[Editor’s Note: This article is inspired by an interview originally published in the August 2013 issue of Classical Guitar magazine.]

Inspired by an interview by Guy Traviss

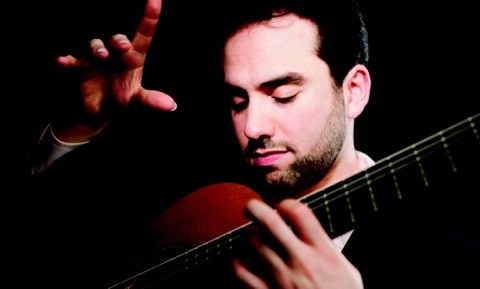

Adam Levin Portrait

Adam Levin Portrait

The realm of classical guitar resonates across borders, connecting diverse cultures and traditions. While regions like Spain are historically celebrated for their guitar heritage, the instrument’s global appeal extends to countries like Hungary, where craftsmanship in instrument making is also valued. In this spirit of global guitar artistry, we explore the journey and perspectives of Adam Levin, a distinguished classical guitarist whose dedication and innovative spirit have carved a unique path in the contemporary music scene. Levin’s story, marked by a strong work ethic instilled from a young age, reveals the dedication required to master the instrument and build a thriving career in the arts.

Your early introduction to the guitar was characterized by a remarkable work ethic. Could you share how you began playing and what motivated you to dedicate yourself so intensely to it?

My introduction to the guitar was entirely thanks to my father. He initially played the violin from a young age, but when Beatlemania swept through, he, like many others, felt the allure of the guitar. It was simply “cooler” than the violin at that time! He embraced the guitar and has been playing ever since, exploring blues, jazz, bluegrass, and even classical music. His musical heroes were a diverse mix, ranging from classical masters like Andres Segovia to blues and rock icons like Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix, and jazz virtuoso Joe Pass. I vividly remember listening to these legends with him, absorbing his insights into what made each of them so extraordinary.

Later, when he suggested that my sister and I take up classical guitar, my father also returned to the instrument. Over the years, he delved into some of the most significant pieces in the solo classical guitar repertoire. I have cherished memories of practicing the works of great Spanish composers—Albéniz, Granados, Turina, and De Falla—alongside my father. Every morning at 5:30, he would sit across from me in the living room with his Wall Street Journal, occasionally offering comments from behind his newspaper. I could also hear my sister practicing Segovia scales and Sor studies in the next room. For a middle schooler, while my friends were still asleep, these mornings felt like a journey back in time, connecting me to a culture and spirit quite different from my own contemporary world.

Honestly, finding the motivation to practice at that hour was often a challenge. But my father was determined to instill the discipline necessary for mastery. I remember the sound of his footsteps coming down the hallway, the knock on my door, and my groans and complaints about waking up so early. However, I rarely won those morning battles. He had two main arguments. First, he pointed out the limited time available after school due to sports, homework, social activities, and general tiredness. His second, rather humorous, rationale was that farmers had to wake up at dawn to milk the cows, so I needed to wake up to practice, and then I’d get my glass of milk. I resented it then, but now I can laugh about it! Despite the sometimes strained relationship with the guitar during my upbringing, I am incredibly grateful for my father’s dedication to our education, his effort to instill a strong work ethic, and for sharing something that has been a lifelong passion for him. This early discipline profoundly influenced my own drive to succeed in music and my perhaps obsessive work ethic today. Even now, when I return home to the Chicago area to perform, my father still sits with me as I practice, though the commentary has changed. Now, it’s less about general observations and more likely to be a quiet, “that’s not right, play it a little slower.”

Adam Levin performing “L’anima Sola” from Eduardo Morales-Caso’s Suite para Guitarra Il Sogno Delle Streghe.

Becoming a NAXOS recording artist places your work within a specific context, alongside a roster of distinguished guitarists. How did this influence your approach to designing your album?

NAXOS’s commitment to cataloging and globally distributing new repertoire perfectly aligned with my own aspirations to bring contemporary guitar music to a wider audience. Over the years, I’ve been inspired by many guitarists who have recorded significant new works, and this motivated me to envision a NAXOS recording that would showcase a substantial body of important, modern guitar repertoire. With a focus on innovation and a departure from conventional paths, I embarked in 2008 on a quest to explore the works of living Spanish composers from the last four generations who have significantly contributed to the evolution of Spanish composition. What began as a Fulbright Scholarship proposal evolved into a project encompassing 30 newly commissioned virtuoso works for solo guitar. The project expanded beyond my initial expectations, requiring a prominent platform to give it the reach it deserved. Consequently, I proposed a four-volume recording project to NAXOS, and I released the first volume, 21st Century Spanish Guitar, in May 2013. Three more volumes are set to follow, further exploring this rich and evolving musical landscape.

Spanish contemporary repertoire has been a central focus of your recent work. What drew you to this particular area, and what series of events led to this significant project?

My deep dive into Spanish contemporary music began when I served on the jury of a major international guitar competition in Colorado. Listening to nearly 50 guitarists perform, I noticed a recurring theme: the Spanish composers they played were almost exclusively Rodrigo, Granados, Turina, and Ascencio. Like myself, these guitarists predominantly adhered to the established masterpieces of the 19th and early 20th centuries. For years, I had been curious about what came next. Had Spain ceased to produce great music? What was happening in the contemporary Spanish guitar music scene? As a student, I learned Spanish music, but often without a deep understanding of its cultural context and origins. My experience with the Spanish language was similar – I learned enough to get good grades in Spanish class, but not much beyond that. This curiosity to truly master a second language, to connect with the homeland of the “Spanish sound,” and to discover the direction of 20th and 21st-century Spanish composition led me to apply for a Fulbright Scholarship.

Something that has always resonated with me is sharing music, especially guitar music, in new and unfamiliar settings, reaching audiences who might not typically encounter classical music. The outreach work I had done in the United States as a music advocate could be expanded on a larger scale as a Fulbright Scholar, allowing me to share American music with European audiences and, upon my return, introduce new Spanish music to American listeners. My Fulbright experience provided the perfect opportunity. My initial plan was to study and perform existing 20th and 21st-century Spanish guitar repertoire. During my first two years in Spain, I enrolled at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música in Madrid and studied with the esteemed Spanish guitar virtuoso Gabriel Estarellas. Maestro Estarellas was instrumental in introducing me to the key works and composers of the preceding 80 years, including members of the Generation of 1930: Anton García Abril, Xavier Montsalvatge, Leonardo Balada, Cristobal Halffter, Tomas Marco, and Luis de Pablo, among others. Remarkably, Estarellas has premiered over 300 new works for guitar in his career. This was a profound inspiration, so much so that it redirected the course of my Fulbright project. It felt like the right moment in my career to contribute to the field, just as my mentors Eliot Fisk, Oscar Ghiglia, and Gabriel Estarellas had done.

I embarked on a new journey to find the most compelling composers of the last four generations and commission them to write new pieces for me. This was an exciting endeavor that involved meeting and befriending many prominent figures in the compositional world. Many of them generously welcomed me into their homes whenever I visited Spain. I spent considerable time attending concerts and immersing myself in music. Let’s just say my iTunes bill increased significantly! My relationships with two composers eventually led to two commercially released recordings: Music from Out of Time, and Fuego de la luna: Levin Plays Morales-Caso. I aimed to commission works that represented the full spectrum and diversity of Spanish composition. During my second year in Spain, I received a fellowship from the Program for Cultural Cooperation, which allowed me to research Spanish composers who had immigrated to the United States. I focused on three composers in particular: Leonardo Balada, Ricardo Llorca, and Octavio Vazquez. Engaging in conversations about their careers, they each composed fantastic new works for solo guitar for me. The project truly snowballed, with one composition leading to the next. In my mind, it became a natural progression from the 30 short works commissioned by Colien Honegger in 1998 from contemporary Spanish composers, published as Album de Colien.

In my third year in Spain, supported by a Kate Neal Kinley Fellowship, I dedicated a significant portion of the year to performing many of these new works across Spain and Europe, and to commissioning even more pieces for the project. When I returned to the United States in the summer of 2011, I sought a home for these works. I reached out to numerous major record labels in the US, and NAXOS enthusiastically embraced my project across four volumes. The first volume is complete, and the second is in progress. Additionally, a seven-volume companion publication featuring all the commissioned works will be published by Brotons and Mercadal Editions in Barcelona. This extensive project represents four generations of Spanish composers, both male and female, and encompasses a wide range of styles, from neo-baroque to fractal compositions. The subsequent recordings promise to be even more adventurous!

How do you perceive the evolution of Spanish musical language? Does it still retain elements of the nationalist aesthetic popularized by Albéniz and others?

Advertisement

I’ve observed that Spanish composition has undergone another significant shift, entering what I consider to be a new renaissance. While 19th and early 20th-century Spanish composers often looked to France for inspiration, today’s Spanish contemporary masters are drawing from a more global range of influences, spanning centuries and cultures. Spanish composition today is incredibly rich, diverse, and cosmopolitan, encompassing a spectrum from neo-baroque and nationalist aesthetics to incredibly complex fractal compositions. While echoes of the Spanish nationalist “sound” still exist, the overall scope has broadened and diversified considerably. Between 1930 and the present, Spain has experienced profound social, cultural, and political transformations, from Franco’s oppressive regime and Spain’s isolation to democracy, increased immigration, and capitalism. This evolution has brought a wealth of new ideas, cultural exchange, innovation, and global integration. I initially went to Spain expecting to find a homogenized, nationalist culture, but I discovered a very different reality – a Spain that is regionally distinct, culturally diverse, and forward-thinking. These commissioned works, spanning four generations of composers, also provide a fascinating way to trace the evolution of composition over the past 80 years.

Projects of this magnitude often lead to new explorations. What areas are you interested in pursuing next?

I have two main projects that I am eager to explore in the near future. The first is a deep dive into American music, and the second is an exploration of my Jewish heritage through music. I recall giving a recital in Spain where I performed Spanish music, and the organizers commented not only on the performance quality but also on how intriguing it would be for the audience to hear music from my own culture and heritage. So, the following year, I returned and presented just that, and it was very well-received. I would like to record an album dedicated to American composers, showcasing the breadth and depth of American classical guitar music.

Currently, I am also developing a program featuring works by Jewish composers and non-Jewish composers who have been inspired by Judaism. This program will include pieces by Jewish composers such as Ernst Bloch, Arnold Schoenberg, George Gershwin, and Robert Beaser, alongside works by non-Jewish composers like Maurice Ravel and Lorenzo Palomo. This project aims to highlight the richness and variety of music created by Jewish composers and to demonstrate how Jewish culture and traditions have inspired composers from diverse backgrounds.

A question often on the minds of readers is how musicians build a career in the arts in the 21st century. What advice would you offer to aspiring guitarists today?

I believe a comprehensive approach is essential for a successful music career today. The ingredients for success can seem elusive, requiring both passion and discipline to create the right combination for career advancement in the performing arts. Many people ask me, “What do you do all day?” Unlike many professions with established structures and routines, musicians must create their own infrastructure and daily regimen. Setting boundaries is crucial to avoid inertia. I know from personal experience that without specific daily goals, it’s easy to become unproductive. I have learned to develop a daily routine that keeps me focused and on track.

This leads to my next point: an entrepreneurial spirit and the ability to think innovatively are vital. To simply replicate what has already been done is limiting. One must seek new possibilities and offer a fresh perspective. In my view, new music represents the next frontier. I see it as similar to investing in the stock market. You research a stock, monitor its performance, and then decide whether to invest. You invest because you believe there will be a return. I believe the same principle applies to new music. By investing in new compositions, you are betting on their potential to become part of the standard repertoire, leading to future performances and recordings. It’s a strategic investment in the future of music.

Being a jack-of-all-trades is also increasingly important. The notion that winning competitions automatically guarantees a career is misleading. Competitions are just one of many tools for building a portfolio. They are valuable for refining technique, building confidence, and networking within the international guitar community. However, competitions can sometimes inadvertently promote a homogenization of playing styles. Beyond solo performance, exploring the richness of chamber music is essential. Chamber music offers a wonderful opportunity to step outside the “guitar bubble” and engage with the broader classical music world. Collaborating with other musicians allows guitarists to perform music by composers who may not have written specifically for the guitar. It opens doors to different musical circles, broadening horizons and creating more performance opportunities.

Refining one’s artistic message is critical for career development. Simply playing well is not enough. Communicating about your music, your intentions, and your artistic vision is paramount to crafting your personal brand and image. While “branding,” “image,” and “marketing” might sound unappealing to some musicians, they are realities of today’s musical landscape. We must all cultivate our unique artistic voice. My long-time mentor, Eliot Fisk, was instrumental in helping me define my niche and become an advocate for the guitar and the music I perform.

Creating a catalog of recordings is another crucial component of building a lasting legacy. From self-produced albums to recordings with established labels, recordings are an ongoing way to communicate with your audience. You never know which piece or recording will become a benchmark for your interpretation.

There is no single formula for building a successful career. I am still navigating this myself, but I have found that a multifaceted approach has been effective so far. Continuously re-evaluating your musical approach, maintaining discipline, having a strong work ethic, and yes, a bit of luck, are all essential elements for a fulfilling career.

Duo Sonidos is central to your musical activities. Why have you placed such emphasis on this particular ensemble?

Duo Sonidos, my chamber music partnership with violinist William Knuth, is indeed a primary focus. We have been performing together for almost seven years, since meeting in graduate school at the New England Conservatory in Boston. Will had just returned from Vienna, Austria, where he spent two years as a Fulbright Scholar, and I had just completed my undergraduate degree at Northwestern University near Chicago. Will was seeking something different from the traditional string quartet experience, and I was looking to expand into the string world. Our exploration of violin and guitar literature began with works by De Falla, Paganini, Piazzolla, and contemporary Israeli composer Jan Freidlin. With encouragement from Eliot Fisk, Nicholas Kitchen, Paul Biss, and Lucy Chapman, we decided to pursue this collaboration professionally. This partnership has successfully elevated the guitar beyond the guitar world, placing it within the broader string and chamber music realms. Simultaneously, it showcases the violin in its diverse capacities. We have made significant strides in establishing ourselves as a long-term, innovative chamber music ensemble. This is evidenced by new commissions, positive critical reception of our debut recording in BBC Music Magazine, American Record Guide, Classical Guitar magazine, and Fanfare, as well as an expanding international performance schedule. We are effectively advancing our mission, securing exciting invitations from major concert series across the country. While some established chamber music series in the United States can be quite conservative in their programming, often focusing on trios, quartets, and solo pianists, we have convinced many prominent presenters that Duo Sonidos offers an exciting and pioneering approach. Our image and programming, which blends new works with fresh arrangements of masterworks, appeals to both seasoned subscribers and new audiences. We leverage both the popular and classical appeal of each instrument to generate interest in our unique combination. When curating a concert program, we prioritize works that genuinely highlight the collaborative nature of the instruments, where both guitar and violin perform on equal footing. At the same time, we include pieces that showcase the virtuosity of each instrument, such as Robert Beaser’s Mountain Songs, which demands significant technical skill on the guitar, or Fritz Kreisler’s dazzling violin showpieces.

Currently, we are touring with a “Baroque-Folk” program. The first half explores works originally for violin and continuo, including Handel’s Sonata No. 4 in D Major, which is truly sublime, Corelli’s famous Sonata No. 12 “La Follia,” ingeniously using a Portuguese dance motif in a theme and variations, and Fritz Kreisler’s Variations on a Theme by Corelli, which Kreisler initially presented as a work by Corelli himself, revealing its true authorship later. Realizing the figured bass parts for guitar has been challenging but also a valuable exercise for me. As our concert schedule has become increasingly demanding, we have enlisted the help of Allen Krantz, a wonderful composer and guitarist, to transcribe works that I no longer have time to transcribe myself. One piece we particularly enjoy performing is Bach’s B minor Partita for solo violin or guitar, but in an unconventional format! Each movement in this suite is followed by a “double” variation, and we superimpose one movement over its double, playing them simultaneously. It works surprisingly well, which is not entirely unexpected since the doubles are embellishments of the preceding movement. We were initially hesitant to present such a well-known work in such an unconventional way, but after performing it, we were convinced of its merit! We believe Bach himself might have appreciated this fresh perspective.

We also perform works that draw inspiration from diverse folk traditions around the world, including Cuba, Spain, and the United States, by composers like Eduardo Morales-Caso, Xavier Montsalvatge, and Robert Beaser. Our next recording project, планируем release early next year, will feature works primarily inspired by folk music from Hungary, Spain, Poland, Cuba, and America. Through innovative transcriptions, our aim is to offer a fresh perspective on excellent chamber music from the last century originally written for voice and piano or violin and piano. We also remain committed to expanding the repertoire for violin and guitar duos through new commissions. This project will include works by Lukas Foss, Karol Szymanowski, Béla Bartók, David del Puerto, and Xavier Montsalvatge.

The program reflects our pride in our individual heritages. William’s background is Polish, and mine is Jewish. We selected chamber works for this album that draw inspiration from these vibrant cultures. These include three transcriptions from Karol Szymanowski’s violin and piano works: The Dawn and Wild Dance (co-composed with Polish violinist Paul Kochanski), and Szymanowski’s adaptation of Kurpian Song, all referencing traditional Polish music and folklore. Lukas Foss’s Three American Pieces is a profound work that captures the essence of America through its virtuosity, expansiveness, and lyrical character. While this piece reflects our shared American background, it also represents American music from a Jewish composer, someone William has personally collaborated with in the past.

We are particularly excited about our recent adaptation of Xavier Montsalvatge’s masterpiece, Cinco Canciones Negras, originally for mezzo-soprano and piano, based on the evocative lyricism of music from Cuba and the West Indies. These songs presented both a challenge and an opportunity as we worked to capture the essence of the vocal and piano parts idiomatically on the guitar and violin. Just as Manuel De Falla’s Siete Canciones Populares Españolas has become a staple for almost every instrumental combination, we foresee a bright future for this transcription in chamber music settings.

You are also involved in numerous community music projects. How did you become involved in these initiatives, and what value do you believe they bring?

Music activism is integral to my broader vision as a music entrepreneur and a core component of my career plan. For centuries, classical music has often been perceived as exclusive, expensive, and inaccessible to the general public. Historically, it has been primarily available to the wealthy elite and those who could afford music education for their children. However, the political, cultural, and social landscape of the 20th and 21st centuries has shifted dramatically. Globalization has expanded worldwide networks, bringing people from diverse backgrounds together. The internet has revolutionized the exchange of information and ideas, connecting people across cultures and traditions. As a musician, I feel a responsibility to help break down the cultural, social, and economic barriers that prevent people from accessing music education. This commitment has allowed me to broaden my humanitarian scope by introducing classical music to individuals who have been marginalized from the cultural mainstream due to crises, unforeseen circumstances, or economic and educational limitations. The guitar is an instrument with which many people in America feel an affinity, although not everyone has had exposure to classical guitar. People who might rarely consider attending a string recital or an orchestral concert are often drawn to the guitar and curious to hear various styles of music played on it. In this sense, it is an ideal “gateway instrument” to introduce audiences to the world of Bach, Albéniz, and Walton.

My classroom performances have allowed students to experience a form of music they may never have encountered before, potentially inspiring them to pursue creative outlets beyond the classroom. The therapeutic benefits of music in treating mental illness and various physical ailments are well-documented and have been a vital part of hospital programs since its formal introduction as a healthcare discipline at the University of Michigan approximately 60 years ago. Music offers a range of palliative and lasting health and cognitive learning benefits. It fosters social connection among individuals in disconnected or alienated groups, and it provides a voice for emotions, a medium for emotional expression, exchange, and mastery.

My mission is straightforward: to take the guitar into uncharted territory – new music, innovative teaching methods, broader community engagement and participation. As a Boston Albert Schweitzer Fellow, I designed and implemented a multifaceted outreach program encompassing healthcare, education, and community welfare. In Madrid, as a Fulbright Scholar, I collaborated with the U.S. Embassy to create educational programs that offered broad exposure to world music for students in bilingual schools. Music outreach has enabled me to become a community leader while sharing an art form that has brought peace, unity, and fulfillment to my family and my life.

Whenever I mentor young people about pursuing a career in music (something I’m still learning myself!), I emphasize the word “dynamic.” Performance outreach provides a unique opportunity to refine your artistic message, gain performance experience, contribute to your community, educate the next generation of young learners, and cultivate future audiences for music. Combined with a broader performance and teaching career, this approach helps to shape a vision for the 21st-century musician.

To learn more about Adam Levin’s activities since this 2013 interview, click here.

Adam Levin in Concert

Adam Levin in Concert