Guitar chord theory can initially seem daunting, even for seasoned players. Many guitarists, especially those focused on playing, might shy away from diving into the theoretical underpinnings of chords. For a long time, I, too, prioritized learning lead techniques, emulating guitar heroes, and neglected the crucial world of chords and rhythm guitar. Hours were spent mastering licks, but basic chord knowledge remained underdeveloped.

However, recognizing this gap, I dedicated myself to understanding guitar chords and their theory. This journey has profoundly impacted my playing. My comfort and confidence in navigating chords across the fretboard have soared, and surprisingly, my lead guitar skills have also seen significant improvement.

Why? Because chords are the bedrock of almost all music. Solos are, in most cases, played over a chord progression. Even if your passion lies solely in lead guitar, grasping chord construction and function is invaluable.

Understanding chords will empower you to craft more nuanced and sophisticated solos. It allows you to interact musically with the underlying harmony, creating solos that are melodic and deeply integrated with the music, rather than just sitting on top of it.

Furthermore, if songwriting is on your horizon, even a basic understanding of guitar chord theory is essential. It provides the tools to build compelling and effective chord progressions that truly capture your musical vision.

Guitar chord theory is vast, extending far beyond a single article. Therefore, this guide focuses on the fundamentals, giving you the bedrock knowledge to understand and become comfortable with major guitar chords and their construction. This foundational knowledge will be your stepping stone to deeper theoretical explorations.

In this article, we will explore:

It’s important to note that this article is primarily focused on theory, not a collection of chord diagrams for immediate playing. Practical chord shapes and applications will be covered in future articles.

The knowledge presented here is designed to make learning and utilizing chords significantly easier in the long run. Whether your goal is to enhance rhythm guitar skills, write original music, or simply evolve as a well-rounded musician, this guide to major guitar chords will provide valuable insights. Let’s delve into the basics of guitar chord theory, starting with the major scale.

The Indispensable Major Scale

To truly understand major guitar chords and how all guitar chords are formed, we must first understand the major scale. It might not immediately seem relevant, but the major scale is the cornerstone of Western music theory, including blues and countless other genres. It’s within the framework of the major scale that the logic of chord construction begins to reveal itself.

If you’re unfamiliar with the major scale, it’s recommended to first read a dedicated resource on ‘Getting Started With The Major Scale’ to grasp its shapes and intricacies.

In brief, the major scale is a seven-note scale. Every musical scale has a formula, and the major scale formula is:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|

These numbers represent the degrees within the major scale. ‘1’ is the root note, ‘2’ the second, and so on. In the key of C major, the notes are:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|

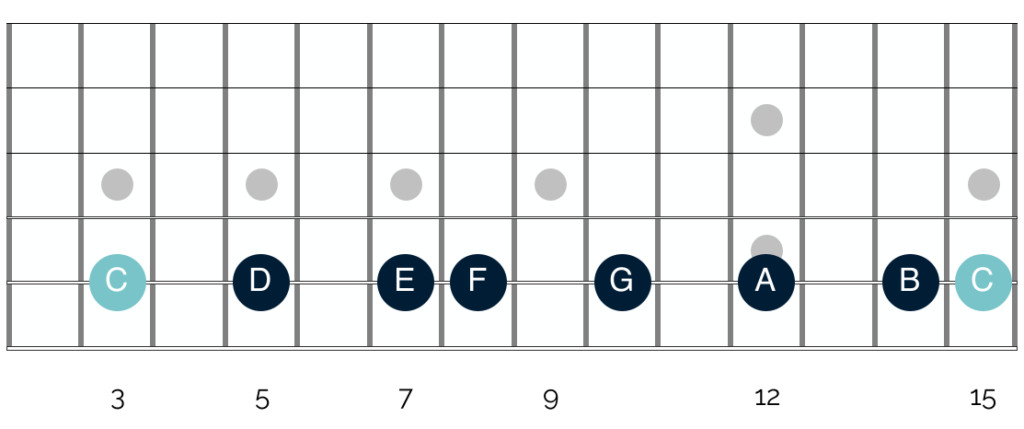

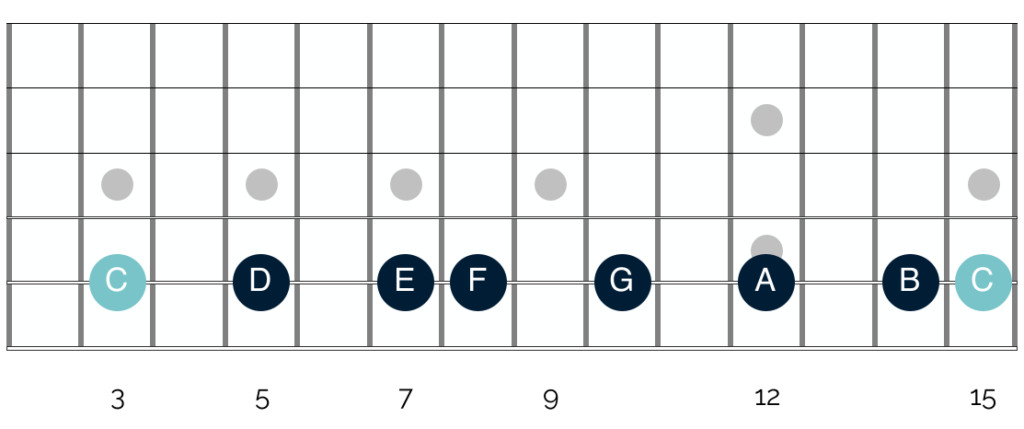

Visually, the C major scale across the fretboard looks like this:

Understanding the major scale is the first step to understanding guitar chord theory

Understanding the major scale is the first step to understanding guitar chord theory

In music theory, a chord is defined as a combination of at least three notes played simultaneously. Therefore, to construct a chord, we need to “stack” at least three notes from the major scale. However, chord creation isn’t arbitrary. There’s a specific logic to it, and while it might initially seem complex, understanding this logic unlocks a much deeper and more intuitive understanding of chords. This understanding is key to mastering A Major Guitar Chord.

Building Triads: The Foundation of Major Chords

The specific notes you choose to stack, their quantity, and their stacking order determine the type of chord formed. We’ll explore these nuances later. First, let’s focus on basic chord construction.

The simplest chord form is a triad – a three-note chord. Triads are built using notes that are a third apart. This refers to the interval of a third. If intervals are new to you, it’s beneficial to explore an article dedicated to guitar intervals before proceeding.

Let’s revisit the C major scale:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

The highlighted notes (C, E, G) form a C major triad. These three notes are each separated by a third. The term “third” might be initially confusing. While C and E are separated by only one scale note (D), and E and G are also separated by one scale note (F), the “third” is counted inclusively.

Starting from C, D is the second note, and E is the third. Similarly, from E, F is the second, and G is the third.

Think of it as skipping every other note in the scale. Play C, skip D, play E, skip F, play G, and so forth.

That’s the essence of triad formation! Select three notes from the major scale, each a third apart, play them together, and you have a chord. In this case, you’ve created a major guitar chord triad.

Intervals: The Secret Ingredient in Major Chords

Now, the concept becomes slightly more intricate as we consider different starting notes within the major scale. While starting on C and building a triad resulted in a C major triad, this isn’t the case for every note in the scale. This difference arises due to intervals.

As mentioned, a triad is formed by stacking three notes, each a third apart. However, the quality of these “thirds,” the specific intervals between the notes, dictates the final chord type.

If you are familiar with the major scale, you’ll know that the intervals between its notes are not uniform. This is visually clear when we look at the scale on the fretboard:

Understanding the major scale is the first step to understanding guitar chord theory

Understanding the major scale is the first step to understanding guitar chord theory

Notice the varying fret distances between notes. Some are separated by two frets, others by just one. This is crucial when building triads from different scale degrees. Even though the notes in each triad are a “third” apart in scale degrees, the actual musical intervals between them change based on the starting note.

Let’s compare a triad starting on C with one starting on D:

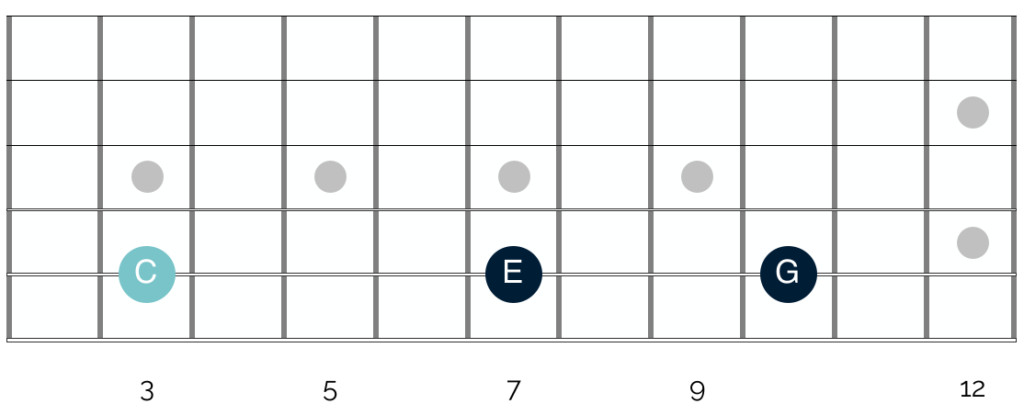

C major triad intervals on guitar fretboard

C major triad intervals on guitar fretboard

In the first diagram, the root note is C (light blue). There are four frets between C and E, and three frets between E and G. Between C and G, there are seven frets.

Each fret equals a semitone. Thus, C to E is two whole tones, E to G is one and a half tones, and C to G is three and a half tones.

Now compare this to a triad starting on D:

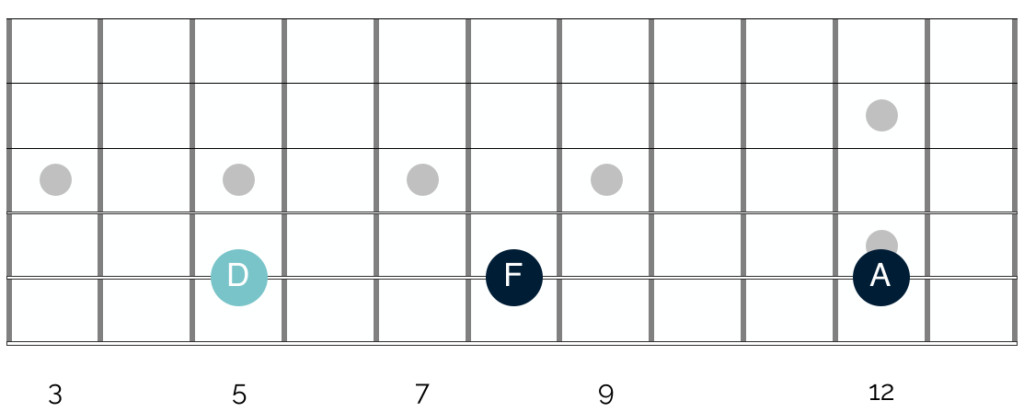

D minor triad intervals on guitar fretboard

D minor triad intervals on guitar fretboard

Here, the intervals are different. Between D and F, there are only three frets (one and a half tones). Between F and A, there are four frets (two tones). However, like the C triad, the distance from the root (D) to the highest note (A) remains seven frets, or three and a half tones.

Playing these notes simultaneously results in a C major triad and a D minor triad.

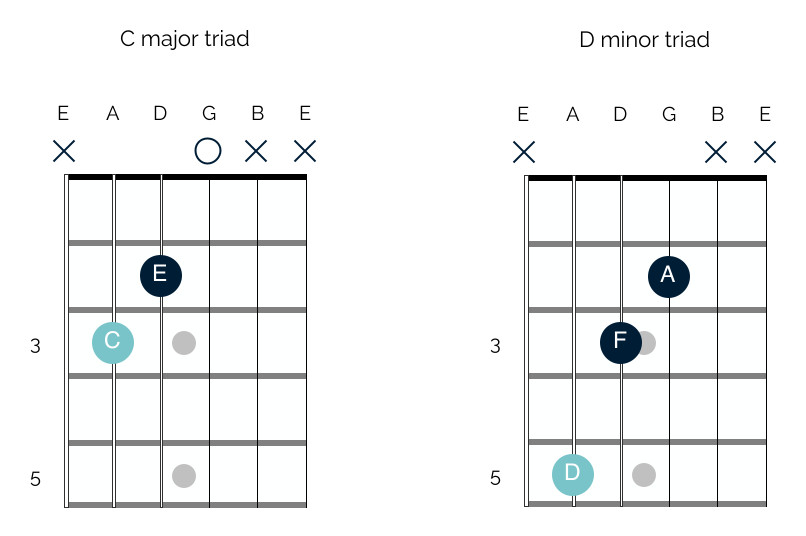

C major and D minor chord diagrams

C major and D minor chord diagrams

The C major triad utilizes open strings. Notice that the G note is played on the open G string instead of fretted.

Before delving into the theory behind major and minor qualities, play both triads. Listen to the contrasting sounds. The major triad sounds bright and happy, while the minor triad has a more somber, melancholic feel. This difference in sound stems from the varying intervals within each triad, a fundamental concept in guitar chord theory and especially understanding a major guitar chord.

Major & Minor Triads: Defining the Sound

As we saw, a triad built on C in the key of C major is a C major triad. Building a triad on D results in a D minor triad. Let’s visualize these triads again with their intervals:

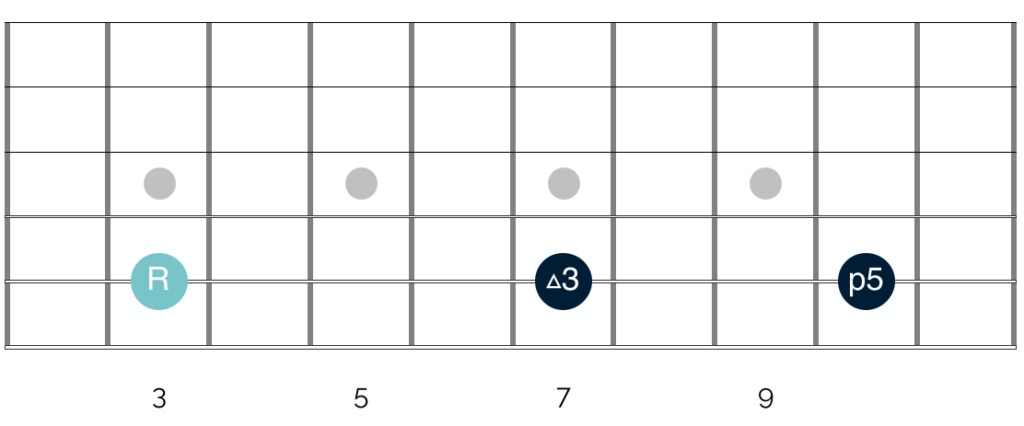

C major triad intervals labeled

C major triad intervals labeled

This diagram shows the intervals, not just note names. The intervals in a major triad are:

- Root

- Major third

- Perfect fifth

The first note is always the root, defining the chord’s name (C for C major).

A major third is always four frets (two whole tones) above the root. This major interval gives the chord its major quality – its bright, happy sound.

A perfect fifth is always seven frets (three and a half tones) above the root. Perfect intervals are associated with consonance and resolution, lending the chord stability and a harmonious, tension-free quality.

Now, let’s compare these intervals to the D minor triad:

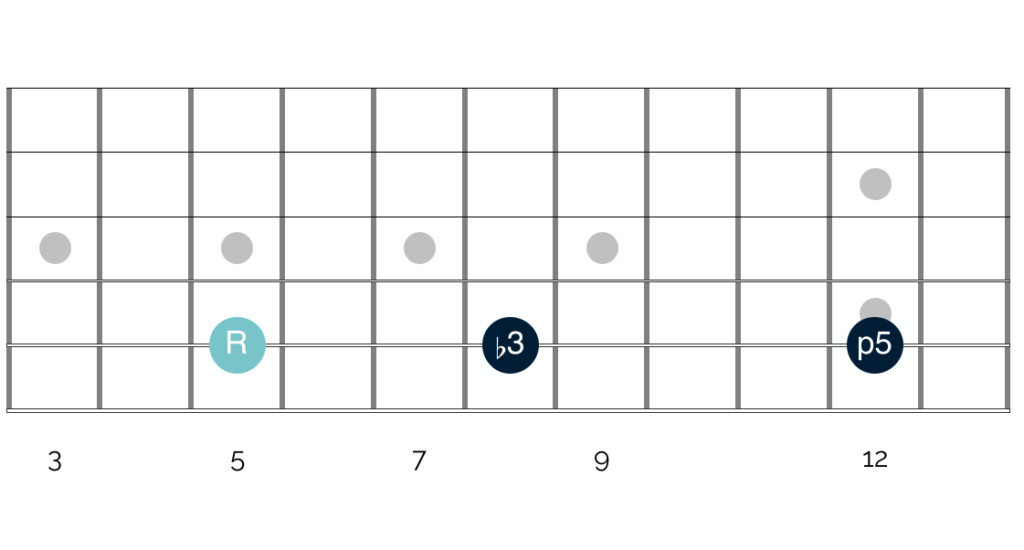

D minor triad intervals labeled

D minor triad intervals labeled

Again, we see the intervals, not note names. The intervals in a minor triad are:

- Root

- Minor third

- Perfect fifth

Like the major triad, the minor triad has a root (D) and a perfect fifth. The key difference is the minor third instead of a major third.

A minor third is always one fret lower than a major third, and one and a half tones above the root. This minor interval gives the chord its minor quality, resulting in its sad or melancholic sound.

Crucially, both major and minor triads contain a perfect fifth, contributing to their stable and resolved sound, even though minor chords have a more downbeat character.

Harmonizing the Major Scale: Unveiling Chord Patterns

The next step in understanding guitar chord theory, especially regarding a major guitar chord and its counterparts, is to apply triad construction to every note of the major scale. This reveals the inherent relationship between scale notes and the chords they form.

Let’s return to the C major scale notes:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Starting on C, build a triad by selecting every other note (C, E, G). Repeat this for D, E, and so on. For F and subsequent notes, continue the same pattern, cycling back to the beginning of the scale when needed. For example, for F, the triad notes are F, A, and C; for G, they are G, B, and D.

Remember these key interval distances:

- Major third: 4 frets above the root – creates a major triad.

- Minor third: 3 frets above the root – creates a minor triad.

- Perfect fifth: 7 frets above the root.

By harmonizing the major scale, you’ll discover two significant patterns. First, you’ll create a combination of both major and minor triads. Second, the triad built on the 7th scale degree will sound distinct from both major and minor triads. Let’s see the results:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes in triad | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Type of triad | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

Harmonizing any major scale produces this same pattern: three major triads, three minor triads, and one diminished triad. The specific chords change depending on the key, but the major/minor/diminished sequence remains constant across all major scales.

This pattern is fundamental to music composition, as musicians use these chord sequences to create chord progressions. We’ll explore this further. But first, let’s examine the unique diminished triad formed on the 7th degree of the major scale.

Diminished Triads: A Different Flavor

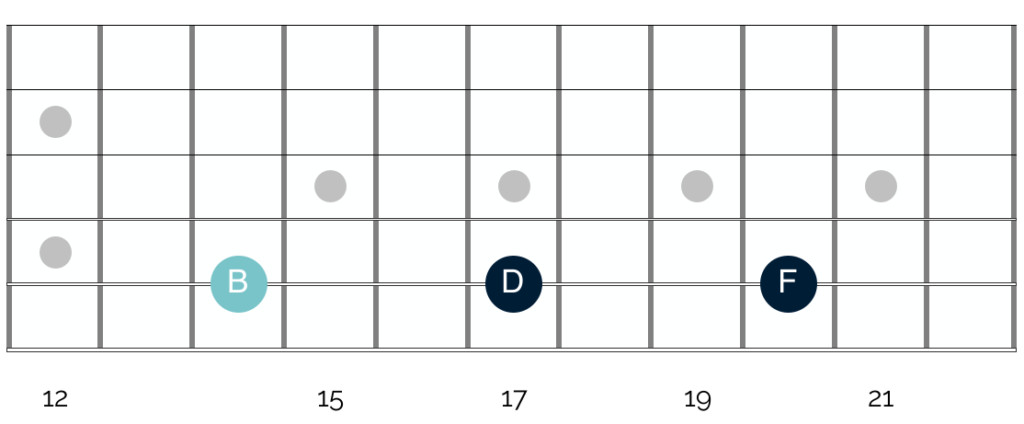

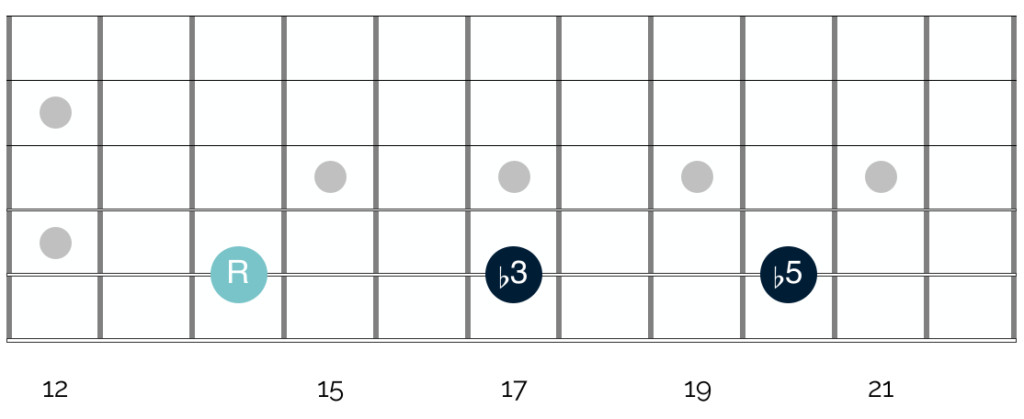

As you harmonize the major scale, you’ll notice the triad on the 7th degree is different. Let’s visualize its notes on the fretboard:

Diminished triad notes on guitar fretboard

Diminished triad notes on guitar fretboard

The triad construction is the same – three notes a third apart in the scale. So, why is it diminished instead of major or minor? The answer lies in the intervals:

Diminished triad intervals labeled

Diminished triad intervals labeled

The intervals are:

- Root

- Minor third

- Flat fifth

The root and minor third are the same as in minor triads. The crucial difference is the flat fifth. Instead of a perfect fifth (7 frets), there are only six frets between the root (B) and the top note (F).

This diminished fifth interval is tense, dissonant, and unresolved, giving diminished chords their characteristic sound. Diminished chords are less common than major and minor chords but still play a vital role in adding harmonic color and tension in music.

Triads & Chords: Bridging Theory to Practice

At this point, you might be wondering how to apply this theoretical knowledge practically. While understanding triads is essential for guitar chord theory, we need to connect this to actual playing. The term “triad” is more common in theoretical discussions, while guitarists often use the term “chord.” Let’s clarify the relationship between them.

As stated earlier, a triad is a three-note chord built in thirds. Therefore, all triads are chords, but not all chords are triads. However, in practice, you’re not limited to only playing three notes when using a triad concept.

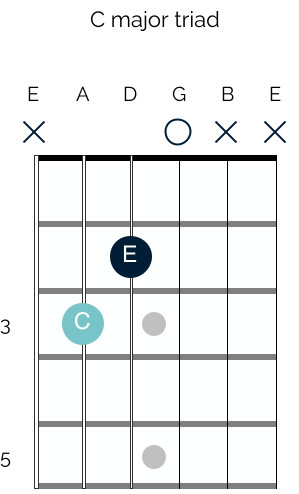

Consider the C major triad again:

C major triad diagram (3 notes)

C major triad diagram (3 notes)

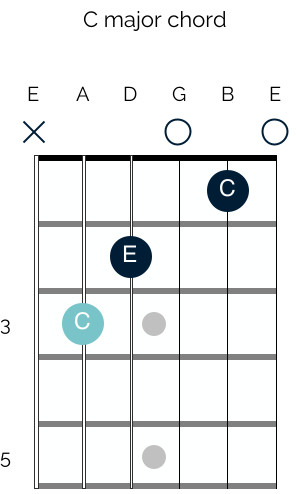

This diagram shows the pure three-note triad. But you’re likely more familiar with this C major chord shape:

C major chord diagram (full chord)

C major chord diagram (full chord)

Calling the first diagram a “C major triad” and the second a “C major chord” can be misleading. The terms are often used interchangeably because both contain the same unique notes: C, E, and G.

The “full” C major chord simply repeats some of these notes across different octaves. It’s still a C major triad at its core because it only contains the three unique notes of the C major triad: C, E, and G. This applies to most basic major and minor chords you already know.

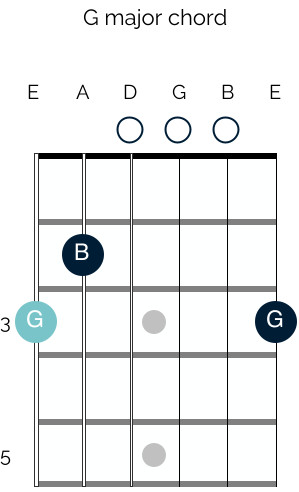

Let’s look at G major. The G major triad notes are G, B, and D. A “pure” G major triad can be played like this:

G major triad diagram (3 notes)

G major triad diagram (3 notes)

Here, the triad is played on the 6th, 5th, and 4th strings. But a full G major chord, played across all six strings, still uses only the G, B, and D notes, just repeated in different octaves.

Crafting Chord Progressions with Major Chords and Beyond

Understanding that familiar major and minor chords are based on triads bridges the gap between theory and practical playing. Now, we can use this knowledge to build chord progressions.

Let’s revisit the harmonized major scale table:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes in triad | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Type of triad | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Chord | C Major | D Minor | E Minor | F Major | G Major | A Minor | B Diminished |

| Triad / chord number | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii° |

This table now includes Roman numerals assigning numbers to each triad, just like scale degrees. Uppercase numerals denote major triads, lowercase for minor, and lowercase with a “°” for diminished.

Musicians use these chords to create progressions. Songs in C major often use chords from this table. The Beatles’ “Let It Be” in C major uses C major, G major, A minor, and F major – the I, V, vi, and IV chords.

Guitarists use Roman numerals to discuss chord progressions. A “one, four, five” progression refers to the I, IV, and V chords of a key. In C major, this would be C major, F major, and G major. Understanding these numerals allows you to quickly grasp and communicate chord progressions in any key.

Stepping Beyond Basic Chord Theory

Chord progressions are not always strictly derived from a single major scale. Musicians often deviate from diatonic harmony for creative effect.

Firstly, songs rarely use chords only from one major scale. Songwriters might change keys or “borrow” chords from other keys to create harmonic interest. While understanding major scale harmonization is foundational, exploring chord borrowing and key changes is crucial for deeper analysis.

Secondly, guitarists often add “chord extensions” to basic triads. These extensions, like 7ths, 9ths, etc., don’t change the fundamental major or minor quality but add color and complexity. Major 7th, minor 7th, and dominant 7th chords are ubiquitous in popular music. Understanding basic triad theory makes learning chord extensions much more accessible.

While these advanced topics are beyond this introductory article, they are logical next steps. For now, focus on mastering the guitar chord theory presented here. It’s complex and requires time and practice. Don’t be discouraged if it’s initially challenging. Revisit this material, apply it to your guitar, and with persistence, it will become clear.

Good luck, and feel free to reach out with any questions!

References & Images

Unsplash, Guitar Habits, Wikipedia, Hello Music Theory, Music Notes Now, Wikipedia, Puget Sound, Open Music Theory, Guitar Theory For Dummies, Modern Music Theory For Guitarists