If you’re looking to truly understand your guitar and gain unparalleled freedom across the fretboard, learning the chromatic scale is an essential step. While it might not be a scale you frequently use in your everyday playing, its value is immense, primarily from a theoretical, yet deeply practical perspective.

Navigating the guitar fretboard can be a significant hurdle for many guitarists. It’s a challenge that often leads to frustration and a feeling of being confined to familiar areas of the neck. Many players find themselves stuck in ruts, relying on the same patterns and licks, simply because the fretboard seems too daunting to explore.

If this resonates with you, the Chromatic Scale In Guitar is your key to unlocking the instrument’s full potential. Understanding and practicing the chromatic scale will empower you to:

- Confidently play in all 12 musical keys, eliminating the fear of hitting wrong notes or playing out of key.

- Move seamlessly around the guitar neck during improvisation and solos, opening up new creative avenues.

- Explore diverse chord voicings by playing chords in different positions on the fretboard, adding depth and texture to your playing.

- Break free from repetitive licks and phrases and solo anywhere on the neck, creating your own unique patterns and musical ideas.

Learning the chromatic scale is a crucial step for guitarists seeking to elevate their playing. It’s a pathway to a deeper understanding of music theory as it applies specifically to the guitar. So, let’s dive into everything you need to know about the chromatic scale and why it’s so important for guitarists.

Understanding the Musical Alphabet: The Foundation of the Chromatic Scale

Before we delve into the specifics of the chromatic scale in guitar, it’s crucial to grasp the concept of the musical alphabet. Western music utilizes a set of letters to represent notes, but unlike the regular alphabet, the musical alphabet is concise, containing only 7 letters:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|

‘G’ marks the end of the musical alphabet. After ‘G’, it cycles back to ‘A’. Therefore, notes like ‘H’, ‘I’, or ‘J’ are not part of the musical alphabet and won’t be found on your guitar fretboard in standard notation. You will, however, encounter A, B, C, and so on.

However, Western music comprises 12 distinct notes, not just 7. The letters A through G only account for seven of these. Where do the remaining five come from?

Sharps and Flats: Filling the Gaps

The additional five notes are derived from sharps and flats. A sharp (♯) symbol raises a note by a semitone, while a flat (♭) symbol lowers it by a semitone. These sharps and flats exist between many of the natural notes (A-G). While the letter names are sequential in the alphabet, musically, they are not always a whole step apart.

Most notes in the musical alphabet are separated by a tone, also known as a whole step, which is composed of two semitones, or half-steps. For example, there’s a whole step between A and B, and between C and D.

This means there’s a note in between most natural notes. This in-between note is a semitone higher than the lower note and a semitone lower than the higher note. Between A and B, for instance, lies the note A sharp (A♯) or B flat (B♭).

A♯ and B♭ are actually the same pitch, just named differently. These dual names exist for notes between most of the musical alphabet notes. Between C and D, you’ll find C♯ or D♭.

This concept can seem a bit abstract at first. Think of it mathematically: if A is 1 and B is 2, then A♯/B♭ is 1.5. You can reach 1.5 by adding 0.5 to 1 (A + 0.5 = A♯), or by subtracting 0.5 from 2 (B – 0.5 = B♭). The pitch is identical, just the notation differs.

In practical music, particularly within a key, the choice between sharp or flat notation is governed by convention to maintain clarity within musical scores. However, for understanding the chromatic scale in guitar, it’s most important to recognize that A♯ and B♭, and similar pairs, represent the same sound.

Defining the Chromatic Scale: All 12 Notes

By including all the sharps and flats between the natural notes of the musical alphabet, we arrive at 12 unique notes. These 12 notes constitute the chromatic scale, encompassing all the pitches used in Western music. Here are the 12 notes of the chromatic scale:

| A | A#/Bb | B | C | C#/Db | D | D#/Eb | E | F | F#/Gb | G | G#/Ab |

|---|

Key points to remember:

- Not every natural note has both a sharp and flat note following it. Specifically, there’s no B♯ or E♯, and consequently, no C♭ or F♭. B♯ is enharmonically equivalent to C, and F♭ to E. The 12 notes listed above are the complete set in Western music.

- Each interval between consecutive notes in the chromatic scale is a semitone. The distance from A to A♯ is a semitone, as is the distance from A♯ to B. Therefore, a whole tone exists between A and B. However, between B and C, and E and F, there’s only a semitone because there is no B♯ or E♯.

Remembering which notes lack sharps and flats can be tricky initially. A helpful mnemonic is to recall the phrase “Beautiful Evening**,” associating ‘B’ and ‘E’ with the notes that don’t have sharps immediately after them in the natural musical alphabet sequence.

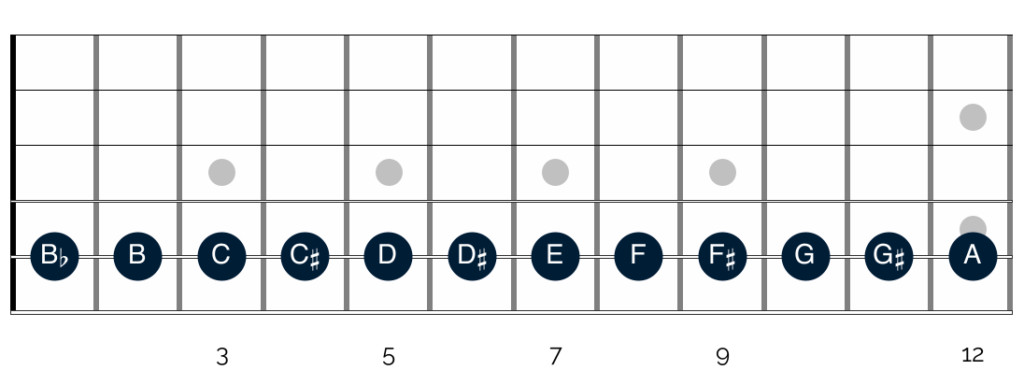

The Chromatic Scale on Your Guitar Fretboard: A Visual Map

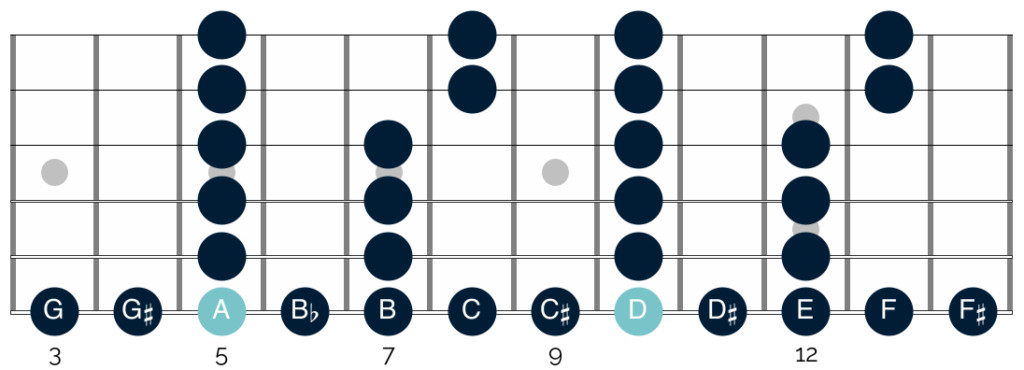

Understanding the chromatic scale becomes much clearer when applied to the guitar fretboard. Let’s visualize the chromatic scale in guitar starting on the note A on the open A string:

The chromatic scale, shown on the A string of your guitar

The chromatic scale, shown on the A string of your guitar

Observing the chromatic scale diagram on the A string reveals two fundamental aspects of the guitar fretboard:

- Each fret represents a semitone. Moving one fret up or down changes the pitch by a semitone. Two frets equal a whole tone.

- By the 12th fret, you’ve played all 12 notes of the chromatic scale. This means you’ve covered every distinct note in Western music.

Crucially, these principles apply to every string on the guitar. The logic is consistent across the fretboard. On any string, moving one fret changes the pitch by a semitone, and by the 12th fret, you’ve completed a chromatic scale from the open string note.

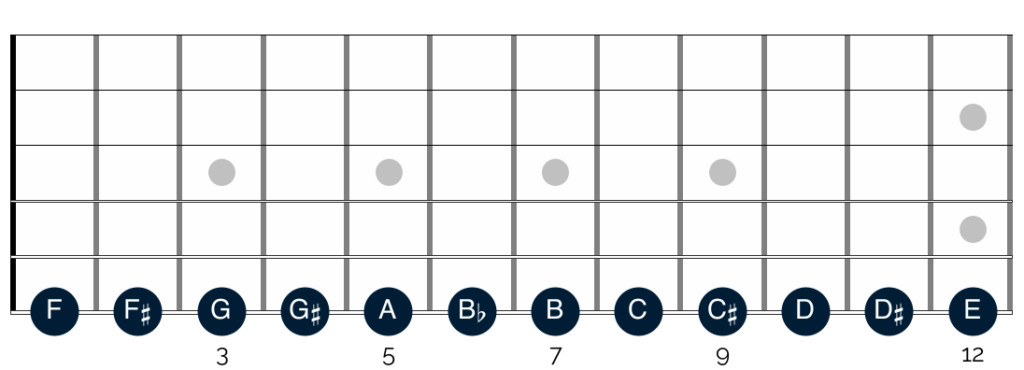

The starting note of the chromatic scale differs for each string, based on the open string’s tuning. Let’s look at the low E string:

The chromatic scale, shown on the low E string of your guitar

The chromatic scale, shown on the low E string of your guitar

Starting with E on the open low E string, each subsequent fret ascends by a semitone through the chromatic scale. By the 12th fret, you’ve again played all 12 notes.

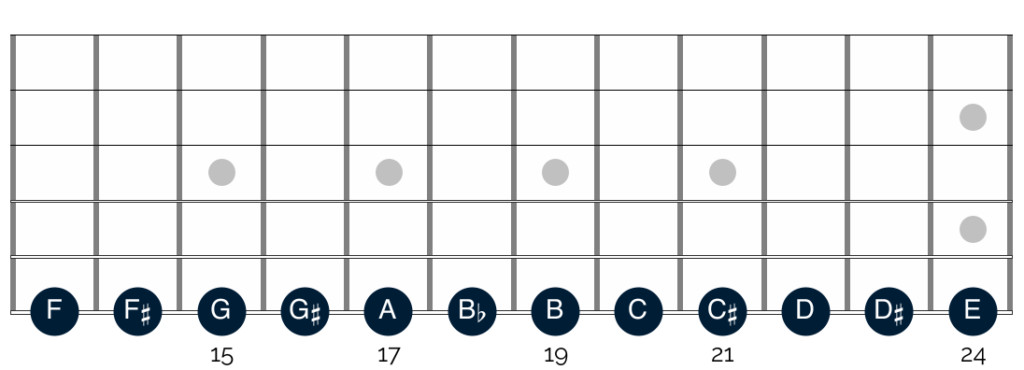

Beyond the 12th Fret: Octaves and Repetition

What happens beyond the 12th fret? The note pattern repeats. At the 12th fret, you arrive at the same note name you started with, but an octave higher.

For example, on the low E string, the 12th fret is also an E, but an octave above the open string E. In terms of the chromatic scale, it’s still considered the same root note, just in a higher register. The sequence of notes after the 12th fret mirrors the sequence before it.

Here’s a visual representation extending beyond the 12th fret on the low E string:

The chromatic scale, shown on the E string of your guitar, above the 12th fret

The chromatic scale, shown on the E string of your guitar, above the 12th fret

As illustrated, the notes repeat after the 12th fret. Guitars with 24 frets allow you to play two full octaves of the chromatic scale on each string. Even with guitars having 21 or 22 frets, the fretboard effectively divides into repeating 12-fret segments. This repetition is why you often see double fret markers at the 12th fret – visually indicating the octave point and the start of the repeating pattern.

Practical Applications: Unleashing the Power of the Chromatic Scale

While the chromatic scale itself isn’t typically used for melodic improvisation in the same way as major or minor scales, its true power lies in providing a framework for understanding the entire guitar fretboard. It’s a pattern of notes that allows you to locate any note, anywhere on your guitar. This foundational knowledge unlocks numerous practical benefits:

Playing in Different Keys: Transposition Made Easy

Knowing the chromatic scale empowers you to play in any key. If you’re comfortable improvising in A minor, for example, you can easily transpose your licks and phrases to B minor, C minor, or any other key.

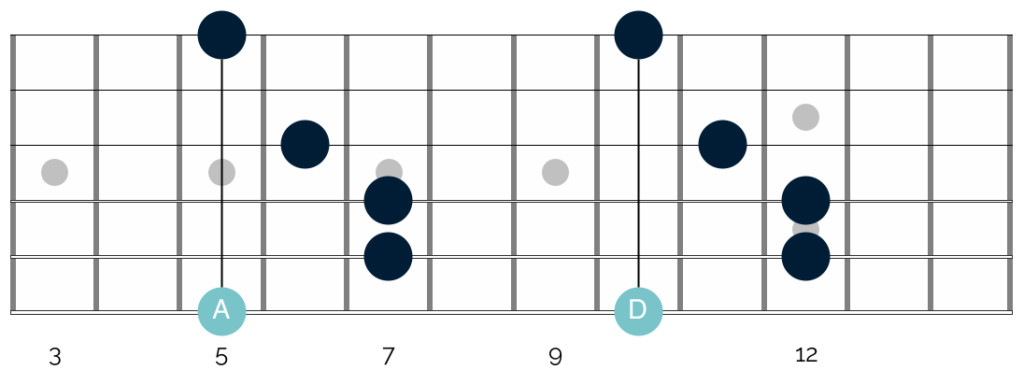

Let’s see how this works visually:

You can use the chromatic scale to move your

You can use the chromatic scale to move your

The diagram shows the chromatic scale on the low E string alongside the A minor pentatonic and D minor pentatonic scale shapes. Notice that the pentatonic shapes are identical; only their position on the fretboard changes.

If you know your A minor pentatonic licks, understanding the chromatic scale allows you to shift those same shapes to start on a B, C, D, etc., on the low E string, instantly playing in B minor, C minor, D minor, and so on.

To play in C minor, for instance, locate the note C on your 6th string. Start your first minor pentatonic shape from that C, and you’re now playing in C minor. From there, you can access all your pentatonic shapes in that new key.

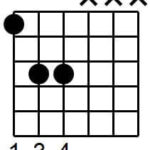

Mastering Movable Chords: Barre Chords and Beyond

The same principle applies to chords, especially barre chords. The chromatic scale provides the roadmap for moving barre chord shapes across the fretboard to create different chords.

You can use the chromatic scale to move barre chords all over your fretboard.

You can use the chromatic scale to move barre chords all over your fretboard.

Barre chord diagrams often don’t explicitly show the chromatic scale, but the underlying principle is the same. The example above shows an A major barre chord shape and a D major barre chord shape. The chord shapes themselves are identical; their position relative to the nut (and therefore, the root note) is different.

If you know an A major barre chord, combining that knowledge with your understanding of the chromatic scale lets you play B major, C major, D♯ major, and any other major chord by simply shifting the same shape up or down the neck, using the chromatic scale as your guide to find the correct root note.

This understanding of the chromatic scale in guitar empowers you to play a vast range of lead lines and chords across the entire fretboard.

Focusing on the Low E and A Strings: A Practical Shortcut

For practical application, you don’t need to memorize the chromatic scale across all six strings initially. Focusing on the low E and A strings provides a highly effective shortcut. There are two key reasons for this:

Firstly, the root notes of most common scales and barre chords are found on the low E and A strings. Mastering the chromatic scale on these strings gives you immediate access to transposing a vast repertoire of scales and chords.

Secondly, as detailed in resources about octave shapes, knowing the notes on the low E and A strings allows you to deduce notes on other strings without memorizing every fret on the entire neck. Octave shapes provide a direct visual and spatial link between the low E and A strings and the rest of the fretboard.

If you’re eager to apply the chromatic scale in guitar to your playing but feel overwhelmed by learning every note everywhere, start with the low E and A strings. This focused approach will quickly unlock practical benefits and build a solid foundation for further fretboard mastery.

Final Thoughts: The Chromatic Scale as a Gateway

The chromatic scale, while seemingly simple, is a fundamental concept that unlocks a deeper understanding of the guitar and music theory. It’s a gateway to more advanced topics like intervals and scale construction, although those are extensive subjects for another time.

For now, grasp the fundamentals of the chromatic scale. Theoretically, it’s crucial for understanding music theory on the guitar. Practically, it illuminates the logic of your fretboard, benefiting both your lead and rhythm playing, and ultimately making you a more versatile and knowledgeable musician.

Start practicing the chromatic scale, focusing on the low E and A strings. Experiment with transposing scales and chords. Let me know how you progress, and if you have any questions, reach out! Leave a comment or email me at [email protected]. I’m always happy to help.