If you’ve been enjoying guitar by playing familiar songs with open chords like G, C, D, E, and A, perhaps venturing into minor or seventh chords, you’re ready to expand your musical horizons. Enter barre chords – your key to unlocking the entire fretboard. Unlike open chords that incorporate open strings, barre chords involve using your index finger to press down multiple strings at once, creating a movable chord shape.

While initially, barre chords might seem trickier to play cleanly compared to open chords, the rewards are immense. Mastering barre chords means you can play the same chord shape in 12 different positions up and down the guitar neck, effortlessly accessing a wide range of chords, including those often seen in songbooks like Bm, Ab7, or F#. This lesson will guide you through essential barre chord shapes and demonstrate their power with the classic swing tune “After You’ve Gone.”

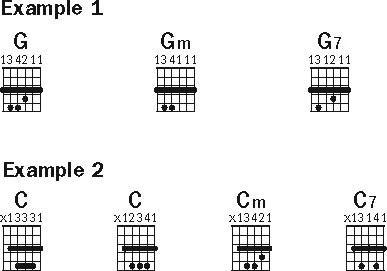

Understanding Basic Barre Chord Shapes

Let’s start with a G major barre chord, as illustrated in Example 1. Your index finger acts as a “barre,” pressing down all six strings at the third fret. Your middle, ring, and pinky fingers then form a familiar E major shape above it – middle finger on the 4th fret of the 3rd string, pinky on the 5th fret of the 4th string, and ring finger on the 5th fret of the 5th string. To understand the origin of this shape, visualize playing an open E major chord. Now, imagine placing a capo at the third fret and playing that same E chord shape above the capo. Remove the imaginary capo, and play the G barre chord – the connection becomes clear. The G barre chord is essentially an E shape chord moved up three frets, with your index finger acting as the capo.

The same principle applies to other variations. By slightly modifying the G major barre chord shape, you can create G minor and G7 barre chords. If you lift your middle finger from the G major barre chord, you get a Gm barre chord. This mirrors the relationship between open E minor and E major. Similarly, starting from the G major again and removing your pinky finger yields a G7 chord, comparable to an open E7 chord shape moved up three frets.

These G, Gm, and G7 barre chords are all rooted on the sixth string. The root note is the fundamental note of a chord, defining its name. In these G chords, the lowest note is G, located at the third fret of the 6th string. The beauty of barre chords lies in their mobility. Shifting any of these three shapes up or down the neck creates a new chord. The chord’s name changes based on the root note you are playing on the 6th string, but its quality (major, minor, or seventh) remains consistent. For instance, moving a G7 barre chord up two frets results in an A7 chord, still a seventh chord, but now with A as the root note (fifth fret, 6th string). Sliding a Gm barre chord up to the eighth fret produces a Cm chord, as the note at the eighth fret of the 6th string is C. Conversely, moving a G major chord down one fret gives you an F#/Gb major chord because the second fret of the 6th string is F#/Gb.

Exploring Fifth-String Root Barre Chords

There’s another essential family of barre chords where the root is on the fifth string. For these, you only need to barre across the top five strings, as demonstrated at the third fret in Example 2. Think of open A, Am, and A7 chords with a capo at the third fret to grasp the connection to these barre chord shapes. To play a C major barre chord, barre strings 5–1 with your index finger at the third fret. Then, use your ring finger to barre across strings 4–2 at the fifth fret. If this feels challenging, you can simplify it by omitting the highest note on the 1st string and only barring strings 5-1 with your index finger and placing your ring finger on the fifth fret of the 4th string. Another fingering option is to use your middle, ring, and pinky fingers on strings 4, 3, and 2 respectively at the fifth fret, instead of a ring-finger barre across those strings.

barre chord diagrams

barre chord diagrams

These C, Cm, and C7 chords are called fifth-string-root chords because their root note is on the fifth string, differentiating them from the previous set of sixth-string-root chords. As you move these fifth-string-root chords up or down the neck, the chord name changes based on the note played on the fifth string. For example, a C major chord moved up to the sixth fret becomes a D#/Eb major chord. A Cm chord shifted down to the second fret becomes a Bm chord, and a C7 chord moved to the ninth fret transforms into an F#7/Gb7 chord.

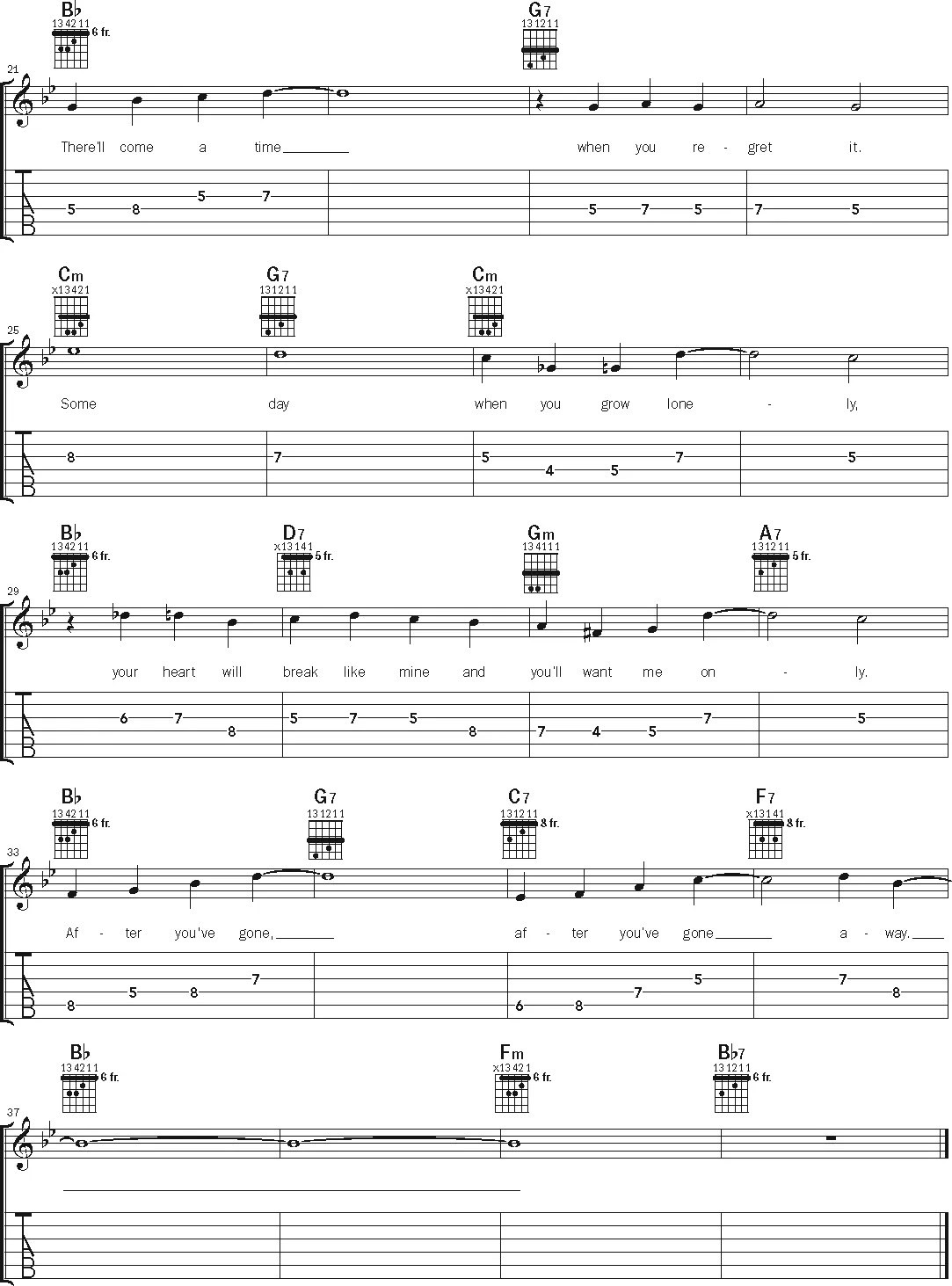

Now, let’s put these barre chords into practice with a song. The swing standard “After You’ve Gone,” composed in 1918 by Henry Creamer and Turner Layton, has been interpreted by countless artists, including jazz legends like Charlie Parker, western swing group Riders in the Sky, and famously, guitarist Django Reinhardt with the Quintet of the Hot Club of France. The arrangement provided here utilizes all six of the barre chord shapes we’ve discussed. Playing through it will demonstrate how barre chords can unlock a whole new world of musical possibilities on the guitar.

guitar notation for song

guitar notation for song

This article was originally featured in the September/October 2023 issue of Acoustic Guitar magazine.