It’s Black History Month, and it’s time to amplify a vital, yet often overlooked, chapter in music history. Inspired by a dismissive comment from a music critic long ago, this exploration delves into the pervasive myth that “black people just aren’t that into guitar.” This notion, encountered even in academic settings, felt fundamentally wrong then, and with years of accumulated knowledge, it’s time to dismantle it definitively. Let’s challenge the narrow perspectives and historical omissions that have obscured the profound contributions of the black guitar player across genres.

The critic’s challenge was stark: “Name one black guitarist other than Hendrix.” Then, almost as an afterthought, “Or Lenny Kravitz.” The implication was clear: black guitarists were anomalies, not integral figures in the instrument’s rich tapestry. This was 2001, years after Lenny Kravitz had already become a mainstream sensation. His breakthrough hit, “Are You Gonna Go My Way?” released in 1993, was undeniably a tribute to Jimi Hendrix’s iconic style. Kravitz, with his flamboyant stage presence and retro aesthetic, was often marketed as a modern reincarnation of Hendrix. His fame wasn’t solely based on his individual talent; it was fueled by a collective yearning for the return of a guitar icon who looked like Hendrix.

This cultural moment reveals a significant bias in how we perceive guitarists. Around the same time, Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine was revolutionizing guitar playing with his innovative techniques. Guitar publications celebrated him, yet in discussions about contemporary black virtuosos, Morello’s name rarely surfaced, likely because his style diverged from the Hendrix archetype.

The question, “where are the great black guitarists?” was a recurring theme in the 90s and early 2000s, often surfacing amidst the cultural divide between rock and rap. Dave Chappelle even satirized this very question in a sketch, highlighting its presence in the cultural consciousness. While the question itself might not inherently be racist, it often took on racist undertones when perpetuated by white voices, reflecting a deeper historical bias. Eighteen years later, the issue isn’t just about the contemporary scene in 2001; it’s about the historical narrative of the guitar itself.

It’s not about accusing individuals of overt racism. The problem is more insidious: racism by omission. It mirrors the outdated and equally flawed question, “why are there no great female artists?” The answer is not a lack of talent, but a lack of recognition and historical erasure. Great female artists existed, but history books often excluded them, and their contributions were frequently attributed to men. Similarly, systemic barriers and biases have historically obscured the contributions of black guitar players.

collage of famous black guitarists

collage of famous black guitarists

When we discuss “guitarists,” especially in this context, the unspoken assumption often leans towards rock guitarists. But why is this the default? Why are genres like jazz and blues, both deeply rooted in black musical traditions, frequently excluded from the conversation? Is it simply a matter of narrow expectations, where “real” guitar playing is equated with 70s arena rock showmanship? Or is it because these genres are inherently linked to the African diaspora and thus considered “Other,” less assimilated into mainstream white American culture? This exclusion is the first critical flaw in the dismissive claim that “black people don’t like guitar.”

Even within the expansive realm of rock guitar, the contributions of black artists are substantial and undeniable. The pervasive “Hendrix idea” itself becomes a limiting factor. While Hendrix’s skill was undeniable, his playing was celebrated not just for technicality but for its raw passion, showmanship, and almost symbiotic connection with his instrument. He became a martyr of rock, solidifying the guitar solo as a central element of the genre.

However, this focus on the “Hendrix type” leads to the overlooking of guitarists who don’t fit this mold, particularly those who aren’t perceived as virtuosos in the same vein. This bias towards virtuosity marginalizes many instruments. When asked to name three great musicians, most people instinctively think of lead instrumentalists, rarely considering drummers, tuba players, or violists. This isn’t malicious; it’s a form of cultural ignorance that devalues different forms of musical skill.

Consider electronic music. Despite its decades-long evolution and complexity, it’s still often dismissed as not “real” music, and its creators not “real” musicians. This same dismissiveness extends to hip-hop, a genre created and dominated by people of color. Rap is often stereotyped as being solely about producers, DJs, samples, and spoken word, devoid of “real” musical skill, particularly by white audiences. This dismissal conveniently overlooks the immense musicality and technical skill inherent in hip-hop.

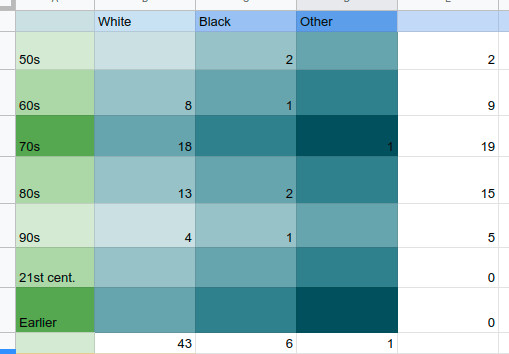

Let’s shift from anecdotal observations to more structured analysis. Consider lists of “greatest guitarists.” One such list, compiled by Loudersound based on 70,000 reader votes, reflects mainstream listener opinions. Analyzing the top 50, the list overwhelmingly features white men known for virtuosity in the flashy, 70s rock style. While it included six black musicians – Chuck Berry, B.B. King, Hendrix, Prince, Slash, and Tom Morello – most are recognized for their soloing prowess, reinforcing the virtuoso bias.

In stark contrast, Rolling Stone‘s updated “top 100 guitarists” list, curated by a panel of experts, presents a significantly different picture. It includes 20 black guitarists and showcases a much broader range of styles. This professional perspective acknowledges artistry and skill beyond the narrow confines of 70s rock virtuosity. This inclusive list is encouraging, suggesting a growing recognition of diverse guitar talents. However, other crowd-sourced rankings still reveal biases, often featuring fewer black guitarists in top positions.

The iconic 70s guitar gods, predominantly white, owe a significant debt to black musical innovation. Blues guitar artistry was always central to the genre, but the emergence of Clapton and Beck-style solos in rock was a pivotal moment. These iconic 60s soloists were essentially the product of B.B. King and T-Bone Walker meeting the psychedelic era. King and Walker pioneered blues soloing, yet their reach was limited by racial segregation, confined to black radio and venues. It was only with desegregation and the rise of white blues-based artists like Eric Clapton that King gained wider mainstream recognition.

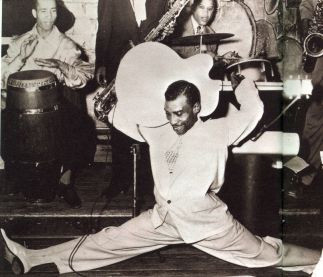

T-bone walker doing a split and playing guitar behind his head

T-bone walker doing a split and playing guitar behind his head

The public’s initial exposure to “great” guitar playing was often through a white, mainstreamed version of rhythm and blues. Beyond B.B. King, the sophisticated, improvised solos of classic rock also draw heavily from jazz, particularly the free jazz movement of the 50s. Thus, the celebrated white guitar tradition is deeply indebted to black musical innovation. Hendrix, the prominent black figure in the “Golden Age of Shredding,” notably had to move to the UK to launch his career, highlighting the racial barriers within the US music industry.

To reiterate, acknowledging Hendrix as an “exception” isn’t to suggest he was the sole black guitar virtuoso of the 60s and 70s. Many talented black guitarists existed, but public perception, shaped by systemic biases, often failed to recognize them. When asked to name a great guitarist, the public’s limited and biased memory often defaults to a narrow, white-dominated narrative.

In conclusion, the notion that “black people aren’t into guitar” is demonstrably false and rooted in historical and cultural biases. The dominance of 70s guitar gods in the public’s guitar consciousness has obscured the broader history and diverse contributions of black guitar players. Furthermore, the frequent exclusion of blues and jazz guitarists from these discussions reveals a narrow definition of “guitar music” itself.

The guitar is undeniably iconic in blues music, challenging the idea that it’s solely a symbol of rock. Has the blues, in its evolution, become a genre that transcends ethnicity, or has it been appropriated, its black origins diluted? Jazz, similarly, while evolving into a multicultural genre, carries its own complex relationship with mainstream recognition. The history of American music is a complex interplay of influence and exchange, a cycle of give and take that should be celebrated.

However, commercialization introduces complexities. White artists have historically benefited from easier access to record deals, radio play, television exposure, and media coverage. “White” is often treated as the neutral default, while “black” is relegated to a niche category. The gatekeepers of media, the critics and TV hosts, were predominantly white, perpetuating this cycle. This creates a circular perception where the “universal” becomes implicitly “white,” making true universality exclusive.

Even in contemporary society, racial biases persist. Studies show that black individuals are still often perceived as less intelligent or capable. These lowered expectations, particularly towards black men, intersect with the male-dominated world of lead guitar. This ongoing bias undoubtedly impacts how black musical achievement, including guitar playing, is perceived and recognized in white America, contributing to the dismissal of genres like hip-hop as less musically valid.

The question “where are all the great black guitarists?” is not a reflection of reality, but a symptom of historical amnesia and systemic bias. This exploration has aimed to illuminate why black guitarists have been historically unseen or unremembered in mainstream narratives. The next step is to celebrate and recognize these overlooked figures. Let’s move beyond the myth and reclaim the stage for the black guitar player.

(To be continued: Part 2 will highlight some of these influential and often unacknowledged black guitarists.)

top 50 guitarists 1

top 50 guitarists 1  Oops I missed one

Oops I missed one