, right? So you’re groping around, looking for where the chords are, using very simple shapes.” She starts by exploring simple shapes within a new tuning, often finding initial chords readily available: “Put it in a tuning and you’ve got four chords immediately—open, barre five, barre seven, and you higher octave, like half fingering on the 12th. Then you’ve got to find where the interesting colors are—that’s the exciting part.” This process of tactile exploration and discovery is central to her approach to her guitar, emphasizing intuition and the serendipity of finding unexpected sounds.

The Philosophy of Experimentation and Growth

Mitchell’s creative philosophy is deeply rooted in experimentation and a constant pursuit of growth. She described how tunings can emerge from various sources: “Sometimes I’ll tune to some piece of music and find [an open tuning] that way, sometimes I just find one going from one to another, and sometimes I’ll tune to the environment. Like ‘The Magdalene Laundries’ [from Turbulent Indigo]: I tuned to the day in a certain place, taking the pitch of birdsongs and the general frequency sitting on a rock in that landscape.” This illustrates the breadth of her inspiration, drawing from music, chance, and even the natural world to discover new sonic possibilities for her guitar.

She uses the analogy of a typewriter with rearranged letters to explain her approach to constantly changing tunings. “If you’re only working off what you know, then you can’t grow,” she stated. “It’s only through error that discovery is made, and in order to discover you have to set up some sort of situation with a random element—a strange attractor, using contemporary physics terms.” For Mitchell, mistakes are not setbacks but essential pathways to innovation. The deliberate introduction of randomness, through altered tunings, keeps her music fresh and prevents her from falling into formulaic patterns. “The more I can surprise myself, the more I’ll stay in this business, and the twiddling of the notes is one way to keep the pilgrimage going. You’re constantly pulling the rug out from under yourself, so you don’t get a chance to settle into any kind of formula.” This restless spirit of exploration is the driving force behind her guitar and her entire musical oeuvre.

Evolution and Adaptation: Lowered Tunings Over Time

Over her career, Joni Mitchell has utilized an astounding number of tunings, reportedly 51 to date. This high number is partly due to the gradual lowering of her tunings over time, with some tunings recurring at different pitch levels. Initially, her tunings centered around open E, subsequently dropping to D and then C, and in recent times, extending even lower to B or A in the bass register. This evolution mirrors the lowering of her vocal range since the 1960s, likely influenced by heavy smoking. This adaptation demonstrates her guitar not only as a tool for creative exploration but also as an instrument that evolves in tandem with her physical and artistic changes.

When performing older songs today, Mitchell typically uses a lowered version of the original tuning. “Big Yellow Taxi,” originally in open E, is now played in a lower open C tuning (C G C E G C). “Cherokee Louise,” recorded in D A E F# A D, is now performed in C G D E G C, a whole step lower. This C tuning, also used for “Night Ride Home,” is reportedly her current favorite. Interestingly, some relative tunings reappear at different registers for different songs, creating connections across her vast catalog. For example, “Cool Water” and “Slouching towards Bethlehem” share the tuning D A E G A D, while tunings for “My Secret Place” and “Hejira” are transpositions of this tuning at successively lower pitches.

These connections allow for a degree of consistency in fingerings across different tunings, but each tuning still presents its own unique sonic universe. “You never really can begin to learn the neck like a standard player, linearly and orderly,” she explained. “You have to think in a different way, in moving blocks. Within the context of moving blocks, there are certain things that you’ll try from tuning to tuning that will apply.” This “moving blocks” approach to the fretboard is a direct consequence of her tuning innovations, requiring a fundamentally different way of visualizing and navigating her guitar.

Her Guitar as an Orchestra: A Multi-Voiced Instrument

The richness and depth of Joni Mitchell’s guitar arrangements stem from her conception of the instrument as a multi-voiced ensemble. Open tunings grant her the freedom to traverse the fretboard in unconventional ways, leading to her signature style of juxtaposing high-fretted notes against ringing open strings. This technique expands the range of her accompaniment, evident in songs like “Chelsea Morning,” where high riffs dance above open bass strings, followed by bass lines moving below open treble strings.

In her later, more radically tuned songs, the open strings take on a drone-like quality, acting as a harmonic thread connecting chords. “It’s like a wash,” she explained, drawing a parallel to her painting process. “In painting, if I start a canvas now, to get rid of the vertigo of the blank page, I cover the whole thing in olive green, then start working the color into it. So every color is permeated with that green… The drones kind of burnish the chord in the same way. That color remains as a wash. These other colors then drop in, but always against that wash.” This “wash” of drone strings adds a unique textural and harmonic depth to her guitar sound, creating a rich and immersive sonic experience.

Ultimately, Joni Mitchell views her guitar as a self-contained orchestra. “When I’m playing the guitar,” she said, “I hear it as an orchestra: the top three strings being my horn section, the bottom three being cello, viola, and bass—the bass being indicated but not rooted.” This orchestral conception underscores her innovative approach, transforming the acoustic guitar into a versatile and expressive instrument capable of conveying a vast range of musical ideas and emotions. Her enduring legacy lies in her ability to continually redefine the boundaries of her guitar, inspiring generations of musicians to explore their own unique sonic landscapes.

[