Jerry Reed’s song “Guitar Man” tells a quintessential Nashville story: a musician chasing a dream. The lyrics paint a vivid picture of determination and the sometimes harsh realities of the music industry:

‘Well, I quit my job down at the car wash/ left my mama a goodbye note/ by sundown I’d left Kingston/with my guitar under my coat/ I hitchhiked all the way down to Memphis/ got a room at the YMCA/ for the next three weeks I went huntin’ them nights/just lookin for a place to play/ well, I thought my pickin would set em on fire/ but nobody wanted to hire a guitar man.’ – Guitar Man – Jerry Reed

While the ’68 Comeback Special often receives accolades as Elvis Presley’s artistic resurgence, the groundwork for this triumph was laid earlier. A crucial, yet sometimes overlooked, chapter in Elvis’s journey back to creative prominence is the “Guitar Man” sessions of September 1967. These sessions, arriving after the gospel triumph of the “How Great Thou Art” album, were intended to be Elvis’s full-fledged return to contemporary music and inadvertently spotlighted the indispensable contribution of guitar virtuoso Jerry Reed.

The Genesis of the Guitar Man Sessions: More Than Just a Comeback

To understand the significance of the “Guitar Man” sessions, it’s important to consider the context. Elvis’s preceding album, “How Great Thou Art,” released in May 1967, was a deeply personal project where he exerted considerable creative control. This gospel album was a critical and commercial success, showcasing Elvis’s vocal power and his commitment to music that resonated with his soul. However, the need for a hit single in the secular market remained.

The “Guitar Man” sessions, initially planned for Hollywood in August 1967, were intended to capitalize on this momentum. Elvis had personally requested a diverse set of songs for consideration, revealing his evolving musical tastes and desire to experiment. The planned tracklist included a mix of country, pop, and R&B influences, hinting at a stylistic shift: We Call On Him, He Comes Tomorrow, Ramblin’ Rose, From A Jack To A King, After Loving You, Brown Eyed Handsome Man, Baby What You Want Me To Do, The Wonder Of You, Pledging My Love, The Fool, After Loving You, and crucially, Guitar Man. The latter, Jerry Reed’s self-penned tune, had caught Elvis’s ear on the radio, sparking his determination to record it.

However, fate intervened. An incident involving Richard Davis, who accidentally killed a gardener while driving one of Elvis’s cars in Los Angeles, prompted Colonel Parker to abruptly relocate the entire operation. Fearing legal repercussions, Parker swiftly moved Elvis and his entourage to Las Vegas, effectively cancelling the Hollywood session.

Relocating to Memphis after the Las Vegas detour made Nashville the logical choice for rescheduling. The sessions were reset for September 10th and 11th, 1967, with Felton Jarvis firmly at the helm. Any initial plans involving Billy Strange were abandoned, giving Jarvis complete creative control. Having witnessed the success of “How Great Thou Art,” Jarvis recognized the need for a “real big hit single” – something that had eluded him with “Love Letters.”

Jerry Reed Enters the Studio: The Missing Ingredient

The sessions commenced with “Guitar Man,” but it quickly became apparent that something was missing. The studio musicians, despite their proficiency, couldn’t replicate the distinctive sound and feel of Jerry Reed’s original recording. The unique guitar work, integral to the song’s identity, proved elusive.

As the story goes, someone suggested Jerry Reed might be fishing. After a search, Chet Atkins’ assistant, Mary Lynch, managed to reach him by phone. Reed, in his characteristic laid-back style, agreed to come to the studio. Felton Jarvis vividly described Reed’s arrival: “like a sure-enough Alabama wild man. You know, he hadn’t shaved in about a week, and he had them old clogs on – that was just the way he dressed.” Elvis’s humorous reaction, “Lord, have mercy, what is that!”, broke the ice.

Despite the initial culture clash – Reed’s rustic appearance contrasting with Elvis’s and Jarvis’s more polished looks – musical respect prevailed. Jerry Reed, though only 30 years old, was already a seasoned musician. A fellow Atlanta native and alumnus of the Bill Lowery School of Music (like Jarvis), Reed had been writing and recording for a decade. Chet Atkins, recognizing his talent, had brought him into session work after Reed moved to Nashville in 1962. While Reed had yet to achieve major recording success, “Guitar Man” had marked his first foray onto the country charts earlier that year, reaching number 53. Ironically, the song that Elvis wanted to capture was Reed’s own breakthrough hit.

Reed immediately diagnosed the issue. The Nashville session musicians were using standard guitar picks, while his signature sound relied on fingerpicking and a unique guitar tuning. He explained, “these guitar players in here are playing with straight picks, and, you know, Reed plays with his fingers.” He then grabbed his electric gut-string guitar, tuned the B-string up a whole tone and the low E-string down a whole tone, creating his distinctive open tuning. As soon as he played the intro, Elvis, as Reed recalled, had his “eyes light up” – they had found their “Guitar Man” sound.

Jerry Reed and Elvis Presley collaborating in Nashville, 1967, during the Guitar Man sessions

Jerry Reed and Elvis Presley collaborating in Nashville, 1967, during the Guitar Man sessions

The Magic of Collaboration: “Guitar Man” and “Big Boss Man” Take Shape

With Jerry Reed present, the atmosphere in RCA Studio B transformed. He didn’t just play; he took charge, becoming an active collaborator. As Ernst Jorgensen describes in “A Life In Music,” Reed was “coaching the musicians, encouraging them, egging them on.” Felton Jarvis, in turn, seemed content to oversee this creative burst.

The music took on a vibrant, shimmering quality, distinct from Elvis’s previous recordings yet retaining the driving rhythm that defined his signature style. Elvis himself was fully engaged, dispensing with any self-deprecation or joking, focusing entirely on the music.

The studio tapes reveal the dynamic interplay. On the first take of “Guitar Man,” Reed, initially flustered, exclaimed, “Phew, I haven’t played all weekend!” Amidst lighthearted banter, they refined the tempo and intro. Reed, working alongside Jarvis, suggested a fade-out ending. Jarvis spurred Elvis on, urging him to “Sing the living stuff out of it, El!”

As they progressed through takes, Elvis began improvising, incorporating a playful nod to Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” into the outro. By the tenth take, it had evolved into a full-blown, infectious quote that had everyone laughing. Reed was ecstatic, describing it as “just a jamming session” where he felt pumped up, feeding off Elvis’s energy in a “snowball effect.” He recognized it as one of those “rare moments in your life you never forget.” By the twelfth take, they had a raw, energetic country record. Reed added a second guitar part, and the session rolled on.

Riding this creative wave, they transitioned seamlessly to Jimmy Reed’s blues classic, “Big Boss Man.” Jerry Reed remained at the forefront, his “Alabama wild man” persona injecting every note with exuberance and musicality. Charlie McCoy’s harmonica and Boots Randolph’s saxophone amplified the bluesy undertones. Elvis, channeling a raw, blues-infused vocal style, impressed Jarvis, who encouraged him to sound “like you’re mad, like you’re mean.” The atmosphere was relaxed and fun, with Jarvis exclaiming, “That’s a gas, man. Go apeshit!” They nailed “Big Boss Man” in eleven takes, the studio buzzing with energy.

By midnight, they had two standout tracks in the can. The sound was fresh and innovative, a unique blend of acoustic, guitar-driven crispness with an R&B funkiness that defied Nashville conventions. The engineering captured the seemingly chaotic jamming with remarkable precision.

Publishing Disputes and Lingering Frustration

Despite the musical triumphs, the sessions weren’t without their challenges. As Jerry Reed prepared to leave after “Big Boss Man,” Freddie Bienstock’s request for standard publishing arrangements hit a snag. Lamar Fike, tasked with the negotiation, found Reed unwilling to relinquish any of his writer’s share. With “Guitar Man” already recorded and sounding phenomenal, Reed had no incentive to compromise.

Elvis’s refusal to intervene left Bienstock in an awkward position, his earlier oversight in clearing the publishing with Reed for the initially planned Billy Strange session exposed. Reed, feeling undervalued and pressured, stood his ground. He famously retorted, “Why didn’t you tell me this before I come here? I could have saved you all a lot of effort… You done wasted Elvis’ time. You done wasted all these musicians’ time, and RCA’s time: I’m not going to give you my soul.” Even the veiled threat that the record might not be released unless an agreement was reached didn’t sway Reed. “Mr. Bienstock, I’ll put it to you this way. You don’t need the money, and Elvis don’t need the money, and I’m making more money than I can spend right now – so why don’t we just forget we ever recorded this damn song?”

Scotty Moore, witnessing the standoff, admired Reed’s resolve: “They got Jerry off in a corner, but he wouldn’t sell.” Reed’s leverage was clear: the song was recorded, Elvis loved it, and its magic was undeniable. (Ironically, a similar publishing conflict would resurface during the “Suspicious Minds” sessions at American Sound Studios in 1969.)

The musicians were taken aback by this blatant intrusion of business into an Elvis Presley session. While aware of the industry’s often arbitrary rules, they had never witnessed such a direct challenge. Reed left the session, and while it continued into the early hours, the creative spark had dimmed.

The Session Continues: “You’ll Never Walk Alone” and “Hi-Heel Sneakers”

The following night, the sessions resumed, but the energy had shifted. They grappled to find suitable material, settling for less inspiring songs. Elvis, ever the professional, remained committed, striving to inject enthusiasm even into uninspired material.

He took to the piano for “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” a Rodgers and Hammerstein ballad he admired since Roy Hamilton’s R&B rendition. Elvis delivered a powerful, heartfelt performance, channeling the fervor of Hamilton and gospel singer Jake Hess. While his piano skills were rudimentary, his engagement at the keyboard always indicated a deeper connection to the music.

A brief moment of revival occurred when guitarists Chip Young and Harold Bradley spontaneously played the intro to “Hi-Heel Sneakers,” a 1964 Tommy Tucker hit with a similar bluesy vibe to “Big Boss Man.” Elvis eagerly joined in, and they cut a strong version. However, Felton Jarvis later cautioned Harold Bradley against “pitching songs” directly, citing Freddie Bienstock’s disapproval of unscheduled song selections.

“U.S. Male” and the End of an Era (For Nashville, For a While)

Jerry Reed returned for another Elvis session in January 1968. According to Jerry Schilling, Elvis grew frustrated by the lack of suitable material. It was Chip Young who suggested Jerry Reed play “U.S. Male,” his talking blues song. In a 2005 interview, Reed credited steel guitarist Pete Drake for prompting him to pitch another song. “Pete and I knew each other in Atlanta… He said, ‘Have you got anything else?’ I said, ‘No, man. Listen, this is enough for me, believe me.’ Then Elvis said, ‘Yeah, have you got any other songs?’ I said, ‘Well … uh … yeah’.” After Reed played “U.S. Male,” Elvis immediately wanted to record it.

Despite Freddie Bienstock’s continued unease about hallway song pitches, the need for a new single outweighed protocol. However, “U.S. Male” proved challenging, falling apart after the first take, possibly due to its lyrical complexity and intricate guitar work. They pivoted to “The Prisoner’s Song,” but Elvis’s playful lyric alterations rendered it unusable. They eventually circled back to “U.S. Male,” imbuing it with a country feel and Jerry Reed’s signature guitar licks.

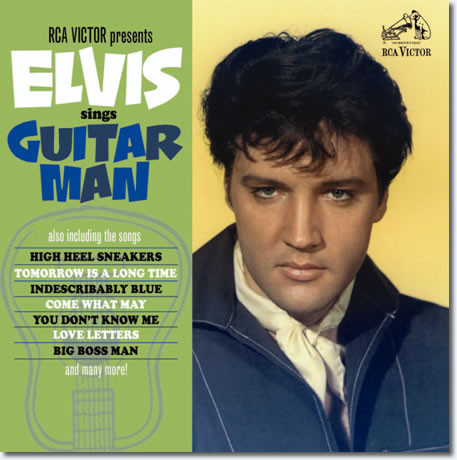

These two nights in September 1967 and January 1968 yielded only four songs. Unbeknownst to them at the time, it would be the last Nashville session with this particular band and Elvis’s final Nashville recording for thirty months. However, in 2011, the “classic” album that arguably should have been released in 1967 finally materialized with the FTD special edition release, “Elvis Sings Guitar Man.”

September 10, 1967, RCA Studio B – Nashville, Tennessee

September 11, 1967, RCA Studio B – Nashville, Tennessee

- Mine

- Singing Tree

- Just Call Me Lonesome

- Hi Heel Sneakers

- You Don’t Know Me (Remake)

- We Call On Him

- You’ll Never Walk Alone

September 12, 1967, RCA Studio B – Nashville, Tennessee

- Singing Tree (Remake)

- Singing Tree (Harmony Vocal Overdub)

Much of this account draws from Ernst Jorgensen’s “A Life In Music – The Complete Recording Sessions” and Peter Guralnick’s “Careless Love.” For those wanting to explore Jerry Reed’s solo work, the CD “Jerry Reed” offers an excellent introduction to this remarkable artist, featuring his own versions of “Guitar Man” and “U.S. Male,” alongside hits like “Tupelo Mississippi Flash,” “Amos Moses,” and “East Bound And Down.”

Rediscovering the Guitar Man Sessions: A Legacy of Innovation

The “Guitar Man” sessions, while not immediately resulting in a dedicated album release in 1967, stand as a pivotal moment in Elvis Presley’s musical evolution. They showcased his willingness to embrace new sounds and collaborate with artists like Jerry Reed who pushed his creative boundaries. These sessions yielded iconic tracks that remain fan favorites and highlight the crucial role of Jerry Reed in shaping Elvis’s sound during this period. The FTD “Elvis Sings Guitar Man” collection finally allows listeners to fully appreciate the depth and innovation of these landmark recordings.