In a previous lesson, we explored the major scale from a melodic perspective. Today, we’re diving into the fascinating world of Guitar Chord Scales. We’ll uncover the chords that naturally arise from the major scale and how understanding this relationship can empower you to write songs with ease and achieve satisfying musical results.

Understanding Chord Structure in Major Scales

Every major scale is inherently linked to a set of seven fundamental chords: three major, three minor, and one diminished. The precise mechanics behind this will be explored in a future lesson. For now, let’s focus on the practical and immediately useful aspects of this concept. Here are key points to grasp:

- Scale-Chord Connection: The chords within a scale are directly derived from the notes of that scale. For instance, the C major scale comprises the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. The corresponding chords for the C major scale are C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor, and B diminished. Essentially, each note in the scale has a related chord.

- Consistent Chord Order: The pattern of major and minor chords within a major scale remains consistent across all keys. This means the sequence in which major and minor chords appear is always the same. The first degree of a major scale always corresponds to a major chord, the second to a minor chord, and so on.

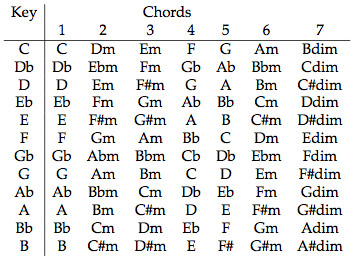

To save you the effort of working through every major scale to determine its associated chords, we’ve compiled a handy table. This table displays all the chords for every major key, making it a valuable resource for your guitar journey.

Chord table for all major keys

Chord table for all major keys

Practical Applications of Guitar Chord Scales

Now that you understand the structure, let’s explore how to put this knowledge into practice. Here are some crucial insights about using chords from guitar chord scales:

- Harmonious Combinations: With the exception of the diminished chord (which we’ll address in more detail later due to its specialized uses), the chords within a given major key can be played in virtually any sequence and still sound musically coherent and pleasing to the ear.

- Selective Chord Usage: You aren’t obligated to use every single chord from a key. For example, in the key of C major, you might choose to work with only C, F, and G chords. Many popular songs are built using a limited selection of chords from their respective key.

- The “Home” Chord: Typically, chord progressions in a major key will begin and conclude on the first chord of that key (the root chord). A progression in C major, for instance, often starts and ends with a C major chord. The first chord in any major key invariably possesses a sense of resolution and finality.

- Key Equivalence: A fundamental concept in music theory is that all major keys are essentially equivalent in structure. The specific key you choose for writing music is less important than the position of the chords within that key. Consider this: the chord progression C-F-G in C major and the progression D-G-A in D major are functionally identical. Both progressions are built using the 1st, 4th, and 5th chords of their respective keys. They will sound very similar, with the primary difference being that the D major progression will be pitched higher than the C major one.

To illustrate this key equivalence, let’s examine the well-known song “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” (originally by Bob Dylan, famously covered by Guns N’ Roses). The song’s chord progression is: G D Am G D C. We can easily determine that this song is in the key of G major: it begins and ends on a G chord, and all the chords used (G, D, Am, C) are found within the G major chord scale (refer to the table).

If we analyze the numerical position of each chord within the key of G major, we get the sequence: 1 (G) – 5 (D) – 2 (Am) – 1 (G) – 5 (D) – 4 (C). This numerical pattern is the essence of the song’s harmonic structure. You can play this same song in any other key simply by applying this numerical sequence to the chord scale of your chosen key. For example, transposing “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” to C major would yield the progression: C G Dm C G F. This process of changing keys while maintaining the harmonic structure is called transposition. It’s commonly used to adjust a song’s pitch to better suit a singer’s vocal range.

Experimenting with Random Chord Progressions

Guitar chord scales also offer a fun and accessible way to begin composing your own chord progressions. Here’s a simple method for generating chord sequences almost effortlessly, using the key of C major as our example:

- Dice Roll for Inspiration: Roll a standard six-sided die three times and note down the resulting numbers. For this example, let’s say you roll a 5, then a 6, then a 4.

- Start at the Root: Begin your chord progression with the first chord of your chosen key. In C major, the first chord is C major.

- Translate Dice to Chords: Look at your first dice roll number (5). Find the 5th chord in the C major chord scale. Referring to the table, the 5th chord is G major. This becomes your second chord.

- Repeat for Sequence: Continue this process for your remaining dice roll numbers. For our example (6 and 4), the 6th chord in C major is A minor, and the 4th is F major.

Following these steps with our example dice rolls (5, 6, 4), we arrive at the chord progression: C – G – Am – F.

Now, play this chord progression on your guitar. Experiment with strumming patterns and try humming a melody over it. You might be surprised at the musical ideas that emerge! If you like what you create, you’ve just composed a song foundation. If not, try again with a new dice roll, or subtly adjust chords within the progression you’ve already generated. With a little experimentation and a touch of musical intuition, you’ll be crafting interesting and original music in no time.

If you’re eager to move beyond simple experimentation and truly master the art of chords and harmony on the guitar, consider exploring more in-depth resources and lessons that delve deeper into music theory and chord vocabulary.