Understanding the anatomy of your acoustic guitar is fundamental for any player, from beginner to seasoned professional. Knowing the function of each part not only enhances your appreciation for the instrument but also empowers you to maintain it properly and even troubleshoot issues. This comprehensive guide breaks down the anatomy of an acoustic guitar, detailing each component from the headstock to the bridge, and explaining its role in creating the beautiful sounds we associate with acoustic music.

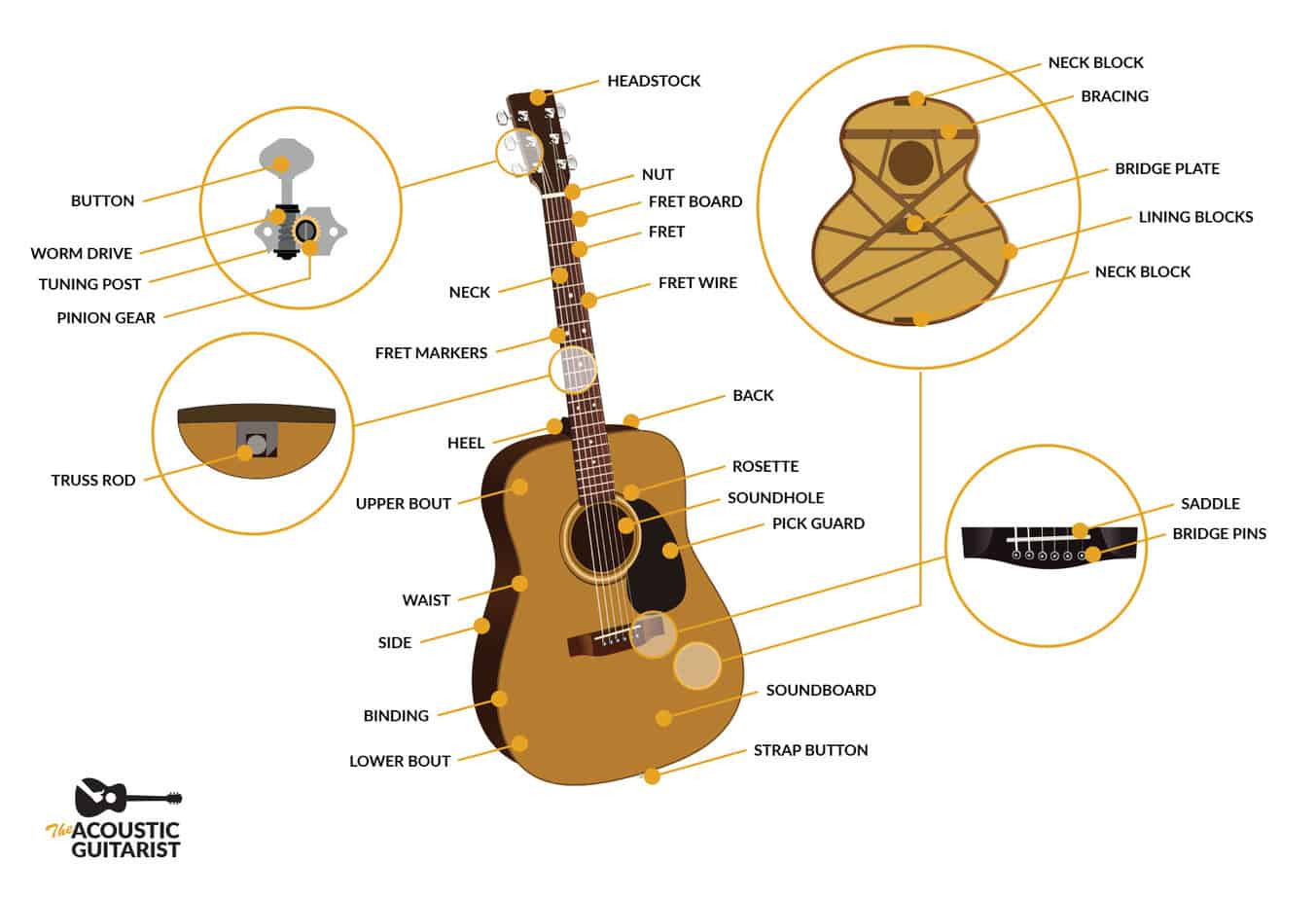

Diagram of Acoustic Guitar Anatomy

Diagram of Acoustic Guitar Anatomy

Let’s delve into the intricate details of each part that makes up this iconic instrument.

The Headstock: The Crown of the Guitar

The headstock, often referred to as the peghead, sits proudly at the very top of the guitar neck. It’s more than just a decorative element; it’s a crucial functional area housing several key components.

Its primary functions include:

- Housing the Tuning Machines: The headstock provides the anchor point for the tuning machines, the mechanisms responsible for adjusting string tension.

- String Termination Point: It serves as one of the two main points where the strings are anchored, the other being the bridge.

- Defining the Break Angle: The headstock design influences the break angle of the strings as they pass over the nut. This angle is crucial for string pressure and vibration.

- Manufacturer Branding: It’s also a prime location for displaying the guitar manufacturer’s logo, a mark of craftsmanship and identity.

Headstock designs vary, with common types including straight, tilted, and scarfed headstocks.

- Straight Headstocks: These are cost-effective to manufacture as they are crafted from a single piece of wood. However, they provide less downward pressure on the nut compared to tilted designs and are less common on high-end acoustic guitars.

- Tilted Headstocks: The most prevalent type on acoustic guitars, tilted headstocks feature an angle, typically between 9 and 15 degrees. This tilt increases the break angle over the nut, resulting in enhanced string pressure, which many believe improves sustain, clarity, and overall volume.

- Scarfed Headstocks: Similar to tilted headstocks in function, scarfed headstocks are constructed from two pieces of wood joined together. This construction method often leads to increased structural strength and stability.

Tuning Machines: Fine-Tuning Your Sound

Tuning machines, also known as tuners, tuning pegs, or machine heads, are essential for adjusting the pitch of each string. They allow guitarists to precisely tune their instrument to achieve the desired musical notes.

These mechanisms operate on a geared system. Each tuning machine consists of a cylindrical peg (tuning post) that rotates within a pinion gear. Turning the tuning peg increases or decreases the tension on the string, altering its pitch.

The gear ratio of tuning machines indicates the precision of tuning. A 12:1 gear ratio, for instance, means that twelve turns of the tuning peg result in a 360-degree rotation of the machine head cylinder. A higher gear ratio offers finer control and more precise tuning adjustments.

Tuning machines are available in two primary types:

- Sealed Gear Tuners: These are enclosed units, often favored for electric guitars due to their robustness and protection from dust and debris.

- Open Gear Tuners: Commonly found on acoustic guitars, open gear tuners have exposed gears, often giving a traditional or vintage aesthetic.

The Nut: Guiding the Strings

Positioned at the headstock end of the fretboard, the nut is a small but critically important component. Typically made from materials like hard plastic, bone, graphite, or sometimes brass, the nut plays a significant role in guitar playability and tone.

Its key functions include:

- String Spacing and Height: The nut, along with the saddle at the bridge, dictates the spacing between the strings and their height above the fretboard at the headstock end.

- Vibration Transfer: As the string’s last point of contact before the tuning machines, the nut efficiently transfers string vibrations to the guitar neck, contributing to the instrument’s overall resonance.

- Precise String Slots: Each string rests in a carefully cut slot within the nut. The depth and width of these slots are crucial for each string gauge. Slots that are too shallow can cause strings to pop out, while overly deep slots can lead to string contact with the frets, resulting in unwanted fret buzz.

- Tuning Stability: Nut slots that are too narrow can hinder the string’s ability to slide smoothly during tuning adjustments or string bending, potentially causing tuning instability.

The Neck: The Heart of Playability

The guitar neck is more than just a piece of wood; it’s the central component that dictates playability and significantly influences the instrument’s tone. It houses the headstock, tuning machines, fretboard, inlays, and strings.

Necks are attached to the guitar body in two main ways:

- Set Neck: In acoustic guitars, necks are almost always set necks, meaning they are glued to the body, creating a strong and resonant joint.

- Bolt-on Neck: While less common in acoustics, bolt-on necks are attached with screws.

Key aspects of the guitar neck include:

- Scale Length: The length of the neck directly determines the guitar’s scale length, which is the distance between the nut and the saddle. Scale length affects string tension and overall feel.

- Neck Width: The width of the neck, particularly at the nut, influences string spacing. Classical and fingerstyle guitars typically feature wider necks to provide ample space for fingerpicking. Steel-string acoustic guitars commonly have a nut width around 43mm, while classical guitars often exceed 50mm.

- Neck Profile: The shape and depth of the neck are known as the neck profile. Common profiles include C, V, and U shapes, each offering a different feel in the player’s hand.

Frets and Fret Wires: Dividing the Musical Landscape

Frets are not the metal wires themselves, but rather the spaces between the metal fret wires on the fretboard. These spaces precisely divide the fretboard into semitone intervals, enabling guitarists to play different notes and scales.

Most acoustic guitars feature between 18 and 20 frets, while electric guitars often extend to 24 or more.

Fret wires are meticulously crafted metal pieces with a distinctive “T” or mushroom shape. The top rounded part, known as the crown, is what the player’s fingers interact with, while the stem (tang) is embedded securely into the fretboard. The crown’s rounded shape ensures comfortable playability and clean note articulation.

Fret wires come in a variety of dimensions, including different heights and widths, which can affect the feel and playability of the guitar. This fret wire chart provides a detailed overview of available fret wire sizes.

Over time and with regular playing, fret wires can experience wear. This wear can lead to issues like fret buzz and require maintenance. Fret dressing is a process involving leveling and reshaping (crowning) worn frets, often performed as part of a comprehensive guitar setup to restore optimal playability.

Fret Markers / Inlays: Navigating the Fretboard

Fret markers, also known as inlays or positional markers, are visual guides embedded into the fretboard. They serve as reference points, helping guitarists quickly and accurately locate specific frets along the neck.

Inlays are typically positioned at the 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 12th, 15th, 17th, 19th, and 21st frets. The 12th fret is often marked with a double inlay, signifying the octave.

Common inlay shapes include dots, squares, and trapezoids, crafted from materials such as plastic, mother of pearl, or abalone. Classical guitars traditionally omit fretboard inlays, often relying instead on fretboard side dots, which are smaller markers placed on the side of the fretboard at the same fret positions.

Truss Rod: The Neck’s Backbone

The truss rod is a crucial component concealed within the guitar neck. It’s a metal rod that runs through the center of the neck and can be adjusted to control the neck’s relief, or bow.

The truss rod is essential for counteracting the immense tension exerted by steel strings on the neck. By adjusting the truss rod, guitarists can fine-tune the neck’s curvature to optimize playability and prevent issues like string buzz or excessively high action.

While steel-string acoustic guitars and electric guitars invariably incorporate truss rods, many classical guitars omit them. This is because nylon strings, used on classical guitars, exert significantly less tension on the neck, reducing the need for truss rod adjustments. Learn more about why classical guitars often lack truss rods.

Fretboard / Fingerboard: The Playing Surface

The fretboard, also called the fingerboard, is the thin strip of wood that is laminated onto the neck. It forms the actual playing surface where the guitarist presses down the strings to produce notes.

Common tonewoods for fretboards include Rosewood, Ebony, and Maple. Rosewood has been a traditional favorite for acoustic guitars, prized for its oily nature, which contributes to a smooth feel under the fingers and is believed to contribute to a warmer tonal character. Ebony, often favored for high-end classical guitars, is denser and offers a darker, brighter tone. Maple is more frequently seen on electric guitars, known for its bright and snappy tonal qualities.

Rosewood and CITES Regulations:

Historically, Rosewood was widely used. However, CITES restrictions (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) placed on Rosewood between 2017 and 2019 to protect Indian Rosewood, prompted the industry to explore alternative materials, including engineered timbers.

Update: The CITES regulations have since been updated. As of 2019, finished musical instruments, parts, and accessories are exempt from restrictions for all rosewood species, except for Brazilian rosewood, which remains protected.

Heel / Neck Joint: Where Neck Meets Body

The heel, or neck joint, is the point where the guitar neck seamlessly joins the body, connecting to the guitar’s sides.

For acoustic guitars, this joint is almost universally a glued joint, often employing a dovetail joint. Dovetail joints are renowned for their strength and resonance transfer and have been a hallmark of acoustic guitar construction for centuries.

Acoustic guitar necks typically join the body at the 14th fret. However, smaller-bodied “parlor” guitars, also known as 12-fret guitars, feature a neck joint at the 12th fret, altering their tonal characteristics and playability.

Back and Sides: Shaping the Resonance Chamber

The back and sides of an acoustic guitar are crucial components that form the resonant chamber of the instrument. They are typically constructed from matched sets of tonewoods. Rosewood back and sides, for example, are frequently paired with Sitka or Adirondack Spruce tops, creating a classic tonal combination.

While the soundboard (top) is primarily responsible for projecting sound due to its flexibility, the back and sides contribute significantly to the guitar’s overall tone and stability. They reflect and shape the sound waves within the guitar body, influencing its tonal color and resonance. Explore how different back and sides woods affect guitar tone.

Lower Bout, Waist, and Upper Bout: The Guitar’s Form

Acoustic guitar bodies are characterized by their distinctive shape, comprising three main sections:

- Upper Bout: The top half of the guitar body.

- Lower Bout: The larger bottom half of the guitar body.

- Waist: The narrower section that connects the upper and lower bouts.

The body shape is not merely aesthetic; it significantly influences both the playability and tonal characteristics of the guitar. The shape affects how comfortably the guitar sits against the player’s body and, more importantly, how sound waves resonate within the instrument’s body.

The body shape and size directly impact the guitar’s internal air resonance. For example, a wider lower bout tends to lower the air resonance frequency, enhancing the definition and depth of the guitar’s bass frequencies.

* It’s important to remember that body shape is just one of many factors contributing to a guitar’s overall tone.

Sound Hole: Projecting the Voice

The soundhole is the opening in the guitar’s soundboard, serving as the primary outlet for the sound generated within the guitar body.

In most acoustic guitars, the soundhole is circular. However, variations exist, such as F-holes, commonly seen on jazz-style acoustic and electric guitars. Gypsy guitars (Selmer guitars) often feature elongated soundholes, while some luthiers, like Bourgeois and Martin on select models, utilize larger-than-standard soundholes.

Contrary to a common misconception, the soundhole itself isn’t the origin of the guitar’s sound. The sound originates from the vibration of the soundboard. However, the soundhole is essential as it allows the internal air resonance to escape and project outwards, making the sound audible.

Covering the soundhole, for instance with a soundhole cover to reduce feedback, does not drastically reduce the guitar’s volume. However, dampening the internal cavity of the guitar, such as with a towel, significantly diminishes volume by restricting the soundboard’s vibration and resonance.

Rosette: Decorative and Functional Ring

The rosette is the decorative ring that encircles the soundhole. While visually appealing, the rosette also serves a practical purpose.

It reinforces the wood around the soundhole, which is a vulnerable area prone to moisture absorption and cracking. The rosette adds structural integrity, helping to prevent damage and maintain the soundboard’s integrity over time.

Pickguard / Scratch Plate: Protecting the Finish

The pickguard, also known as a scratchplate, is a protective layer adhered to the guitar’s body, typically below the soundhole. Its primary function is to shield the delicate soundboard from scratches and wear caused by guitar picks or fingernails during strumming and playing.

Pickguards are usually constructed from laminated plastic, often in three-ply configurations, and come in various shapes and styles to complement the guitar’s aesthetics.

Classical guitars typically do not feature pickguards, as classical guitarists generally play fingerstyle. However, flamenco guitars often incorporate a clear protective plate called a golpeador in place of a pickguard. The golpeador is designed to withstand the more percussive and aggressive strumming techniques characteristic of flamenco music, protecting the soundboard from damage. Learn more about the flamenco guitar golpeador.

Binding: Edging and Elegance

Binding refers to the decorative and protective strip that runs along the edges of the guitar, typically where the top and sides join. Binding can also be found on the back of the guitar and along the neck (in which case it’s called a bound neck). Materials used for binding include vinyl, PVC plastic, wood, and others.

Binding serves multiple purposes:

- Decoration: It adds an aesthetic touch, creating a visually appealing transition between the different sections of the guitar body.

- Protection: Binding protects the edges of the guitar, which are particularly vulnerable to impacts and damage.

- Playing Comfort: Neck binding can enhance playing comfort by providing a smoother edge along the fretboard.

Explore more about guitar binding and its uses.

Soundboard: The Soul of the Acoustic Guitar

The soundboard, or top, is arguably the most critical component in the acoustic guitar’s anatomy. It’s the large, resonant surface that houses the bridge and soundhole and is responsible for the majority of the guitar’s acoustic projection.

Acoustic guitars rely on resonance to produce sound. The soundboard vibrates in response to string vibrations transmitted through the bridge and saddle. This vibration of the soundboard creates sound waves that are projected outwards through the soundhole.

The choice of tonewood for the soundboard is paramount in determining an acoustic guitar’s tonal characteristics, resonance, and volume. Woods like Spruce (Sitka, Adirondack), Cedar, and Mahogany are commonly used, each offering unique tonal properties. The soundboard wood must be both strong and lightweight to vibrate freely while withstanding the tension of the strings.

To further enhance strength and control vibration, soundboards incorporate bracing, a system of internal wooden supports.

Bridge, Saddle, and Bridge Pins: String Anchors and Tone Transfer

The bridge is the anchor point for the strings on the guitar body. It’s a carefully designed component that not only secures the strings but also facilitates the transfer of string vibrations to the soundboard.

Strings are typically threaded through small holes in the bridge and secured by bridge pins (also called fixing pegs). These pins are inserted into string holes on the bridge, firmly holding the strings in place. Learn how to prevent bridge pins from popping out.

The bridge also houses the saddle, a thin strip of material, often bone, plastic, or synthetic material, upon which the strings rest. The saddle is crucial for setting the string height (action) and intonation.

Unlike the nut, the saddle is usually angled, with the bass string side slightly further back. This angled positioning is essential for accurate intonation. Thicker bass strings require a slightly longer vibrating length to compensate for their mass and tension when fretted.

Bracing: The Internal Framework

Bracing refers to the internal network of wooden struts that reinforce the guitar’s top (soundboard) and back. These struts are typically made from lightweight yet strong woods like Spruce.

Bracing provides essential structural support to the large, thin panels of the soundboard and back, preventing them from warping or collapsing under string tension. At the same time, bracing is carefully designed to be lightweight to minimize any damping effect on the guitar’s resonance.

Some bracing struts are scalloped, a technique involving carving away wood to further reduce weight while maintaining structural integrity.

Different bracing patterns exist, each influencing the guitar’s tone and responsiveness. X-bracing is the most common pattern for steel-string guitars, known for its balance of strength and resonance. Classical guitars commonly employ fan bracing. Guitar backs often utilize ladder bracing, a simpler pattern with struts running perpendicular to the strings.

Ladder Bracing on a Guitar Back

Ladder Bracing on a Guitar Back

Conclusion: A Symphony of Parts

The acoustic guitar is a marvel of engineering and craftsmanship, a harmonious assembly of carefully designed parts working in concert to produce music. From the headstock to the bridge, each component plays a vital role in shaping the instrument’s sound, playability, and overall character. Understanding the anatomy of your acoustic guitar deepens your connection with the instrument and empowers you to appreciate its intricacies and maintain it for years of musical enjoyment.

The subtle variations in materials, construction techniques, and design across different guitar models are what give each acoustic guitar its unique voice and suitability for various musical styles. This explains why many guitarists find that owning just one guitar is never quite enough!

If you found this exploration of Acoustic Guitar Anatomy insightful, you might also enjoy reading about why acoustic guitars sound better with age.

Explore Further

How Back & Sides of Guitars Influence Tone

Discover how the choice of wood for the back and sides of an acoustic guitar significantly shapes its tonal character and resonance.

Read Article

Are Acoustic Guitars Harder to Play?

Are Acoustic Guitars Harder to Play?

Are Acoustic Guitars Really Harder to Play Than Electric?

Uncover the reasons why acoustic guitars can feel more physically demanding to play than electric guitars, and what factors to consider when choosing your first instrument.

Read Article

Guitar Binding

Guitar Binding

What is Guitar Binding (And Why We Use It)

Learn all about guitar binding, its materials, its decorative role, and its protective function in acoustic guitar construction.

Read Article