Poison Ivy Rorschach, the legendary guitarist for The Cramps, famously lamented, “Nobody ever talks to me about music or guitar.” For a musician who crafted such a distinctive and influential sound, her frustration was understandable. While the spotlight often fixated on Lux Interior’s wild stage presence, it was Poison Ivy’s guitar that was the true engine of The Cramps’ unique brand of punk-infused rockabilly. Her playing, a blend of raw punk energy and vintage rock and roll swagger, was as integral to The Cramps’ identity as Lux’s theatrical antics. It’s time to give Poison Ivy and her guitar the recognition they deserve.

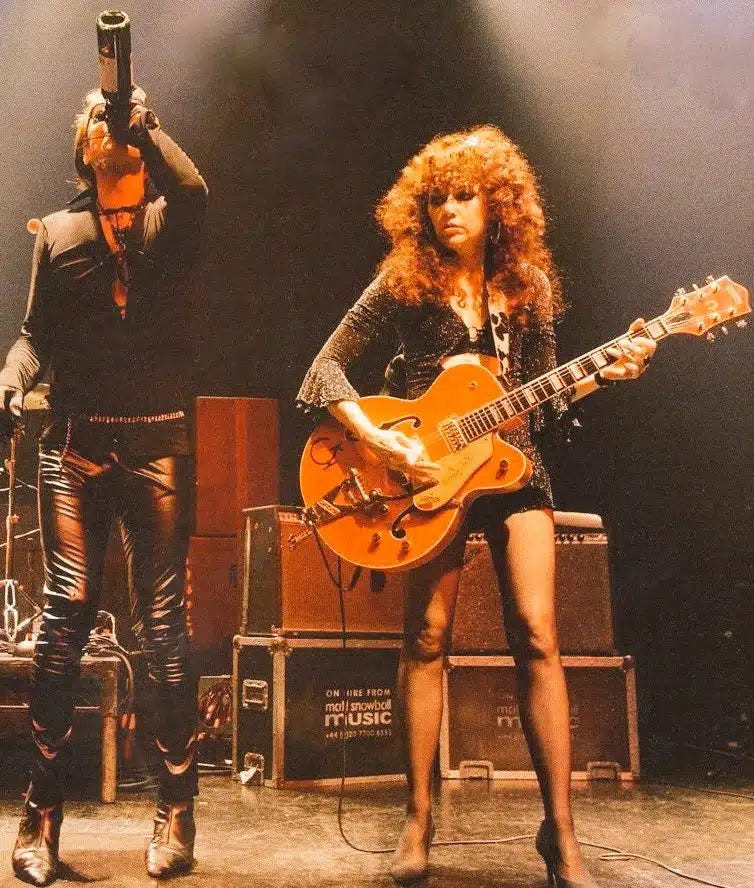

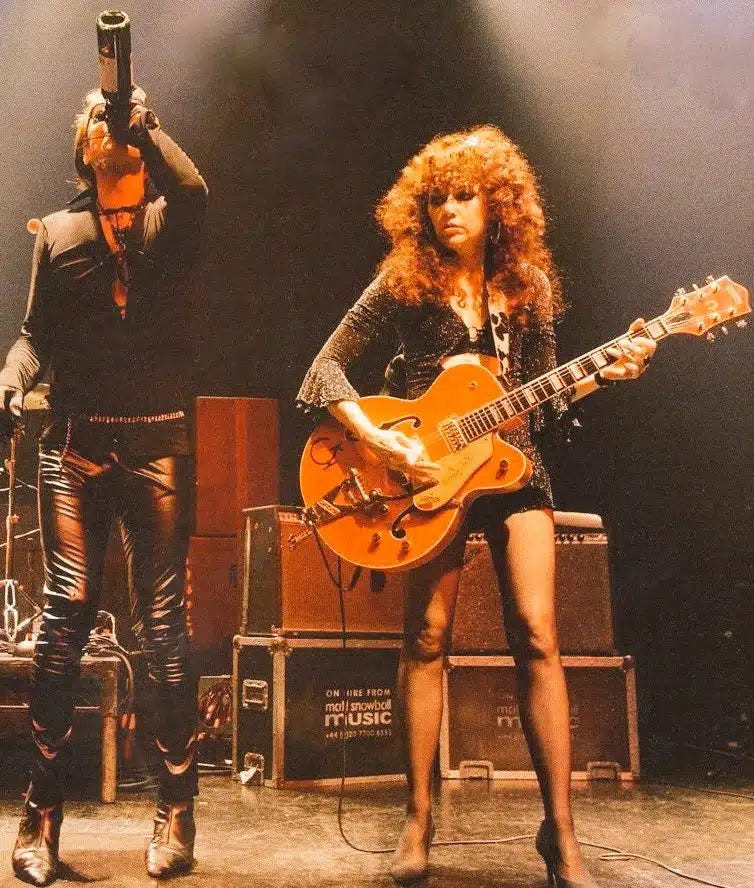

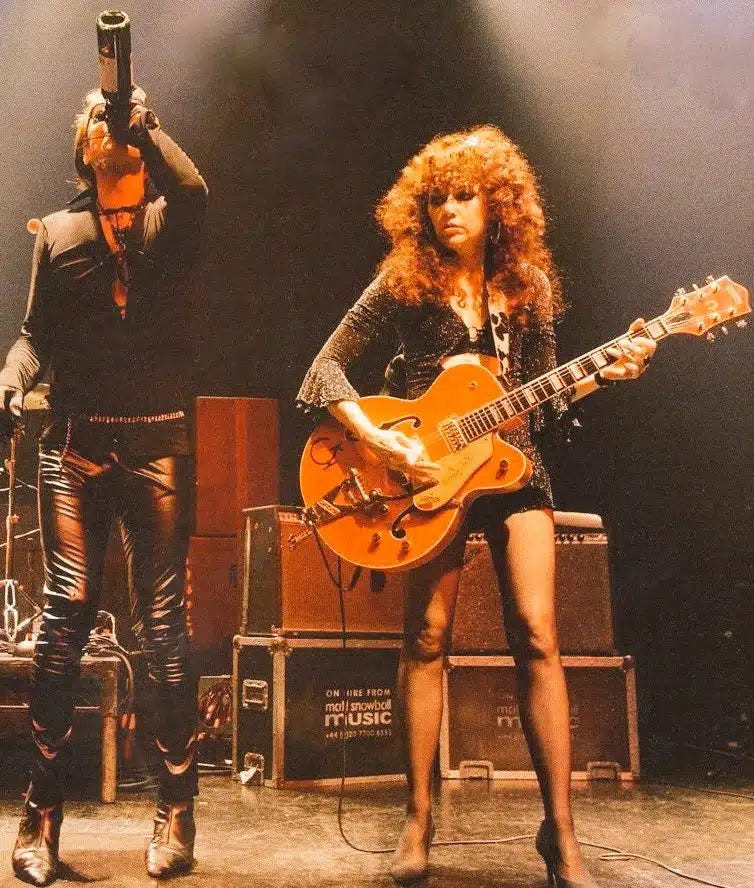

Often overshadowed by the flamboyant frontman Lux Interior, Poison Ivy, born Kristy Marlana Wallace, was the musical mastermind behind The Cramps. While Lux writhed and howled, captivating audiences with his chaotic energy, Ivy remained cool and collected, delivering razor-sharp guitar riffs that defined the band’s sound. This dynamic, reminiscent of Keely Smith’s poised artistry alongside Louis Prima’s boisterous showmanship, highlighted Ivy’s essential role. She was not just a guitarist; she was the band’s architect, her guitar work the foundation upon which their sonic mayhem was built.

Like Lux, Poison Ivy’s musical tastes were deeply rooted in the fringes of American music and culture. They shared a fascination with ’60s garage rock, the raw energy of Sun Records, and the lurid allure of pulp fiction and B-movies. These shared obsessions formed the bedrock of The Cramps’ aesthetic. While punk provided the attitude and energy, rockabilly was the core ingredient in their musical concoction. This rockabilly foundation, seasoned with garage rock grit and horror-movie camp, remained remarkably consistent throughout their 30-year career, evolving only slightly with the addition of bass in the early 80s.

[

The duo’s ambition upon relocating from Akron, Ohio to New York City was bold: to become the new New York Dolls, as Lux stated. They admired the Dolls’ glamor, two-guitar attack, and R&B influences, but felt something crucial was missing. They believed that rockabilly, a potent and often overlooked force, was the “deadly ingredient” that could elevate their sound beyond their predecessors, from the early Rolling Stones to T. Rex. This vision set them apart, driving them to forge a sound that was both retro and fiercely modern.

In the gritty environment of 1970s New York City, Poison Ivy and Lux solidified their vision. Working unconventional jobs – Lux as a record store clerk and Ivy reportedly as a dominatrix – they immersed themselves in the city’s underground scene. Together with guitarist Bryan Gregory and a rotating cast of drummers including Miriam Linna and Nick Knox, they began crafting their signature sound: a mutant blend of New York Dolls-esque garage rock and raw rockabilly, spearheaded by Ivy’s distinctive guitar playing. Bryan Gregory’s pockmarked, fuzz-toned guitar added to the band’s raw edge, but it was Ivy who became the band’s musical director, steering their sonic direction from the start. Her leadership extended beyond songwriting; she eventually took on production and management duties, becoming the undeniable driving force behind The Cramps.

Kid Congo Powers, who later replaced Gregory, described the band’s dynamic vividly: “If something bad [happened], Ivy would snap her fingers and point and we’d have to beat someone up. It was like being in a gang – like a juvenile delinquent band – and it was great.” This anecdote underscores Ivy’s authority and the band’s rebellious spirit, qualities that were mirrored in their music. Her control extended even to dictating musical boundaries, famously banning Chuck Berry riffs from their repertoire.

[

Ivy explained this seemingly paradoxical rule: “We loved Chuck Berry, but we had a rule that we wouldn’t do Chuck Berry licks. All rock ’n’ roll from the ’60s, going into the ’70s, was based on Chuck Berry, at the exclusion of any other influence. So even though we loved Chuck, we decided to do all we could to not have that influence. There was too much, y’know?” Her point was sharp: while acknowledging Berry’s monumental status, she sought to explore the less-charted territories of rock and roll guitar, deliberately avoiding well-trodden paths.

She observed the pervasive influence of Chuck Berry, even in punk, often overshadowing other pivotal figures like Johnny Thunders. “Yeah, and it’s astounding,” she agreed. “You never would hear Link Wray influences or Duane Eddy. We couldn’t figure it out because it was pure rock ’n’ roll. It’s as monumental as Chuck Berry, and for it to be ignored seemed strange.” This observation highlights her commitment to uncovering and celebrating rock and roll’s overlooked pioneers, and consciously integrating their styles into her own playing.

Ivy articulated the distinct guitar styles of Link Wray and Duane Eddy, emphasizing their unique contributions to rock and roll guitar. “Link Wray is all about The Chord,” she stated. “A monumental chord and the drama of it. It’s very haunting, stark. He had that thing I call ‘the grind’ – that really fast, grinding, dead strumming. With Link Wray it’s about the chords and the drama. It sounds dangerous to me, it sounds spooky.” She contrasted Wray’s chord-centric, dramatic style with Duane Eddy’s approach: “With Duane Eddy, it’s all about The Note — a single note, just the ultimate twang. Duane Eddy also sounds spooky. They both have drama. He had those backing vocals that sound like they’re ghosts, y’know, from hell.” These analyses reveal Ivy’s deep understanding of guitar styles and her appreciation for the nuances within rock and roll’s DNA.

She further elaborated on Eddy’s early sound: “His early stuff like ‘Ramrod’ and ‘Stalkin’’ was just rough, dangerous hoodlum music. That’s who bought that stuff.” She also expressed admiration for Ike Turner’s innovative guitar work: “Another guitarist I love is Ike Turner. He produced a lot, and he considered himself more of a piano player, but his guitar playing was totally unique. He must’ve got a Stratocaster the day it came out, and he went nuts with the vibrato bar. It’s insane. If you see pictures, he has these really long fingers and huge hands wrapped around a skinny Stratocaster neck.” These influences – Wray, Eddy, and Turner – are all audible in Ivy’s playing, fused into a style that was uniquely her own within The Cramps’ soundscape.

While Lux Interior was the visible embodiment of The Cramps’ outrageous persona, Poison Ivy was the band’s sonic architect. Her guitar playing was a potent mix: the raw, abrasive energy of punk colliding head-on with the untamed spirit of rockabilly’s early days. It was a sonic shot of adrenaline – raw, unfiltered, and delivered with a heavy dose of fuzz, reverb, and tremolo. This signature sound propelled iconic Cramps tracks like “I Was A Teenage Werewolf,” a song that cleverly used the B-movie trope to explore teenage angst with lyrics like, “You know, I have puberty rights/And I have puberty wrongs/No one understood me/All my teeth were so long.” Later, her guitar provided the seductive undercurrent for their explorations of sexuality, as heard in tracks like “My bird can do the dog/If your pussy can.”

[

Poison Ivy’s choice of equipment further underscored her dedication to rock and roll’s roots while rejecting clichés. Eschewing mainstream guitars like Les Pauls or Stratocasters, she initially favored rare Canadian-made Lewis guitars. As she recounted to Vintage Guitar, “I had this kind of rare Canadian guitar called Lewis. Actually, I had two of them. I bought the first on 48th Street in New York City in 1976, then the second in Vancouver in 1983. They’re both solidbodies with a Bigsby-like vibrato bar, and they both weigh a ton. One unusual characteristic about both of them is that the necks are flat and wide, like a classical guitar.” These unusual guitars contributed to her distinctive tone in the early Cramps years.

She transitioned to her iconic Gretsch after a mishap with her Lewis guitar: “That’s when I got my Gretsch, and I never turned back. That was ’85. I got a 1958 Gretsch 6120 and there’s just no going back. I’ve got other guitars including a Gibson ES-295 and some guitars I almost never touch. I have a Telecaster that I love. It’s great, but it’s just not my style. The Gretsch is my ultimate style. I have a 6120 reissue as a backup, for when I break a string. But the original Gretsch is my main guitar, and that’s all I play. It weighs a ton and I have heavy gauge strings on it, so it’s a struggle. But it just sounds so damn good! I hesitate to take it out because it’s worth more than the reissues, but I just can’t get that sound with anything else. I’m too attached to it and it just kind of responds to me.” Her deep connection with her vintage Gretsch 6120 became a hallmark of her sound and stage presence.

For amplification, she relied on Fender Pro Reverb amps for live performances, favoring smaller amps in the studio: “Those Fenders are roadworthy, but they’re too loud to record with. I play through small amps in the studio because the size doesn’t matter, just the overdrive and tone. For recording, I mainly play through a tiny Valco amp with one 10″ speaker. It just sounds great and it’s got a great reverb in it.” Her pedalboard was equally essential to her signature sound, including a Fulltone tremolo, Univox Super Fuzz, and a Maxon delay, alongside the Fender amps’ built-in reverb and tremolo. This carefully curated gear setup was instrumental in crafting the Cramps’ otherworldly guitar tones.

The Cramps, with Poison Ivy at its core, were a band that discovered their formula and adhered to it relentlessly. They saw no need for reinvention when they had achieved their unique perfection. Their distinctive “phantasmic punkabilly” sound (a more accurate descriptor than “psychobilly,” which often describes bands inspired by The Cramps) fueled eight studio albums of consistently high quality and countless worldwide tours. Their final performance on November 4, 2006, in Tempe, Arizona, marked a quiet end to a revolutionary career. Lux Interior’s unexpected passing in 2009 marked the definitive end of The Cramps and the public persona of Poison Ivy Rorschach.

Since Lux’s death, Kristy Wallace has retreated from the public eye, allowing Poison Ivy to rest alongside her partner. This withdrawal is understandable; she gave everything to rock and roll as Poison Ivy. Her contribution is immense: she was a true revolutionary, a sonic architect who masterfully combined horror movie soundtracks, 50s rock and roll, and burlesque aesthetics. The Cramps were the antithesis of mainstream music, a defiant middle finger to polish and predictability. Poison Ivy redefined rock and roll guitar, leaving an indelible mark on music history. Let us celebrate her as the icon she is, the phantom force behind one of punk rock’s most important and influential bands. Hail Poison Ivy! God save the queen of rock ‘n’ roll guitar!

Note: The original article also included sections on Duane Eddy’s passing and a promotional closing, which are not directly relevant to the focus on “poison ivy cramps guitar” and have been omitted to maintain thematic consistency and focus.