Chet Atkins, a name synonymous with guitar mastery, was more than just a self-taught virtuoso and a pioneer of fingerstyle guitar. He was a visionary record producer who transformed Nashville into a music industry powerhouse and, perhaps most uniquely, the founder of a highly exclusive guitarist fraternity. Membership wasn’t earned through application or audition; it was bestowed by Atkins himself. During his lifetime, only four guitarists received this prestigious nod, the title of “Certified Guitar Player” (CGP). Three of these esteemed musicians, Tommy Emmanuel, John Knowles, and Steve Wariner, continue to carry this legacy today, alongside the late Jerry Reed and Paul Yandell, Atkins’ long-time musical partner, who was posthumously inducted by Atkins’ daughter, Merle.

These Certified Guitar Players are not merely exceptional musicians; they are luminaries in the guitar world. Tommy Emmanuel’s global acclaim has earned him honors ranging from the Order of Australia to Kentucky Colonel. John Knowles, a Grammy winner, transitioned from a career in physics to dedicate his life to music, inspiring countless guitarists through his FingerStyle Quarterly. Steve Wariner’s multifaceted talent shines as a celebrated singer, songwriter, and instrumentalist, boasting numerous No. 1 hits and CMA Awards. Their individual accomplishments could fill volumes, yet they share a common thread: the profound influence of Chet Atkins.

All three CGPs honed their craft through recording and performing alongside Atkins, absorbing his genius and forging their own distinct voices within his foundational style. Despite their shared lineage and mutual respect, Emmanuel, Knowles, and Wariner had never convened as CGPs to collectively reflect on Atkins’ impact – until they gathered at Nashville’s Gruhn Guitars for a unique conversation, filled with music and memories of their mentor and friend.

Photos by Donn Jones

Tommy Emmanuel

Acoustic Guitar: What does Chet Atkins represent to you?

Emmanuel: Growing up, Chet Atkins was the ultimate name in guitar. Later, getting to know him personally, I realized his core was the same as any dedicated musician: an unwavering love for playing. But Chet was so much more. His musicality was vast. He possessed an incredible ear for songs, a masterful approach to production, and a deep understanding of sound. Considering the impeccable tuning on his recordings, especially without digital tuners of the time, his ear must have been truly exceptional.

Wariner: Chet’s genius began with recognizing and nurturing incredible talent in singers and performers. He had an innate ability to spot that spark. My father, who was a fantastic teacher, would play Jim Reeves or Don Gibson records and point out, “Chet produced this.” Everything seemed connected to Chet. My musical world is unimaginable without his influence.

Discovering Chet Atkins’ Guitar Style

Knowles: My journey into Chet’s music started with the Finger-Style Guitar album. I first tackled “The Glow Worm” because it was in A major and seemed relatively simple chord-wise. Initially, I just played the bass line. Then I realized the melody was higher up the neck, while the chords were lower. It pushed me to expand my fretboard knowledge. I could grasp what he was doing conceptually, but physically locating everything was a challenge. Eventually, I learned to navigate it, improvising along the way, which I now understand is a crucial part of the process.

Emmanuel: Early on, I wasn’t aware Chet used a thumb pick. I just heard him playing bass, chords, and melody all at once. Without television to show me how, I figured out how to get that boom-chuck rhythm using a flat pick and then picking out melodies with my fingers. I even learned Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train” this way. That’s how I started fingerstyle, developing the concept and working out tunes. Then, in ’64, his album The Best of Chet Atkins came out, featuring him with a green Gretsch and a thumb pick! It was a revelation. It was like the missing piece – I felt instantly liberated. Switching to a thumb pick unleashed a whole new level of playing for me.

The Effortless Mastery of Chet Atkins

A defining characteristic of Chet’s playing was its apparent effortlessness, almost as if he could play in his sleep.

Emmanuel: Chet was incredibly efficient. He always sought the most economical way to play something, minimizing unnecessary movement. His fingerings were often ingenious and unconventional. He had an innate sense of natural flow in music. If a player seemed to be struggling, Chet recognized a lack of fundamental understanding. The first time my mother saw Chet on TV, she remarked, “He doesn’t look like he’s doing very much!”

Wariner: He was constantly searching for the easiest, most effective way to play.

Emmanuel: If it didn’t feel natural, he wouldn’t do it.

Wariner: Whereas Roy Clark might be doing these elaborate, showy movements up and down the neck.

Emmanuel: Roy Clark was also an entertainer, of course.

Wariner: Exactly.

Knowles: I hadn’t seen Chet on television early on, so I was trying to emulate his sound, but it felt like wrestling an alligator. It seemed too difficult to produce that sound if it was that much work. So, I started focusing on the sounds he created, listening intently to his string movements. If he saw me struggling with a difficult passage, he’d say, “That’s too much work. Look at this,” and show me a more efficient fingering.

Wariner: He once told me, “Son, you’re killing yourself! You’re working yourself to death!”

Emmanuel: One melody lesson I learned from Chet was to imply the harmony first. He would play soft grace notes just before each melody note, creating a subtle harmonic richness. Without those grace notes, playing the melody straight can sound almost like mariachi guitar. But Chet’s approach evoked the smooth harmonies of the Everly Brothers.

Knowles: He had another technique where he’d play a three-note chord using his thumb, index, and middle fingers, but he’d play the index finger slightly ahead of the others. This created a vocal-like effect, similar to two harmony parts, one above and one below the melody. Most players would typically play the thumb slightly early instead.

The Importance of Lyrics and Songwriting

Knowles: I once played “Send in the Clowns” for Chet, the way Judy Collins recorded it. He said, “Well, that’s coming along. Do you know the words?” I admitted I didn’t know all of them. He responded, “I didn’t think so.” That was his way of emphasizing the importance of lyrics in shaping melody, phrasing, and breath in music.

Wariner: He knew every lyric to every song!

Knowles: He’d say, “Remember, the audience knows the words. They’re singing along internally. If you get the words wrong, it throws them off.”

Wariner: John, I remember walking into Chet’s office once. He was recording a tape for Garrison Keillor, bent over his guitar. He said, “Garrison, Steve Wariner just walked in. Steve, grab a bass. Let’s play something for Garrison.” He called out a song I’d never heard before. After we finished, he playfully scolded me, “I can’t believe you messed up the chorus!” I protested, “Chet, I’m sorry I don’t know a song written in 1929!” He just expected you to know every song he knew.

Knowles: That’s how he auditioned people. He’d just jump in and say, “Come on, let’s go.”

Wariner: My first experience with Chet was right before he signed me. He gave me a reel-to-reel tape of outtakes he’d produced for Nat Stuckey and other RCA artists and asked me to learn a few songs. Later, he brought me into Studio B. Looking back, I realize he was testing my voice on tape. After I sang, he casually mentioned, “Paul Yandell told me you play guitar.” I said, “Yes, sir.” Then he said, “I hear you play a lot of my stuff. Play me one of my songs.” I was there to be a singer! That was my Chet Atkins guitar audition, unexpectedly.

Knowles: I was recording some solo pieces in his basement studio. I aimed for the twelfth fret but landed on the eighth by mistake. I stopped playing. Chet’s voice came over the talkback, laughing. He said, “What?” He replied, “Somebody else’s mistakes are always funny.”

The Legacy of Jerry Reed and Paul Yandell

There are two notable absences in today’s CGP gathering – Jerry Reed and Paul Yandell.

Wariner: And Paul Yandell, yes.

Emmanuel: Paul was the last to receive the CGP title.

Wariner: He was incredibly humble and almost reluctant to be in the spotlight.

Emmanuel: It was Paul who suggested to Chet that I should be given the CGP title.

Wariner: Probably the same in my case too. Paul deserves immense credit.

What qualities in Jerry Reed’s music reveal both Chet Atkins’ influence and his own unique evolution?

Emmanuel: You can definitely hear early Chet in Jerry’s playing. He could emulate Chet, and Merle Travis too, better than any of us. But Jerry Reed was also inspired by Ray Charles, which set him apart. He brought a different perspective and developed his own style, often incorporating piano-like licks.

Wariner: Remember, Jerry started as a session musician. Chet encouraged him to make his own records. Often, if you complimented Jerry on his guitar playing, he’d say, “Hey, I’m a songwriter, man.” Or praise his songwriting, and he’d say, “Man, I’m a guitar player.”

Emmanuel: I did something similar to Jerry as I did with Chet – I’d try to get them to play. They’d both initially say, “I’ve stopped playing.” So, I’d play one of their tunes, deliberately getting it wrong. Jerry would inevitably say, “Okay, let me show you how it’s done.” And once he started playing, you could see a lifetime of experience in his hands, even in just a few bars.

Wariner: I didn’t know Jerry well until after Chet passed. The night before Chet’s memorial service, Jerry called me out of the blue. He talked for 45 minutes straight about Chet, pouring his heart out. I wish I had recorded it. We became very close after that.

Forging Individual Paths from a Shared Foundation

Like Jerry, each of you has built a unique guitar style upon the foundation laid by Chet Atkins.

Emmanuel: When I was young, I was deeply influenced by singers and songwriters – Stevie Wonder, James Taylor, Neil Diamond. They informed my songwriting. But I also had this developing guitar technique. For example, I wrote “Son of a Gun,” which has a bridge that Travis or Chet might not have written, yet it’s still rooted in their style.

Knowles: To further illustrate learning from Chet without becoming a clone, two things were key for me. First, studying classical guitar for four years provided me with a different technical foundation, using nylon strings and altering my left-hand approach. Meeting Chet after that period meant I had Chet’s influence but filtered through a classical sensibility. This allowed us to collaborate without me feeling like a Chet imitator. Secondly, when analyzing Chet’s songs, I went beyond just chord names. I looked at how he introduced new ideas or key changes and used those compositional elements to create my own music. It’s about borrowing Chet’s concepts, not just his licks.

Wariner: Early in my singing career, Chet advised me, “You need to find your own path. Don’t copy anybody.” Some of my early records, even produced by Chet, had a Glen Campbell-esque sound, which was great. But Chet insisted, “Be Steve Wariner. Don’t copy me, Glen, or anyone else.” That was crucial. I was trying to emulate others. There’s already one Chet Atkins. Why be a lesser version?

Emmanuel: Especially to young musicians, I emphasize that emulation is a natural starting point in any profession. Someone ignites your passion. Elvis Presley wanted to be like James Dean. Many actors aspired to be Marlon Brando. We learn through imitation. We didn’t aim to become Chet Atkins, but we were drawn to his playing and naturally tried to learn from what we loved.

Sleight of Hands: Chet Atkins’ Guitar Techniques

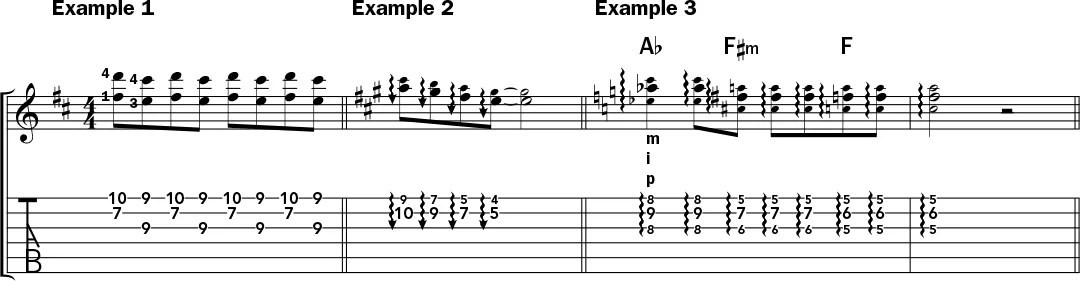

In their time with Chet Atkins, Tommy Emmanuel, John Knowles, and Steve Wariner absorbed invaluable lessons, particularly in the subtleties of fretting and picking techniques. As Knowles demonstrates in Example 1, inspired by Atkins’ “Happy Again,” efficient fretting-finger movement creates smooth, melodic lines. Instead of conventionally sliding dyads in parallel on strings 1 and 3, Knowles maintains seventh position, anchoring his first and third fingers on strings 2 and 3, and using his fourth finger to slide between frets 10 and 9 on string 1.

Chet Atkins guitar lesson example 1 music notation

Chet Atkins guitar lesson example 1 music notation

When playing dyad phrases, guitarists often apply equal emphasis to each note. However, as Emmanuel illustrates in Example 2, he learned from Atkins to execute double-stops with downward rakes, emphasizing the lower voice notes—a nuanced technique reminiscent of the Everly Brothers’ vocal harmonies.

Knowles presents a more complex variation in Example 3. Atkins sometimes surrounded melodies with both upper and lower harmonies, creating three-note block chords. To achieve this, Knowles picks the middle note of each chord first with slight emphasis, then quickly articulates the lower and higher notes with his thumb and ring finger, respectively. This results in a rich, choir-like sound, truly befitting a Certified Guitar Player. —Adam Perlmutter

The Enduring Chet Atkins Appreciation

Since 1985, the Chet Atkins Appreciation Society has held its annual convention in Nashville. The inaugural event drew around 70 attendees, including Atkins himself. In recent years, over 1,000 enthusiasts have gathered at the Music City Sheraton Hotel for the four-day celebration. They come from across the globe and locally, guitar cases in hand, participating in workshops, attending concerts by top fingerstyle players, and jamming together in lobbies and hallways, sharing techniques and passion.

In the convention lobby, Mark Pritcher, the Society’s president, is a central figure. A family practice physician in Knoxville for most of the year, he becomes a convention hero, having co-founded the Society in 1983 with Jim Ferron and leading it since Ferron’s retirement in the early 90s.

“Chet was undeniably a guitar genius,” Pritcher reflects. “But his legacy extends beyond music. He had an extraordinary way of connecting with everyone, treating the president of RCA and a shoeshine person with equal respect. That inclusivity is a key lesson he taught me.”

Fingerstyle virtuoso Pat Kirtley echoes this sentiment. “I remember walking down the hallway late one night and seeing about 15 teenagers, not causing trouble, just playing guitar for each other. They had found a place of complete acceptance. That’s when I realized the true accomplishment of this convention.”

Forrest Smith, a 34-year-old amateur guitarist and a second-time convention attendee, emphasizes the community aspect. “I played casually for 20 years without serious dedication. Coming here reignited my passion. The community, from Tommy Emmanuel to beginners like me, is incredibly inspiring. Learning a song in this style and having others encourage you is amazing. I’ve made great friends here—and it’s given the guitar back to me.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.