If you’re looking to truly understand your guitar and gain freedom across the fretboard, learning the chromatic scale is an invaluable step. While you might not frequently play the chromatic scale directly in your music, its primary value is theoretical, offering a foundational understanding that translates to practical guitar skills.

Navigating the guitar fretboard can be challenging. Many guitarists find the sheer number of frets and notes overwhelming, leading to frustration and a feeling of being confined to specific areas of the neck. This can result in repetitive playing, sticking to familiar patterns and licks, and hindering your overall progress.

If this resonates with you, the chromatic scale is your key to unlocking the fretboard. Mastering it will empower you to:

- Play confidently in all 12 musical keys: Eliminate the fear of wrong notes and playing out of key.

- Improvise and solo freely across the entire neck: Move beyond limited positions and explore new sonic territories.

- Discover diverse chord voicings: Play chords in different areas of the fretboard for varied textures and sounds.

- Create original solos and patterns: Break free from relying on the same old licks and develop your unique voice.

If you’re feeling stuck or limited in your playing, understanding the chromatic scale is a crucial step towards advancing your skills. It also builds a strong foundation in music theory as applied to the guitar, setting you up for further musical exploration.

So, let’s dive in! Here’s everything you need to know about the chromatic scale and why it’s so important for guitarists:

Understanding the Musical Alphabet for Guitarists

Before exploring the chromatic scale, it’s essential to grasp the concept of the musical alphabet. Western music uses letters to represent notes, but unlike the standard alphabet, the musical alphabet only has seven letters:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|

“G” marks the end of the musical alphabet. After G, it cycles back to A. This means you won’t find notes labeled H, I, or J in music. Similarly, on your guitar, you’ll encounter A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, but not H, I, or J.

However, Western music actually utilizes 12 notes, not just seven. The letters A through G only account for seven of these. So, where do the other five come from?

Sharps and Flats: Expanding the Musical Alphabet

The remaining five notes are created using sharps and flats. A sharp symbol (#) raises a note’s pitch, while a flat symbol (b) lowers it.

Sharps and flats represent notes that exist between most of the notes in the musical alphabet. While the letters appear sequentially in the alphabet, musically, they are often separated by a “tone” or “whole step.” For example, there’s a whole step between A and B, and between C and D.

These whole steps are composed of two smaller intervals called “semitones” or “half-steps.” Most musical alphabet letters are separated by two semitones, meaning there’s a note in between. What are these in-between notes?

These are notes that are one semitone higher than the first note and one semitone lower than the second. Between A and B, for example, lies the note A sharp (A#) or B flat (Bb).

This single note has two names. The same principle applies to other notes in the musical alphabet. Between C and D, you’ll find C sharp (C#) or D flat (Db).

Understanding this might seem complex initially. However, a simple analogy can help clarify it. Imagine A as the number 1 and B as the number 2.

A# or Bb is the note exactly halfway between them, like 1.5.

Adding 0.5 to 1 (A) gives you 1.5 (A#). Subtracting 0.5 from 2 (B) also results in 1.5 (Bb).

The endpoint is identical; only the approach differs. Similarly, A# and Bb are the same pitch, sounding exactly alike, just named differently. The same applies to all sharps and flats between musical alphabet notes.

In a musical context, especially within a specific key, the naming convention—whether to use a sharp or flat—becomes more relevant. However, for now, remember that A# and Bb (and similar pairs) represent the same pitch.

What is the Chromatic Scale?

When we incorporate all the sharps and flats between the notes of the musical alphabet, we arrive at 12 unique notes. These 12 notes constitute the chromatic scale, encompassing all the notes used in Western music. The chromatic scale in order is:

| A | A#/Bb | B | C | C#/Db | D | D#/Eb | E | F | F#/Gb | G | G#/Ab |

|---|

Several key points are crucial to remember:

Firstly, not every letter in the musical alphabet has a sharp or flat counterpart.

Specifically, there is no B# or E#. Consequently, there’s also no Cb or Fb. B# is essentially C, and Fb is essentially E. The 12 notes listed above are the only notes in Western music.

Each interval between consecutive notes in the chromatic scale is a semitone. The interval from A to A# is a semitone, and from A# to B is another semitone. Therefore, from A to B, there are two semitones, or a whole tone. However, between B and C, and between E and F, there is only a semitone, because there is no B# or E#.

This is vital to remember. Many beginners find it tricky to recall which notes lack sharps and flats. A helpful mnemonic is to remember the phrase “Let it BE,” like the famous Beatles song. This reminds you that B and E do not have sharps (in standard chromatic scales).

The Chromatic Scale on Your Guitar Fretboard

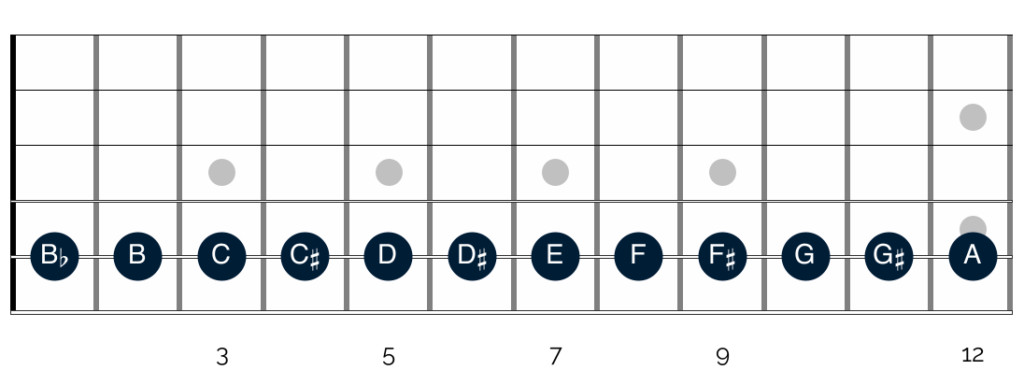

Understanding the chromatic scale becomes much clearer when you visualize it on your guitar fretboard. The chromatic scale is simply playing all 12 notes in order. Here’s how it looks starting on the note A, played on the open A string:

Chromatic scale starting on the A string of a guitar

Chromatic scale starting on the A string of a guitar

Analyzing the chromatic scale on the fretboard reveals two fundamental principles about guitar fretboard structure:

- Each fret equals one semitone: Moving one fret up or down changes the pitch by one semitone. Two frets equal a whole tone.

- 12 frets cover the chromatic scale: By the 12th fret, you’ve played all 12 notes of the chromatic scale, meaning you’ve played every note used in Western music.

These principles apply universally across every string on your guitar. The logic remains consistent regardless of the string you are playing.

On every string, moving one fret equals one semitone, and by the 12th fret, you’ve played the complete chromatic scale.

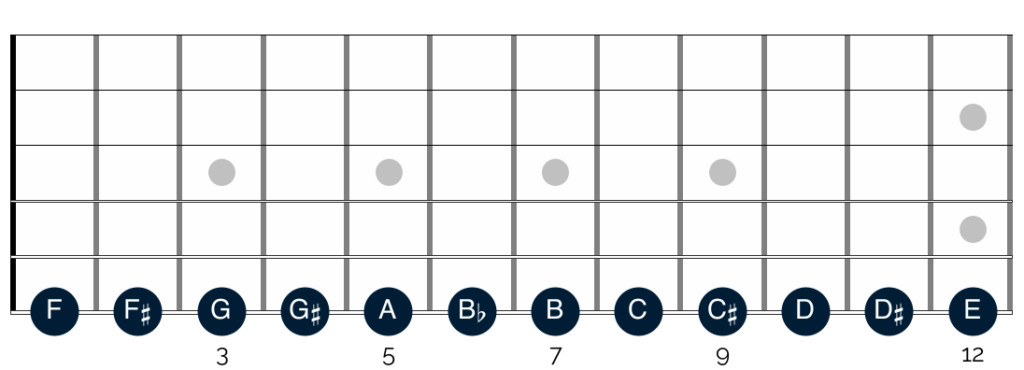

The only string-to-string difference is the starting note of the chromatic scale. Let’s see this on the low E string:

Chromatic scale starting on the low E string of a guitar

Chromatic scale starting on the low E string of a guitar

Again, you see the same consistent logic. Starting on the open E string, each fret ascends by a semitone, progressing through the chromatic scale. By the 12th fret, all 12 notes are covered.

Beyond the 12th Fret: Octaves and Repetition

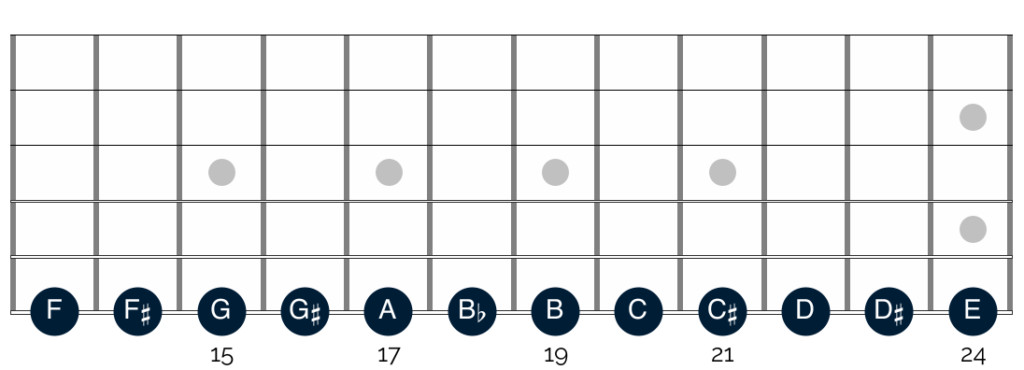

You might wonder what happens beyond the 12th fret. The note pattern is remarkably consistent and easy to grasp.

As shown in the fretboard diagrams, the 12th fret brings you back to the starting note of the chromatic scale, but an octave higher.

For example, on the low E string, the open string is E. The 12th fret is also E, but one octave higher. In the context of the chromatic scale, it’s the same note in a higher register. The notes following the 12th fret mirror the notes before it.

Here’s the chromatic scale on the low E string extending beyond the 12th fret:

Chromatic scale on the E string of a guitar, showing two octaves

Chromatic scale on the E string of a guitar, showing two octaves

The notes repeat after the 12th fret. The diagram illustrates a 24-fret guitar, capable of playing two octaves of the chromatic scale on each string.

Even with guitars having 21 or 22 frets, you can view the fretboard as repeating its note pattern. This is why most guitars have fret markers at the 12th fret – often two inlays – to visually indicate this octave point.

Why Learn the Chromatic Scale for Guitar?

So far, we’ve defined the chromatic scale and its construction. However, as you might have noticed, the chromatic scale doesn’t naturally form practical shapes on the fretboard. You won’t typically play it directly in a musical performance.

This raises the question: how do you actually use the chromatic scale, and what are its benefits?

Essentially, the chromatic scale provides a framework for understanding all the notes on your guitar. It reveals the fundamental structure of the fretboard and the relationship between frets, semitones, and whole tones.

This understanding is beneficial in several ways:

Playing in All Keys: Transposition Made Easy

Knowing the location of notes across your guitar neck makes playing in different keys significantly easier. If you typically improvise in A, with chromatic scale knowledge, you can transpose your A licks and phrases to B, C, D, or any other key.

Let’s illustrate this further:

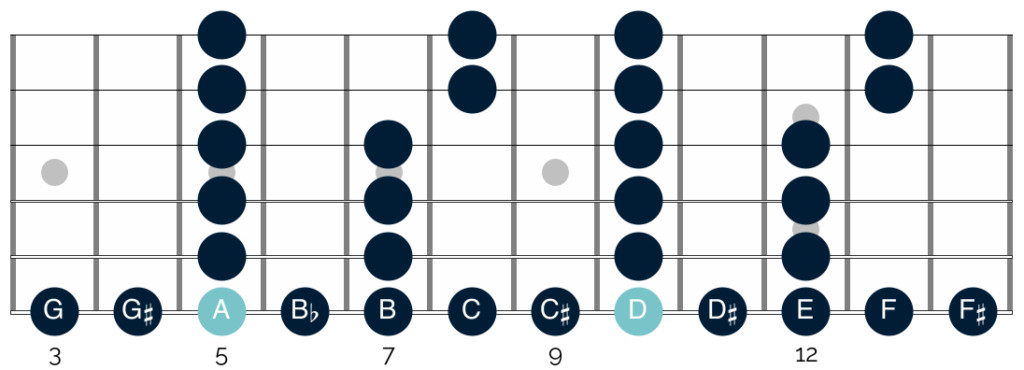

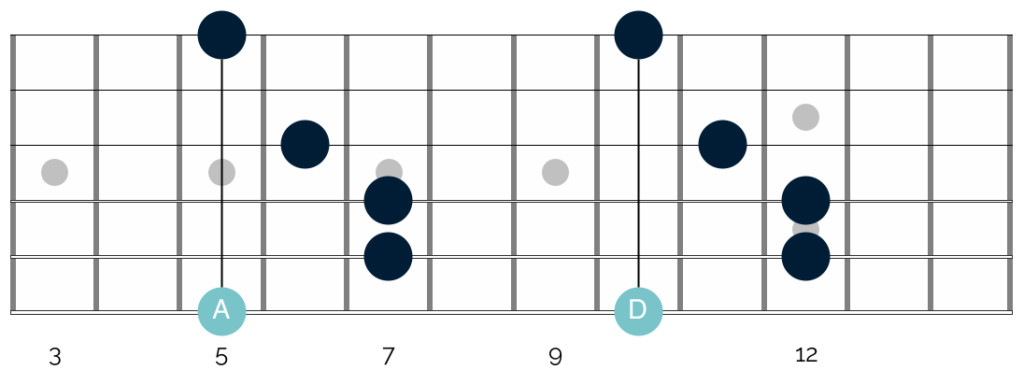

Chromatic scale and pentatonic scales for transposition on guitar

Chromatic scale and pentatonic scales for transposition on guitar

This diagram shows the chromatic scale notes on the low E string, along with the shapes of the A minor pentatonic and D minor pentatonic scales. Notice that the scale shapes are identical; only their fretboard positions differ.

If you’re comfortable playing in one key, understanding the chromatic scale allows you to effortlessly shift your “go-to” licks and phrases to any other key.

To play in C, for example, find the C note on your 6th string. Start your minor pentatonic scale shape from that C, and you’re now playing in C minor pentatonic. You can then locate the remaining scale shapes relative to this starting point, enabling you to play your familiar licks in any key.

Mastering Barre Chords Across the Fretboard

The same principle applies to moving barre chords around the neck. Again, visualizing this on the fretboard helps:

Chromatic scale and barre chord shapes on guitar

Chromatic scale and barre chord shapes on guitar

Barre chords aren’t usually presented this way, so this might initially look confusing. However, it simply shows an A major barre chord shape and a D major barre chord shape.

Like the pentatonic scale example, the chord shapes are identical. The only difference is their position on the fretboard.

If you know an A major barre chord, combining that with chromatic scale knowledge instantly unlocks B major, C major, D# major, and any other major barre chord.

Understanding the chromatic scale empowers you to play diverse lead lines and chords all over your guitar neck.

Focus on the Low E and A Strings for Practical Use

For practical application, you don’t need to memorize the chromatic scale notes on all six strings immediately. Focusing on the low E and A strings is a highly effective starting point. Here’s why:

Firstly, most scales and barre chords root notes are located on the low E and A strings. Knowing these notes allows you to easily transpose scale and chord shapes across the fretboard.

Secondly, as explained in more detail in this article octave shapes, you can use octave shapes starting from the low E and A strings to quickly find the same notes on other strings.

This connects notes on your lower strings to the rest of the fretboard without needing to memorize every single note location individually.

If you want to practically use the chromatic scale but feel overwhelmed by learning it across all strings, don’t worry! Mastering the chromatic scale notes on just the low E and A strings provides a rapid and effective way to start applying it to your playing.

Closing Thoughts

So, there you have it – an overview of the chromatic scale and its practical applications for guitarists.

As with many theoretical aspects of guitar playing, this is not an exhaustive exploration. Understanding the chromatic scale also significantly aids in grasping intervals and scale construction.

However, those are in-depth topics requiring separate discussions. They will be covered in future articles.

In the meantime, I hope this explanation helps you begin working with the chromatic scale. From a theoretical perspective, it’s fundamental to understanding music theory on the guitar. Practically, it reveals the logical structure of your fretboard, benefiting both your lead and rhythm playing and making you a more versatile and knowledgeable musician.

Good luck! Let me know how you progress, and feel free to reach out with any questions. Leave a comment or email me at [email protected]. I’m always happy to help!