Guitar chord theory can initially seem daunting. Many guitarists, especially beginners, might shy away from diving into the intricacies of chord construction, preferring to stick to familiar shapes and patterns. Like many, for a significant portion of my guitar playing journey, I focused almost exclusively on lead guitar, channeling my energy into emulating guitar heroes like Stevie Ray Vaughan and Gary Moore, while neglecting the foundational aspects of chords and rhythm guitar. Basic chords felt secondary to the thrill of lead playing.

However, realizing the limitations this imposed, I made a conscious decision to explore the world of guitar chords and delve into chord theory. This dedicated effort has profoundly impacted my overall musicianship. My comfort and confidence in navigating guitar chords across the fretboard have grown immensely. Interestingly, this deeper understanding of chord structures has also significantly enhanced my lead guitar playing.

This improvement stems from the fundamental role chords play in music. Solos are almost always performed over a chord progression. Therefore, grasping how chords are built and how they function within music is invaluable, even if your primary interest lies in lead guitar.

Understanding chord structures will empower you to craft more sophisticated and nuanced solos. It allows you to interact musically with the underlying harmony, making your solos sound less like an add-on and more like an integral part of the music. This leads to solos that are not only technically proficient but also more melodic and emotionally resonant.

Furthermore, for aspiring songwriters, a solid grasp of guitar chord theory is indispensable. It provides the tools to create compelling and original chord progressions that effectively convey the intended musical style and emotion.

Guitar chord theory is extensive, far exceeding the scope of a single article. Therefore, this guide will focus on the essential basics. We will lay the groundwork for understanding guitar chord structures, providing you with the fundamental knowledge to become more comfortable with chords and their construction. This foundational understanding will serve as a stepping stone for further exploration and mastery of guitar chord theory.

In this article, we will explore:

It’s important to note that this article is designed to build your theoretical understanding of chord structures and will not be filled with chord diagrams for immediate playing. Practical application and chord diagrams will be covered in future articles.

The aim here is to provide you with the theoretical framework that will make learning and applying different guitar chords significantly easier. Whether you are aiming to improve your rhythm guitar skills, compose your own music, or simply become a more well-rounded musician, this guide to the basics of guitar chord theory will be beneficial. Let’s begin.

The Major Scale: The Foundation of Chord Structures

To truly understand guitar chord theory and how guitar chords are constructed, we must start with the major scale. While it might not immediately seem relevant, the major scale is the bedrock of Western music, including blues, pop, rock, and countless other genres. It’s within the framework of the major scale that the logic of chord construction becomes clear.

If you are unfamiliar with the major scale, it would be helpful to first read an introductory article on the major scale and its patterns before proceeding. However, let’s briefly recap the essentials. The major scale is a seven-note scale. Every musical scale has a specific formula, and the formula for the major scale is:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|

These numbers represent the degrees of the scale. ‘1’ is the root note, ‘2’ is the second note, and so on. In the key of C major, the notes are:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|

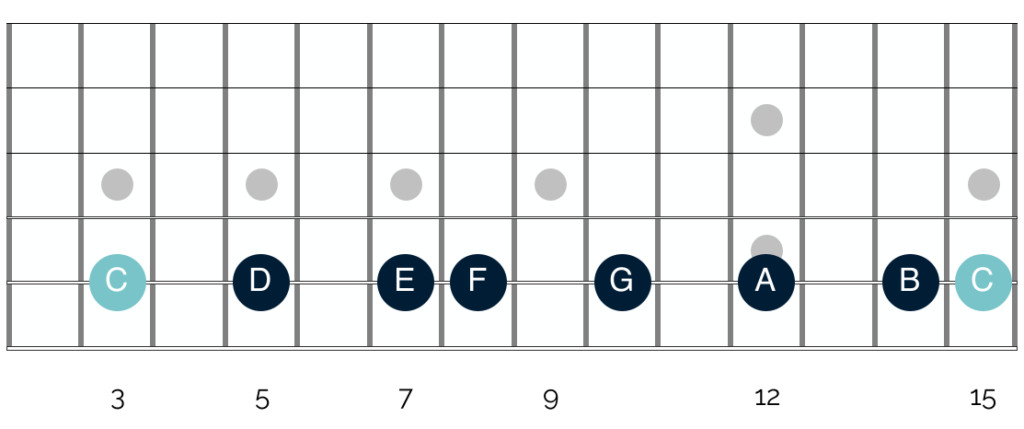

Here’s how the C major scale appears when played across the guitar fretboard:

C Major Scale Fretboard Diagram

C Major Scale Fretboard Diagram

In music theory, a chord is defined as a group of three or more notes played simultaneously. To create a chord, we essentially “stack” at least three notes from a scale together. However, chord construction isn’t arbitrary; it follows a logical system. Understanding this logic, although initially challenging, makes learning, playing, and utilizing chords much more intuitive and efficient in the long run.

Building Triads: The Simplest Chord Structures

The specific notes chosen, the number of notes stacked, and their arrangement determine the type of chord created. While these elements offer vast possibilities, let’s begin with the simplest form of chord structure: the triad. As the name suggests (tri- meaning three), a triad is a chord composed of three notes.

Specifically, a triad is constructed by stacking three notes, each separated by an interval of a third. This refers to musical intervals, and if intervals are a new concept for you, it might be beneficial to first explore an article explaining musical intervals on the guitar before continuing.

Let’s revisit the C major scale:

| Note Name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

The notes highlighted in yellow in the table above (C, E, and G) constitute a C major triad. As mentioned, a triad contains three notes, each a third apart. The concept of a “third” might seem slightly confusing at first. You might notice that C and E are separated by only one note (D), not three, and the same for E and G (separated by F).

The key to understanding “thirds” in this context is to remember to include the starting note when counting. Starting from C: C is the first, D is the second, and E is the third. Similarly, from E: E is the first, F is the second, and G is the third.

Another way to visualize this is by “skipping” notes in the major scale. Start on C, skip D, play E, skip F, play G, and so on. This process of selecting every other note in the major scale is how triads are formed. Simply choose three notes from the major scale, each a third apart, play them together, and you have a triad!

Happy Bluesman Banner Ad

Happy Bluesman Banner Ad

Intervals and Triad Variations

The complexity arises when we build triads starting on different notes of the major scale. In the previous example, starting on C resulted in a C major triad. However, this isn’t the case when starting on other notes of the scale. This variation is due to musical intervals. While all triads are built with notes a “third” apart, the type of third and the overall intervals within the triad change depending on the starting note.

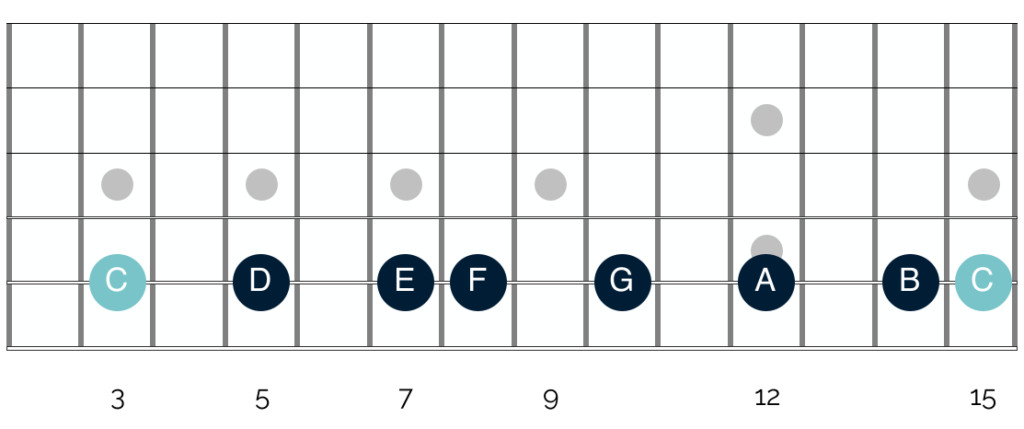

If you are familiar with the major scale, you’ll know that the distances, or intervals, between the notes are not uniform. This is evident when we visualize the scale on the guitar fretboard:

C Major Scale Fretboard Diagram

C Major Scale Fretboard Diagram

Notice how some notes are separated by two frets (a whole step), while others are only one fret apart (a half step). These varying intervals within the major scale become crucial when constructing triads on different root notes.

Even though each triad is built by stacking notes a third apart, the actual intervals between these notes differ, influencing the triad’s sound. Let’s compare a triad built on C with one built on D.

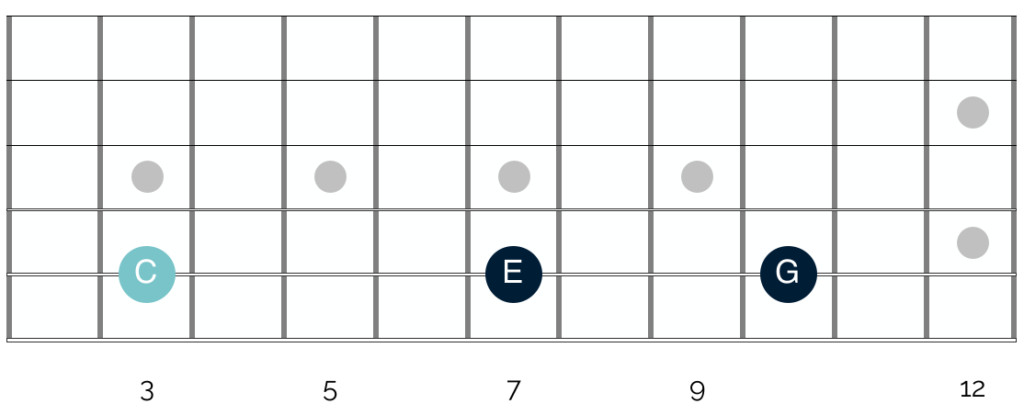

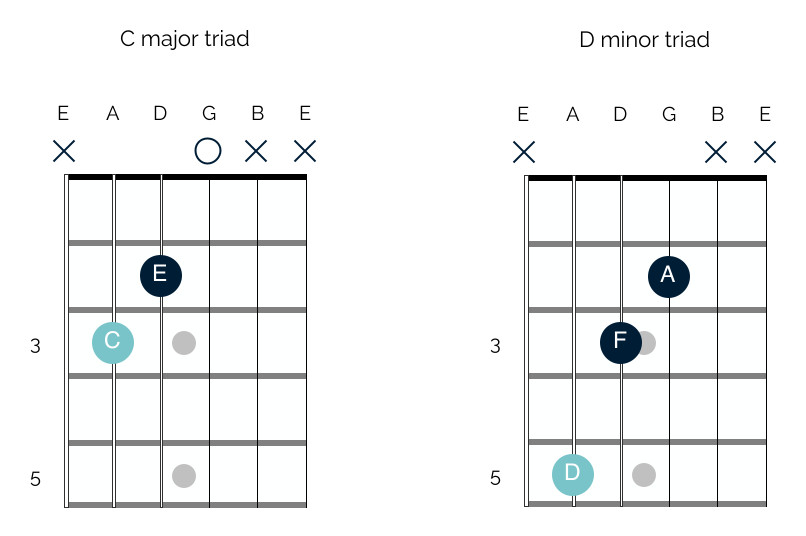

C Major Triad Diagram

C Major Triad Diagram

In this diagram, the root note (starting note) is C, shown in light blue. Observe the fret distances: C to E is 4 frets, E to G is 3 frets, and C to G is 7 frets. Since each fret represents a semitone, this translates to 2 whole tones between C and E, 1.5 tones between E and G, and 3.5 tones between C and G.

Now, compare this to a triad built starting on D:

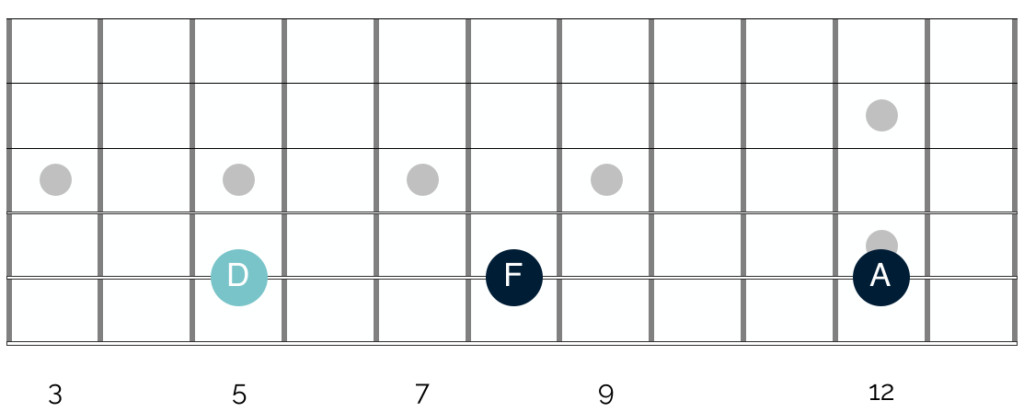

D Minor Triad Diagram

D Minor Triad Diagram

Here, the intervals are different. Between D and F, there are only 3 frets (1.5 tones), while between F and A, there are 4 frets (2 tones). However, like the C triad, the distance from the root (D) to the highest note (A) remains 7 frets (3.5 tones).

If we play the notes of the C triad and the D triad, we hear a distinct difference. The C triad sounds like a C major triad, while the D triad sounds like a D minor triad.

C Major and G Major Chords

C Major and G Major Chords

The C major triad example uses open strings, demonstrating how triad notes can be found within common chord shapes.

Playing both triads will highlight the sonic difference. Major triads generally sound bright and happy, while minor triads have a darker, sadder, or more melancholic quality. This difference in sound arises from the variations in the intervals within each triad, a crucial concept in guitar chord theory.

Major and Minor Triads: Defining the Sound

As we’ve seen, building a triad on C in the key of C major creates a C major triad, while building one on D creates a D minor triad. Let’s examine the interval composition of major and minor triads more closely.

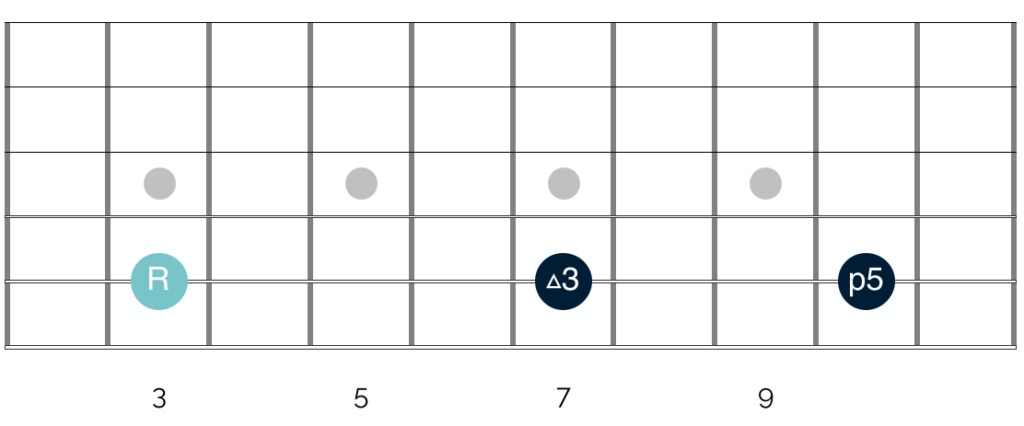

C Major Triad Intervals

C Major Triad Intervals

This diagram focuses on the intervals within the C major triad, not just the note names. The intervals are:

- Root

- Major Third

- Perfect Fifth

The first note is always the root, defining the chord’s name (C for a C chord). A major third is always 4 frets (2 whole tones) above the root. This major third interval is what gives the major triad its characteristic bright quality. The perfect fifth is always 7 frets (3.5 tones) above the root. Perfect intervals are associated with consonance and stability, lending a harmonious and resolved sound to the chord, free of tension or dissonance.

Now, let’s compare these intervals to the D minor triad:

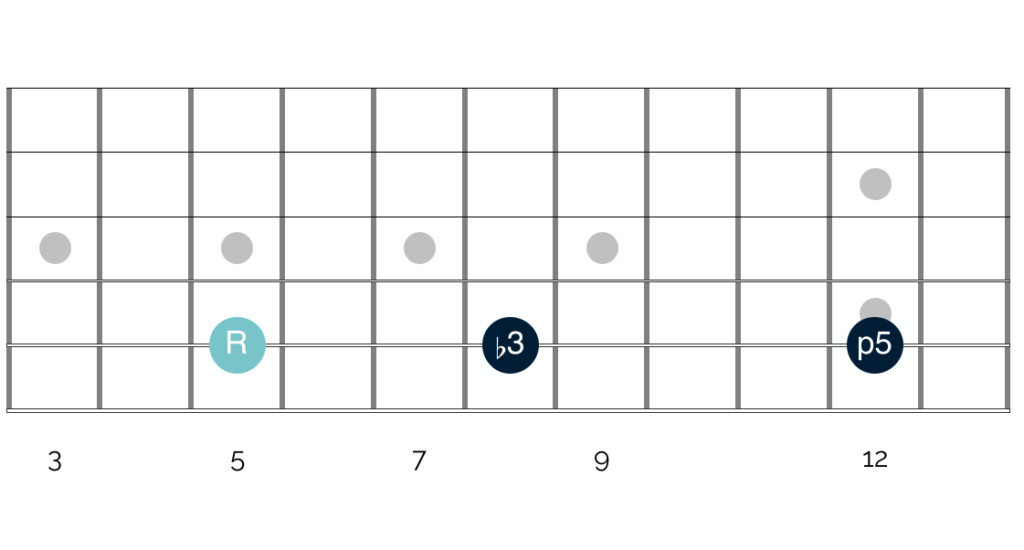

D Minor Triad Intervals

D Minor Triad Intervals

Again, this diagram emphasizes the intervals. The intervals in a minor triad are:

- Root

- Minor Third

- Perfect Fifth

Like the major triad, the minor triad has a root (D in this case) and a perfect fifth. The crucial difference is the third interval. Instead of a major third, it has a minor third. A minor third is always 3 frets (1.5 tones) above the root, one fret lower than a major third. This minor third interval imparts the characteristic sad or melancholic quality to the minor triad.

However, like the major triad, the presence of the perfect fifth in the minor triad still contributes to a sense of stability and resolution, even with its more somber tone. It lacks a dissonant or tense quality.

Harmonizing the Major Scale: Triad Patterns

To further understand guitar chord theory, we can apply this triad-building concept to every note of the major scale. This process, called harmonizing the major scale, reveals the relationship between scale notes and the triads they form.

Let’s revisit the C major scale notes and degrees:

| Note Name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Starting on C, we form a triad by selecting every other note: C, E, G. Then, we repeat this, starting on D: D, F, A, and so on for each note of the scale. When we reach the 7th note (B), we continue selecting notes from the beginning of the scale to complete the triad. For example, starting on F, the triad notes are F, A, and C. For G, they are G, B, and D.

As you perform this exercise, keep these interval rules in mind:

- A major third (4 frets above the root) creates a major triad.

- A minor third (3 frets above the root) creates a minor triad.

- A perfect fifth (7 frets above the root) is present in both major and minor triads.

By harmonizing the major scale, you will discover two key patterns. First, you’ll find a consistent sequence of major and minor triads. Second, the triad built on the 7th degree of the scale will sound distinctly different from both major and minor triads.

Let’s look at the result of harmonizing the C major scale:

| Note Name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triad Notes | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Triad Type | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

As you can see, harmonizing the major scale yields a pattern of three major triads, three minor triads, and one diminished triad. This pattern is consistent across all major scales, regardless of the key. Whether in A major, B major, or D major, the sequence of major, minor, and diminished triads remains the same.

This consistency is significant because musicians use this predictable sequence of triads to build chord progressions. We will explore this further below. But first, let’s examine the diminished triad in more detail, specifically the one built on the 7th degree of the major scale.

Diminished Triads: Adding Tension

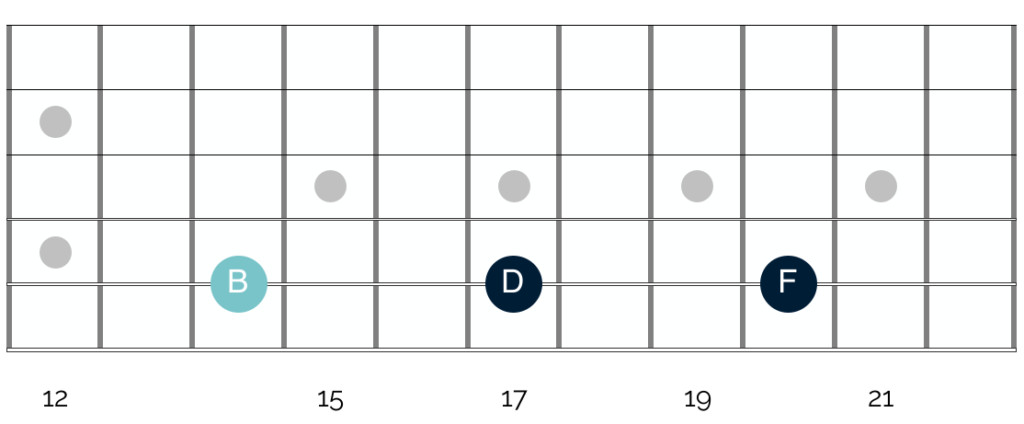

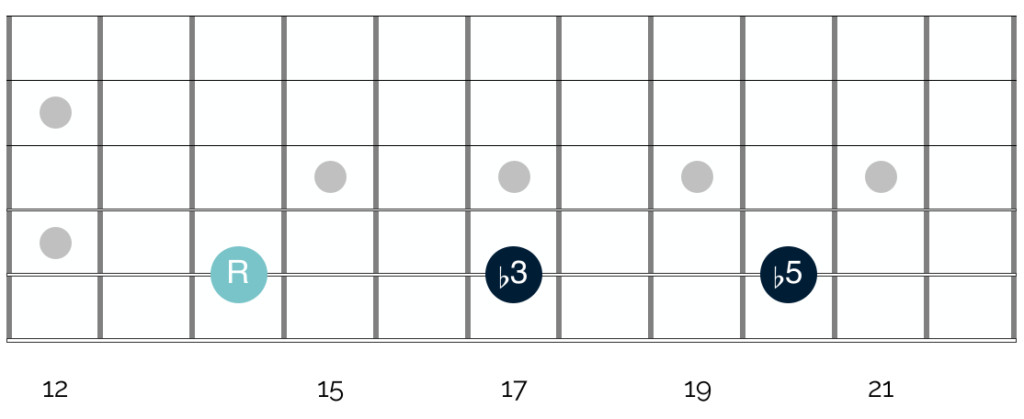

As you may have noticed while harmonizing the major scale, the triad built on the 7th degree of the scale (B in C major) is unique. Let’s examine its structure on the guitar fretboard.

Diminished Triad Diagram

Diminished Triad Diagram

This diagram shows the notes of the B diminished triad (B, D, F). While the triad construction process is the same as for major and minor triads, the resulting chord is neither major nor minor. The key difference lies in the intervals within the diminished triad.

Diminished Triad Intervals Diagram

Diminished Triad Intervals Diagram

The intervals in a diminished triad are:

- Root

- Minor Third

- Flat Fifth

The root and minor third are the same as in a minor triad, with 3 frets between them. The crucial difference is the fifth. The diminished triad does not have a perfect fifth. Instead, it has a flat fifth, which is only 6 frets (3 whole tones) above the root. This diminished fifth interval is what gives the diminished triad its unique character.

A diminished fifth is a dissonant interval, creating a tense and unresolved sound. Consequently, diminished chords, while important, are used less frequently than major and minor triads. They often serve to create tension and harmonic color in chord progressions.

Happy Bluesman Banner Ad 2

Happy Bluesman Banner Ad 2

Triads and Chords: Practical Application

At this point, you might be wondering about the practical application of triads. While understanding triad construction is valuable for theory, we need to bridge the gap to practical guitar playing.

So far, we’ve discussed triads in their theoretical form. However, the term “triad” isn’t as commonly used among all guitarists as “chord.” Beginner and intermediate players are more likely to encounter and use the term “chord.”

To clarify the relationship between triads and chords, let’s define a triad in the context of a chord. As mentioned, a triad is a three-note chord built in thirds. Essentially, all triads are chords, but not all chords are triads.

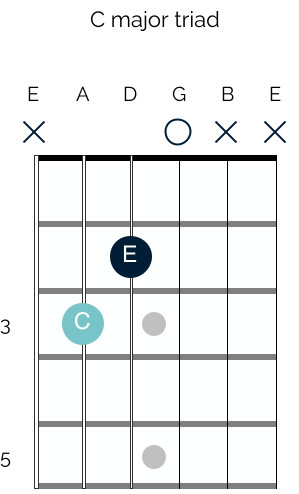

In practice, this doesn’t mean you’re limited to playing only three notes at a time when playing chords on the guitar. Let’s revisit the C major triad diagram:

C Major Triad Shape

C Major Triad Shape

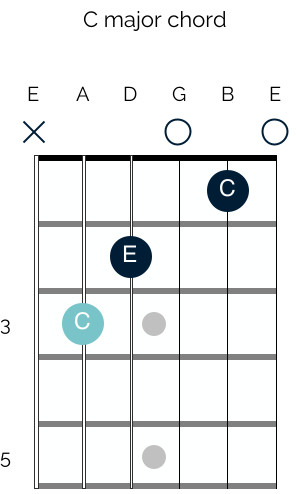

This diagram shows a triad with only three notes. However, if you are familiar with common guitar chords, this shape might not be one you frequently use. You are likely more familiar with this C major chord shape:

C Major Chord Shape

C Major Chord Shape

This diagram shows a standard C major chord. Calling the first diagram a “C major triad” and the second a “C major chord” can be slightly misleading because the terms are often used interchangeably. Both contain the same essential notes: C, E, and G.

The C major triad contains the notes C, E, and G. The common C major chord shape also contains the notes C, E, and G. The only difference is that the chord shape repeats some of these notes. In a typical open C chord, you play C, E, G, C, and E. It’s still considered a C major triad at its core because it’s built upon those three unique notes.

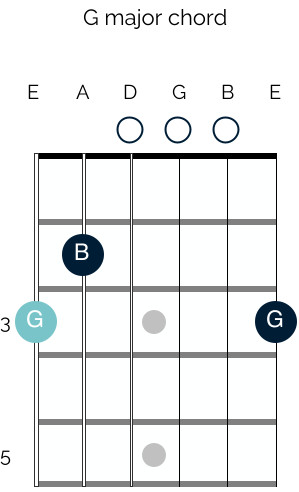

This principle applies to most common major and minor chords. Consider the G major chord. The notes in a G major triad are G, B, and D. Here’s a basic G major triad shape:

G Major Triad Shape

G Major Triad Shape

This simplified G major can be considered a pure triad form, using strings 6, 5, and 4, with the open D string. However, a full G major chord often uses all six strings. As the diagram shows, even in the full G major chord, the notes played are still G, B, and D, with some repetitions across different octaves.

Creating Chord Progressions: Using Triad Harmony

Understanding that common major and minor chords are based on triads connects theoretical knowledge to practical guitar playing. Now, we can explore how to combine these chords to create chord progressions.

Let’s revisit the table showing the harmonized major scale:

| Note Name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triad Notes | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Triad Type | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Chord Name | C Major | D Minor | E Minor | F Major | G Major | A Minor | B Diminished |

| Triad/Chord Number | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii° |

This table now includes Roman numeral notation, a standard way to represent chords in music theory. Uppercase Roman numerals (I, IV, V) denote major chords, lowercase numerals (ii, iii, vi) denote minor chords, and lowercase with a degree symbol (vii°) denotes diminished chords. These Roman numerals represent the function of each chord within the key.

Musicians use these chords, in this specific order, to create chord progressions. Songs in the key of C major often utilize chords from this table. For example, “Let It Be” by The Beatles, in C major, uses the chord progression C major, G major, A minor, F major in its verses – the I, V, vi, and IV chords in Roman numeral notation.

Guitarists and musicians often refer to chord progressions using these Roman numerals. If you hear musicians talking about a “one, four, five” progression, they’re referring to the I-IV-V chord progression. In the key of C, this would be C major (I), F major (IV), and G major (V).

If you were to join a jam session and were told the next song is a “I-IV-V in the key of C,” you would immediately know the chord progression: C major, F major, G major, and back to C major (often).

Beyond Basic Guitar Chord Theory: Extensions and Borrowed Chords

Chord progressions are not always as simple as using only chords strictly within one major scale. There are complexities that add richness and variation to music.

Firstly, musicians frequently venture beyond the chords of a single major scale. While a song might be primarily in one key, songwriters often introduce key changes or “borrow” chords from other keys. Understanding the chords derived from harmonizing the major scale is a crucial first step, but further theoretical knowledge is needed to analyze more complex song structures.

These advanced concepts are beyond the scope of this introductory article but will be explored in future discussions. For now, it’s important to recognize that chord progressions can be more nuanced than simply using chords from a single major scale.

Secondly, guitarists often enhance basic major and minor chords by adding “chord extensions.” These extensions, such as 7th, 9th, or 13th notes, don’t fundamentally alter the major or minor quality of the chord but significantly change its color and feel.

These extended chords are ubiquitous in popular music. You’ve likely encountered them in the form of major 7th, minor 7th, and dominant 7th chords. Understanding basic triad theory makes grasping chord extensions much easier.

For now, focus on mastering the guitar chord theory outlined here. This material is foundational and requires time and practice to fully absorb. Don’t be discouraged if it seems challenging initially. Revisit this information, apply it to your guitar playing whenever possible, and with consistent effort, these concepts will become clearer.

Good luck! Feel free to share your progress or ask any questions in the comments section or via email. I’m always happy to help!

References & Images

Unsplash, Guitar Habits, Wikipedia, Hello Music Theory, Music Notes Now, Wikipedia, Puget Sound, Open Music Theory, Guitar Theory For Dummies, Modern Music Theory For Guitarists