Have you ever come across those ads promising to teach you guitar in minutes? It sounds too good to be true, right? While you can indeed learn something quickly, truly understanding and applying that knowledge is what makes you a guitar player. Simply mimicking isn’t learning. To really progress, understanding the “why” behind the “how” is crucial from the start.

This lesson, the first in our “Easy Songs for Beginners” series, aims to do just that. We’ll learn to play a song and understand the musical elements within it, allowing you to truly play and apply these skills to other songs. We’ll start with the basics, then spice things up with strumming variations, a simple bass line, and even explore rhythm riffs and leads in a follow-up lesson, “Adding Some Personal Touches.” Learning guitar should be enjoyable and rewarding, not just a quick trick!

The Bare Essentials

Ever seen those over-the-top guitar ads? They make it seem like anyone can become a guitar god overnight. To move forward here, I’m assuming you’ve at least held a guitar and understand some basic guitar terms. If not, begin with our “Absolute Beginners Chords lesson.” Just learn the E minor chord – the first one taught – and you’ll be ready. Seriously!

The song for this lesson is Horse With No Name, by America, written by Dewey Bunnell. The entire song uses just two chords. You already know one: E minor. The second one is a bit more complex to name, but easy to play:

The Em chord is famously simple. But how did Bunnell come up with the second chord? It was likely a happy accident or just experimentation on the fretboard. He probably thought, “Hey, that sounds pretty cool!”

Both chords are easy to finger. Em uses the second fret of the D and A strings. For the second chord, often called Dadd6add9, simply shift those fingers to the G and low E strings. It’s a small adjustment, requiring minimal thought. Use the finger on the A string’s second fret (likely your index or middle finger) for the low E string’s second fret. Similarly, move the finger from the D string to the G string. It’s like finger gymnastics!

(We’ll discuss the “Dadd6add9” name later. If you’re curious now, jump to “What is that chord really?”)

The song’s rhythm is in 4/4 time – four beats per measure. The chords change every measure. Start with a simple downstroke on each of the four beats, or on beats one, two, and four for a slight variation. Remember, the song has a moderate tempo – not fast, not slow. When learning, go as slow as needed to smoothly change chords while keeping a steady beat. A metronome is very helpful here.

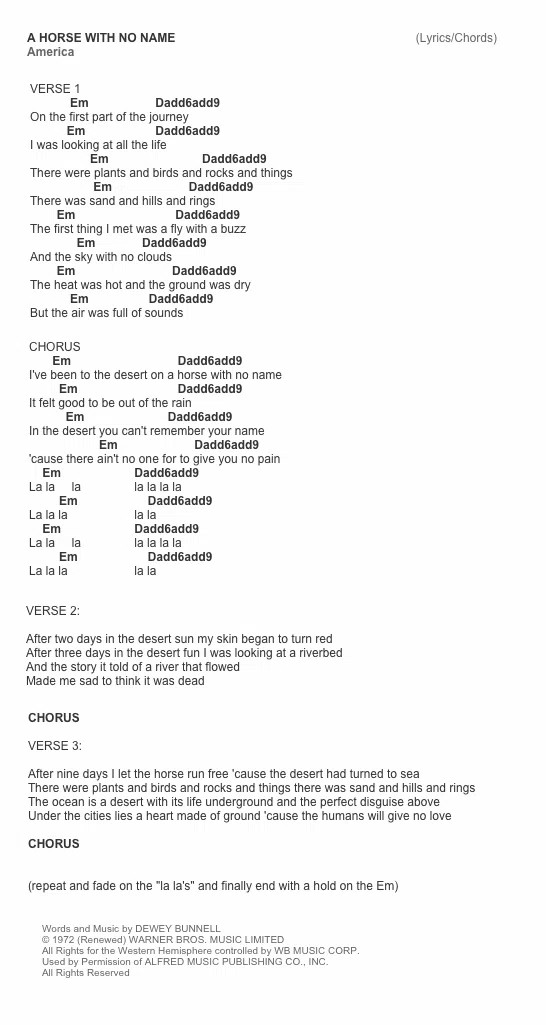

Here’s a simple chart showing the verse and chorus chord progression:

Horse With No Name by America cheat sheet chords and lyrics

Horse With No Name by America cheat sheet chords and lyrics

Straightforward, isn’t it? Let’s move to the next step.

Getting Creative

Beginners usually focus on chord recognition and finger placement. You need to know the chord names and how to form them. Then comes smooth transitions between chords. With “Horse With No Name”, these are minimal concerns, allowing you to concentrate on strumming.

You might think I overemphasize rhythm, but it’s incredibly important. It’s not just about keeping time, but creating patterns that enhance the song, making it more enjoyable to play and listen to.

“It’s just hitting strings,” you might think. How hard can it be?

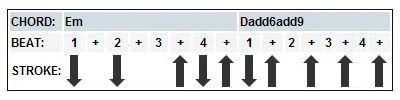

Not hard at all, if you’re conscious of it from the beginning. Here’s the basic rhythm pattern I suggested earlier:

An symbol means an upstroke (towards your head), and is a downstroke (towards the floor).

This works, but it’s quite basic, mainly useful for timing practice. To get closer to the original song’s feel, we need to work on upstrokes and the “in-between” beats. We’ll use eighth notes for this – dividing each beat in half. Instead of counting “1, 2, 3, 4,” we count “1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and…” The tempo (beats per minute) remains the same, though it might feel faster initially. Don’t worry, it’s easy to grasp.

Here’s a more interesting strumming pattern, closer to the original song:

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming pattern alternateDownload MP3

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming pattern alternateDownload MP3

Again, start slowly if this is new. Slow enough to count each beat and place each stroke correctly. You’ll be surprised how quickly you pick up upstrokes, even if you’ve never tried them.

Adding Depth

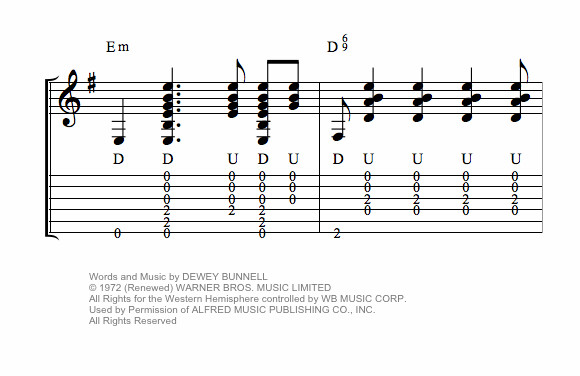

Once comfortable with strumming, let’s add a bass line. It won’t be a complex bass part, but it significantly enriches your playing with a simple technique, adding texture and depth.

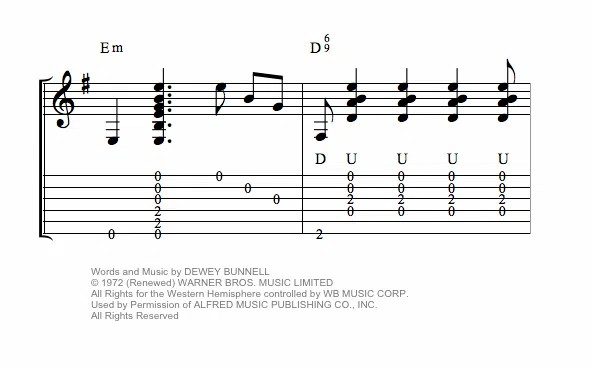

Here’s the approach: on the first beat of each measure, strike only the sixth string (the lowest note for both chords). Just that string, nothing else. Combine this with your strumming (up and downstrokes) for something like this: Downstrokes are marked “D,” upstrokes “U” for clarity:

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example oneDownload MP3

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example oneDownload MP3

Using this as a base, you can really have fun. I like to play an upstroke on the second beat of the E minor, near the bridge (away from the neck), letting it ring through the rest of the measure:

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example twoDownload MP3

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example twoDownload MP3

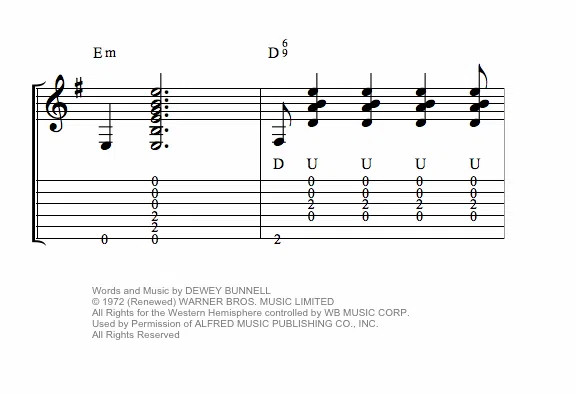

You can also pick individual strings instead of strumming. In this example, the top three strings are picked as upstrokes in the last beat and a half of the measure:

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example threeDownload MP3

Horse With No Name by America chords strumming example threeDownload MP3

Once you have a few patterns you like and can play automatically, start mixing and matching! Combine “E minor pattern 1” with “Dadd6add9 pattern 4,” and experiment. It becomes fun and challenging to discover new combinations.

Even simple songs offer many creative possibilities if you invest time and effort. Or, you can just learn the basic chords and move on. The choice is always yours.

Decoding the Chord Name

Let’s examine that second chord. Analyzing the notes on each string reveals:

As we discussed in “Building Additions and Suspensions,” this chord can have many names. Bm7 (add 4)? D6 (add 9)? E9 (sus4)? All are valid, considering the notes.

Chord context in a progression is vital for naming. Voicing, meaning note selection and placement on the guitar, is also crucial. Let’s revisit our two chords:

First, let’s determine the key. The easy way: “It starts and ends with E minor, so it’s in E minor!” That works. But listen to the chords. Em feels like “home,” a resting point. The Dadd6add9 feels unsettled, like it needs to resolve. Play them in reverse – Dadd6add9 still feels unresolved, craving resolution.

Playing the song, the F# in the bass sounds right. It fits better than D, E, or A as the root. This suggests F# as the root. Building a stack of thirds from F# and matching the chord notes (using “-” for missing notes) gives us:

The fifth (C#) and ninth (G#) are absent. We have a second A instead. So, we could call it F#m13 for simplicity, or F#m7 (no 5)(add 4)(add 6) for detail. Simpler is often better for writing. Chord naming can be debated endlessly.

What if a chord has seven notes, but you can only play six on guitar? Which note do you omit?

Traditionally, the fifth is dropped. But sometimes, even the root is omitted! (We’ll explore such chords in future lessons.) The deciding factor is often fingerability on the fretboard. For example, open strumming (no fretting) in standard tuning creates an A11 chord: E (fifth), A (root), D (eleventh), G (seventh), B (ninth), E (fifth). The third (C#) is missing, but it sounds fine. For 9th, 11th, and 13th chords, including the seventh and root is generally recommended for clarity.

Is all this naming important? It depends on your goals. Next week, we’ll see how naming the Dadd6add9 as such helps determine the modal centers of our harmonies, guiding our fills and leads. It’s less complicated than it sounds!

Please send questions, comments, or future topic suggestions via the Guitar Forums or email me at [email protected].

Until next week,

Peace

Liner Notes

“A Horse With No Name” by America is a folk-rock classic by Dewey Bunnell, reminiscent of Neil Young’s acoustic style. Ironically, in 1972, it replaced Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” as America’s number one single.