For guitarists aiming to inject authentic blues emotion into their solos, mastering Blues Guitar Scales is an absolute game-changer. These scales are the very foundation of that distinctive “bluesy” sound, wielded by countless blues and blues rock icons to create unforgettable music. Often, after conquering the minor pentatonic scale, the blues scale becomes the next essential step for aspiring lead guitarists.

If you’re just starting your blues guitar journey and haven’t yet explored the minor pentatonic scale, I highly recommend checking out “A Beginner’s Guide To The Minor Pentatonic Scale.” It provides crucial groundwork for blues improvisation and soloing.

However, if you’re already comfortable with the minor pentatonic scale and eager to expand your lead guitar vocabulary, diving into blues scales is a fantastic move. It’s the key to adding depth and nuance to your playing.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore everything you need to know about blues guitar scales:

- Understanding the core differences between blues scales and both major and minor pentatonic scales.

- Learning how to effectively use both minor and major blues scales in your playing.

- Discovering techniques to blend major and minor blues scales, adding richness and complexity to your solos.

- Exploring iconic songs that showcase the power of blues scales.

Let’s get started and unlock the soulful world of blues guitar scales.

Diving into Scale Theory Basics

Before we jump into playing the blues scale, let’s touch upon some fundamental music theory. Don’t worry, we’ll keep it concise and focused on what you need to understand. A basic grasp of scale construction will significantly enhance your understanding of what you’re actually playing, which is crucial for musical growth.

To understand the blues scale, we first need to look at the major scale. This is the bedrock of Western music, and all other scales are often described in relation to it.

The major scale is a heptatonic scale, meaning it comprises 7 notes within an octave. Its formula is:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

These numbers represent the intervals within the scale. ‘1’ is the root note, ‘2’ the second, and so on. In the key of A major, the notes are:

A B C♯ D E F♯ G♯

So, in A major, 1=A, 2=B, 3=C♯, etc. This formula serves as the reference point for understanding other scales.

Let’s consider the minor scale. Its formula is:

1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7

The ‘b’ symbol means “flat,” indicating that the note is lowered by a half step. In A minor, this alters the major scale notes:

A B C D E F G

The 3rd, 6th, and 7th degrees are flattened, removing the sharps present in the A major scale.

Pentatonic Scale Foundation

While the major scale is fundamental, it’s not often used in its pure form in popular music. It often lacks the tension and “edge” that we crave in genres like blues and rock.

Instead, scales derived from the major and minor scales are more common, such as pentatonic scales.

A pentatonic scale contains only 5 notes per octave (penta = five).

There are two main types: major pentatonic and minor pentatonic. Both are vital in blues and rock guitar, especially the minor pentatonic, which has become synonymous with these genres.

The minor pentatonic scale is derived from the minor scale with the formula:

1 b3 4 5 b7

It uses notes from the minor scale but only five of them.

Similarly, the major pentatonic scale, from the major scale, has this formula:

1 2 3 5 6

It also uses notes from the major scale but in a five-note structure.

Unveiling the Blues Scale

At this point, you might be wondering about pentatonic scales and where the blues scale fits in.

The easiest way to understand the blues scale is to think of it as a pentatonic scale with just one added note. This makes the blues scale a hexatonic scale (hexa = six).

There’s a minor blues scale, almost identical to the minor pentatonic, just with one extra note.

And there’s a major blues scale, similarly close to the major pentatonic, also with a single added note.

This extra note is often called the “blue note.” It’s a chromatic note that enriches both pentatonic scales harmonically.

The blue note introduces sounds and feelings that are harder to achieve with just pentatonic scales.

So, if you want to inject more depth and variety into your lead guitar playing, learning both minor and major blues scales is an excellent step.

The fantastic news is that the shapes for blues scales are very similar to pentatonic scale shapes. Let’s explore this in detail for both minor and major contexts.

The Minor Blues Scale: Your Blues Foundation

The minor blues scale is likely to be your most frequently used blues scale, and for good reason, which we’ll explore shortly.

As mentioned, it’s just the minor pentatonic scale with one added note: the b5 (flat fifth), also known as the blue note. All other notes remain the same.

The minor pentatonic scale structure is:

1 b3 4 5 b7

And the minor blues scale structure is:

1 b3 4 b5 5 b7

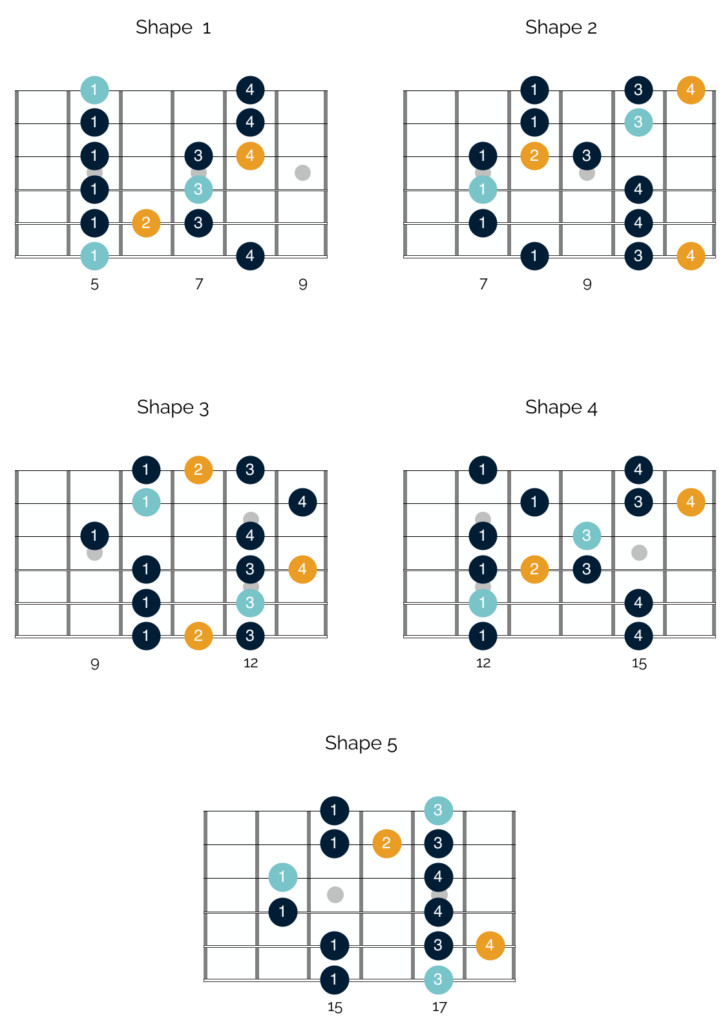

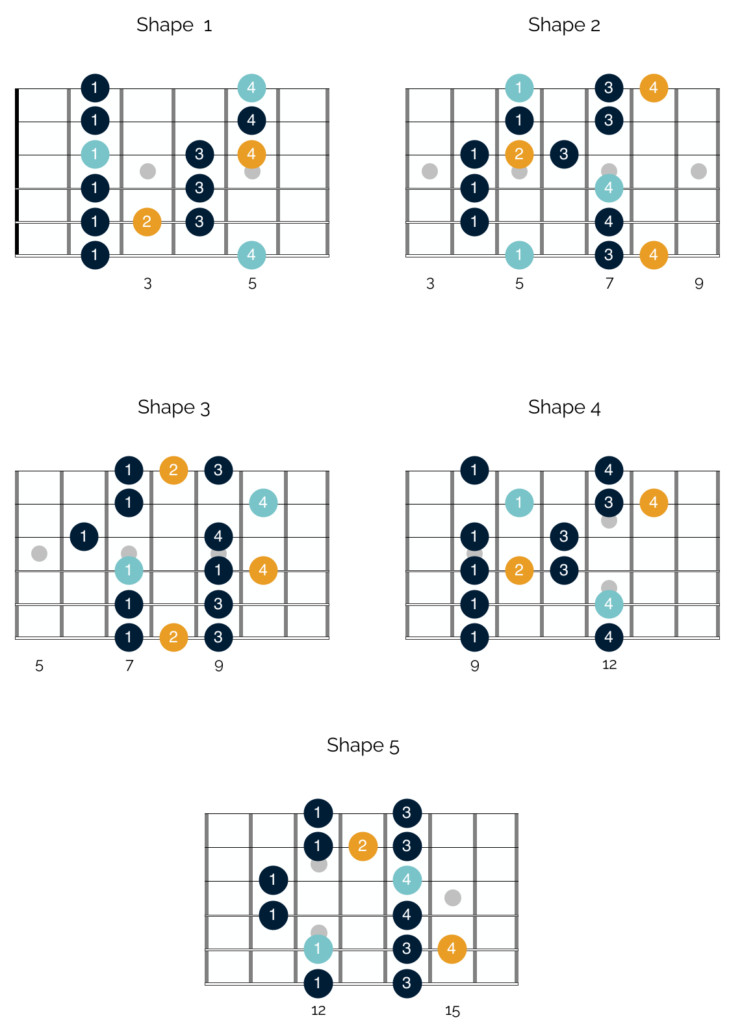

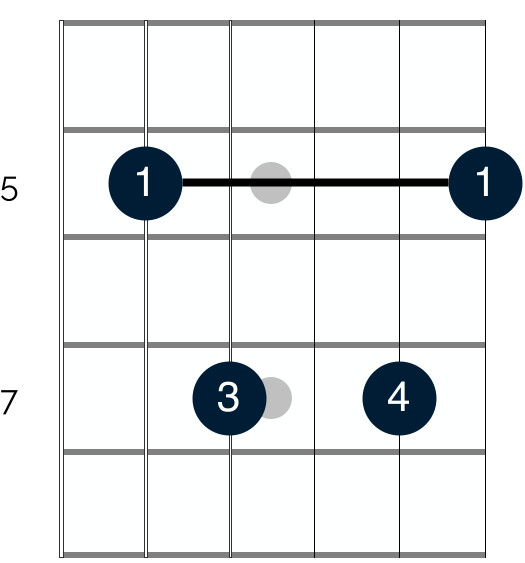

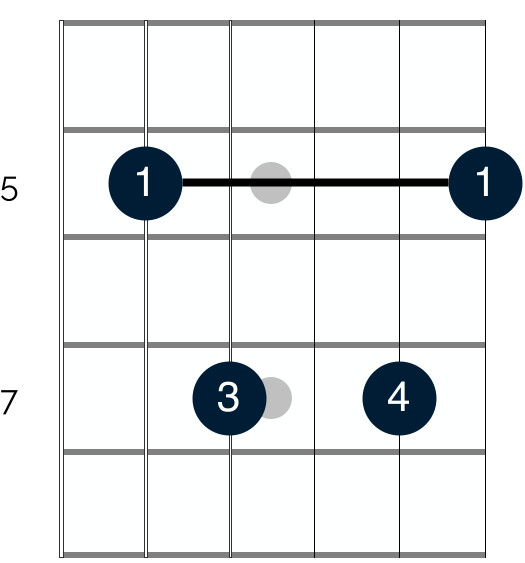

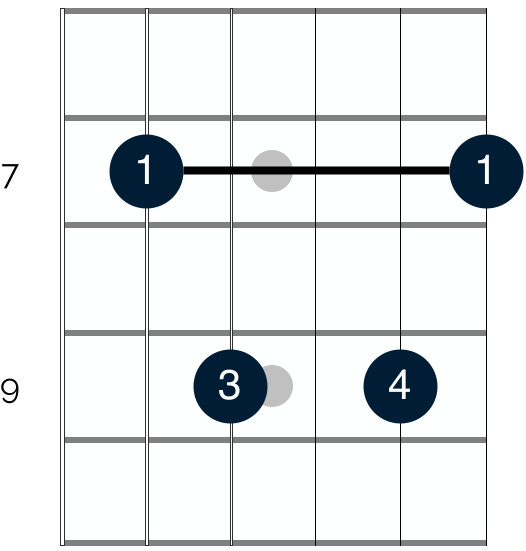

While these formulas are helpful, the scale shapes on the fretboard make it much clearer. Here are the A minor blues scale shapes:

In these diagrams, green notes are root and octave notes (A in this case), and blue notes are the added “blue notes.”

You can see that the shapes are almost identical to the minor pentatonic shapes. The only difference is the addition of the blue note.

Unleashing the Minor Blues Scale in Your Solos

The easiest way to think about using the minor blues scale is as a minor pentatonic scale with an extra flavor. Use it in any situation where you’d typically use the minor pentatonic.

If you’re new to this or need a refresher on when to use the minor pentatonic, here are the key scenarios:

Soloing in a Minor Key

The most straightforward application is: when a song is in a minor key, you can solo using the corresponding minor pentatonic or minor blues scale.

For example, in a B minor song, use the B minor pentatonic or B minor blues scale. In G minor, use the G minor pentatonic or G minor blues scale, and so on.

Bluesing it Up in a Major Key

In blues and blues rock, you can also solo using the minor pentatonic or minor blues scale over major chord progressions.

Theoretically, this seems counterintuitive. The minor third in minor pentatonic/blues scales clashes with the major third in major chords, creating dissonance. Traditional music theory advises against this.

However, blues music thrives on bending the rules.

As discussed in more detail in “Introduction to 12-Bar Blues,” blues songs often center on a 12-bar chord progression typically built from dominant 7th chords. These chords are unique because they blend major and minor elements, containing a root, major third, perfect fifth, and a minor seventh.

This minor seventh creates tension and an unresolved quality, a sound now deeply associated with the blues.

When soloing over these dominant 7th chord progressions, the minor pentatonic or minor blues scale works beautifully. The inherent major/minor clash in the chords diminishes the dissonance you’d normally get from playing minor scales over major chords.

You can confidently use minor pentatonic or minor blues scales over all chords in a major 12-bar blues progression – they will both sound fantastic.

The Magic of the Blue Note

While the minor blues and minor pentatonic scales are interchangeable, they aren’t identical. That single blue note makes a significant difference, introducing chromaticism and tension.

This tension is less prominent when solely using the minor pentatonic scale.

Part of the minor pentatonic’s popularity among guitarists is its versatility – it works in many contexts without creating harsh dissonance.

Listen to this example:

[Audio clip of A minor pentatonic over A minor chord]

The A minor pentatonic scale shape 1 over an A minor chord. Notice the lack of dissonance or tension. Holding or repeating any note within the minor pentatonic scale similarly lacks harshness. While some notes are better for emphasis, none will cause a jarring dissonance.

This holds true for 12-bar blues progressions and most situations where minor pentatonic scales are suitable. You’re generally safe from hitting truly unpleasant notes.

This is not the case with the minor blues scale. Listen to this:

[Audio clip of blue note (b5) from A minor blues scale over A minor chord]

The blue note (b5) at the 8th fret of the G string (shape 1 of A minor blues scale) over an A minor chord. You can hear the harsh, quite unpleasant dissonance.

Why Use the Dissonant Blue Note?

Given the harshness of the blue note, why even use the blues scale?

Precisely because of this dissonant sound.

Effective blues guitar is about conveying emotion. And manipulating tension is key to emotional expression in music. You build tension and then strategically release it.

Chromatic notes, like the blue note, are powerful tools for creating and resolving tension.

Finding the Right Balance with the Blue Note

As mentioned, minor blues and minor pentatonic scales are interchangeable. The key difference is managing the blue note effectively in the blues scale.

The secret is sparing use. Don’t linger on the blue note or let it ring out excessively, or you’ll get that grating sound from the audio example.

Instead, treat the blue note as a “passing note.”

Use it to transition between the other notes within the minor pentatonic scale. This creates momentary tension that resolves as you move past the blue note to a pentatonic scale tone.

This chromatic element adds amazing depth and sophistication to your lead playing.

The main pitfall is overusing the blue note. It’s like spice – a little adds flavor, but too much overwhelms the dish. Especially when learning, take a conservative approach. Less is more.

Minor Pentatonic vs. Minor Blues Scale: Lick Examples

To illustrate effective minor blues scale usage, here are 3 licks comparing minor pentatonic and minor blues scale versions. Each example has a bar of rest between licks (not in tab) for easier comparison. All licks are in A minor.

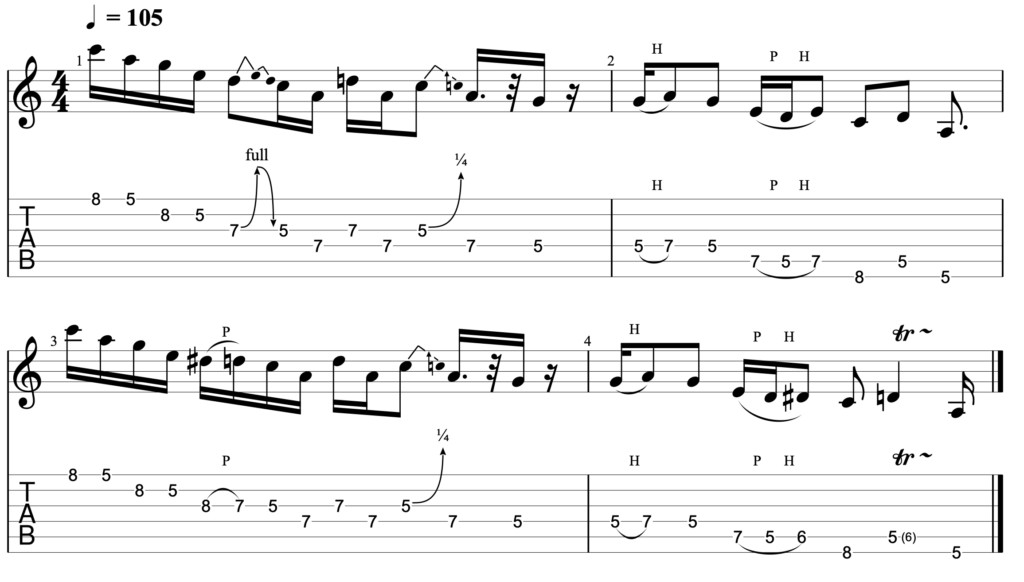

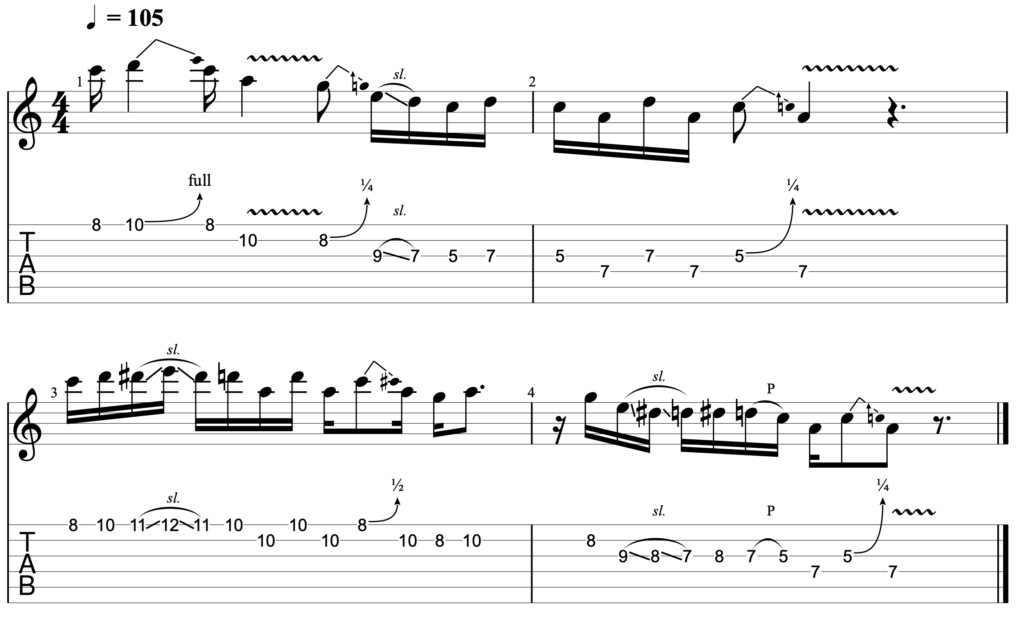

Lick 1

[Audio Clip Lick 1]

At 105 BPM, these licks demonstrate the difference. Lick 1 starts with a descending run based on minor pentatonic shape 1. The blues scale variation adds the blue note in the descending run and in the trill at the end.

Lick 2

[Audio Clip Lick 2]

At 105 BPM, Lick 2 shows a more obvious blue note use. It demonstrates building tension with the blue note through repetition, resolved by the bend at the lick’s end.

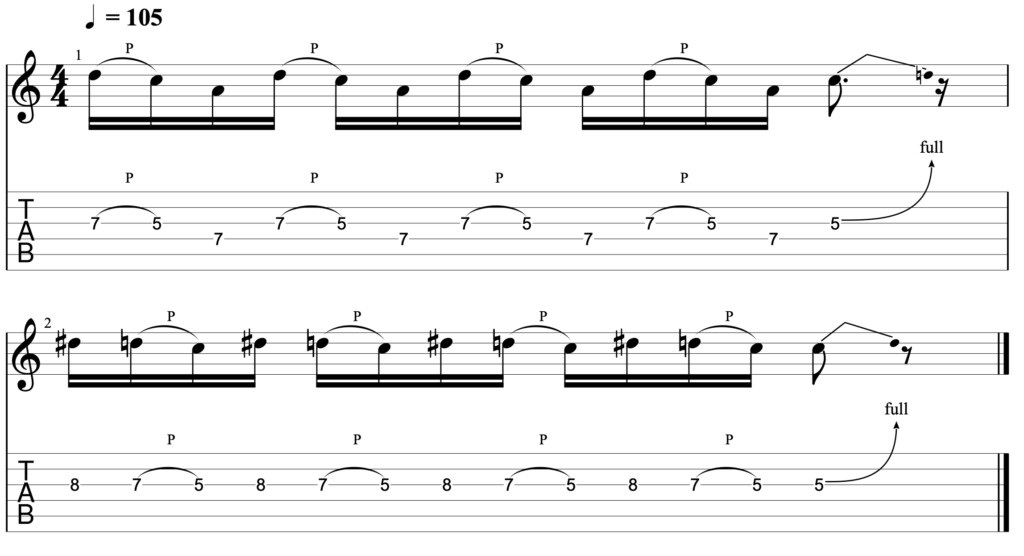

Lick 3

[Audio Clip Lick 3]

At 105 BPM, Lick 3 shows using the blue note to connect different fretboard positions. The blue note use is more deliberate and prominent, showing the feel it can create.

While in isolation, the blues scale licks might not sound dramatically different (except maybe lick 3), in a full solo, repeated blue note use will significantly alter your lead playing’s character.

Minor Blues Scale Recap: Practice Makes Perfect

We’ve covered a lot, so let’s pause and consolidate. It’s crucial to absorb these ideas one at a time. Before moving on, dedicate time to practicing and understanding the minor blues scale.

It’s better to spend a bit longer learning the minor blues scale thoroughly than to rush and not grasp its effective use.

When I first learned this scale, I focused solely on it for about 2 weeks. Here’s my practice approach:

- Scale Shapes: Play the scale shapes up and down the neck in all A minor positions. Use a metronome as described in Exercise 1 below.

- Backing Track Practice: Once comfortable with shapes and positions, play along to an A minor blues backing track.

- Scale Shape Improvisation: Start by playing the A minor blues scale shapes over the backing track, moving between positions across the neck.

- Improvisation and Position Changes: Then, improvise using the A minor blues scale, aiming to “meander” across the fretboard and connect different positions, becoming familiar with shapes across the neck.

- Blue Note Experimentation: Experiment with the blue note, adjusting your “go-to” licks to incorporate it. Understand the differences between minor blues and minor pentatonic scales and learn to use the blue note effectively, avoiding overuse.

- Key Transposition: After A minor, repeat the process in B minor, C minor, etc., until comfortable with minor blues scale positions in different keys.

Major Blues Scale: Expanding Your Blues Palette

Once you’re confident with the minor blues scale, you can explore the major blues scale.

This assumes you know major pentatonic scale shapes and usage.

If not, read “A Beginner’s Guide To The Major Pentatonic Scale” first. It covers major pentatonic scales, shapes, and applications.

Just as minor pentatonic and minor blues scales are closely related, so are major pentatonic and major blues scales.

The major blues scale is also a major pentatonic scale with one added note.

In the major blues scale, the added note is the b3 (flat third), another blue note. All other notes remain the same as the major pentatonic.

Major pentatonic scale structure:

1 2 3 5 6

Major blues scale structure:

1 2 b3 3 5 6

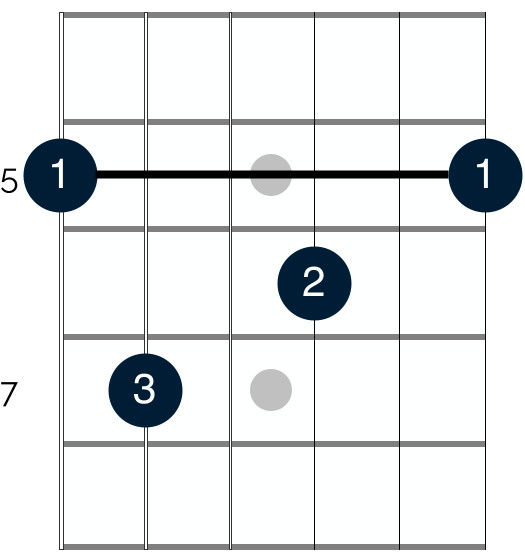

Here are the major blues scale shapes on the fretboard:

Again, green notes are root/octave (A), and blue notes are the added blue notes.

The shapes are almost identical to major pentatonic shapes, with only the blue note added.

The Blue Note in the Major Blues Scale: A Different Flavor

While minor and major blues scale shapes are similar, the blue note’s function differs slightly.

In the minor blues scale, the blue note adds significant tension. It’s a completely new note not in either pentatonic scale.

The major blues scale’s blue note is different. It’s not a “new” note; it’s the b3, a note already present in the minor pentatonic scale.

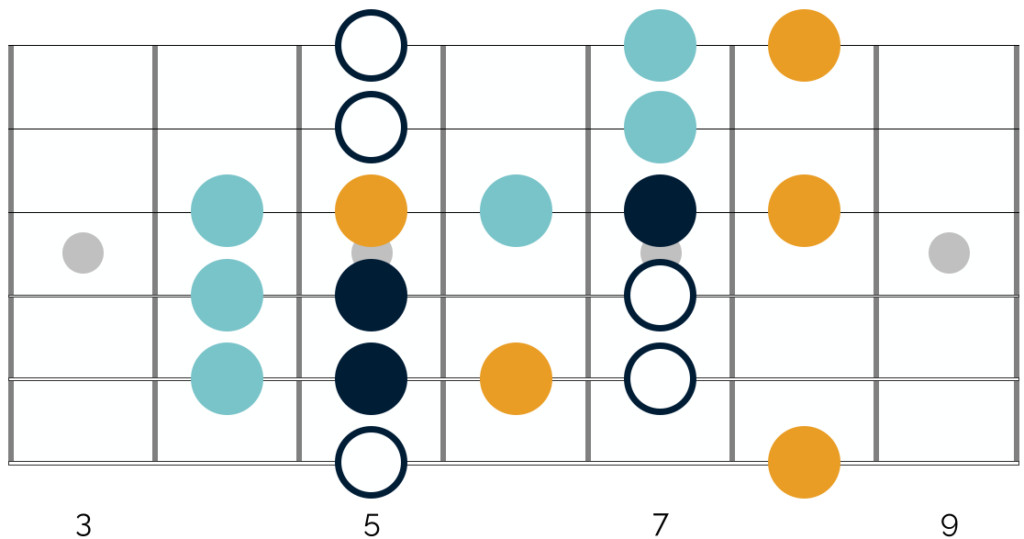

Let’s examine this overlap:

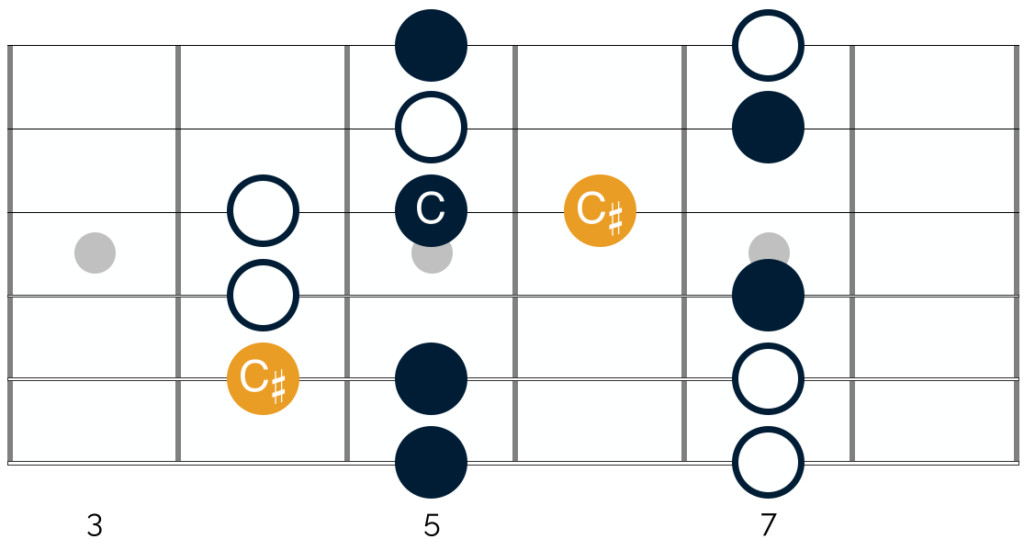

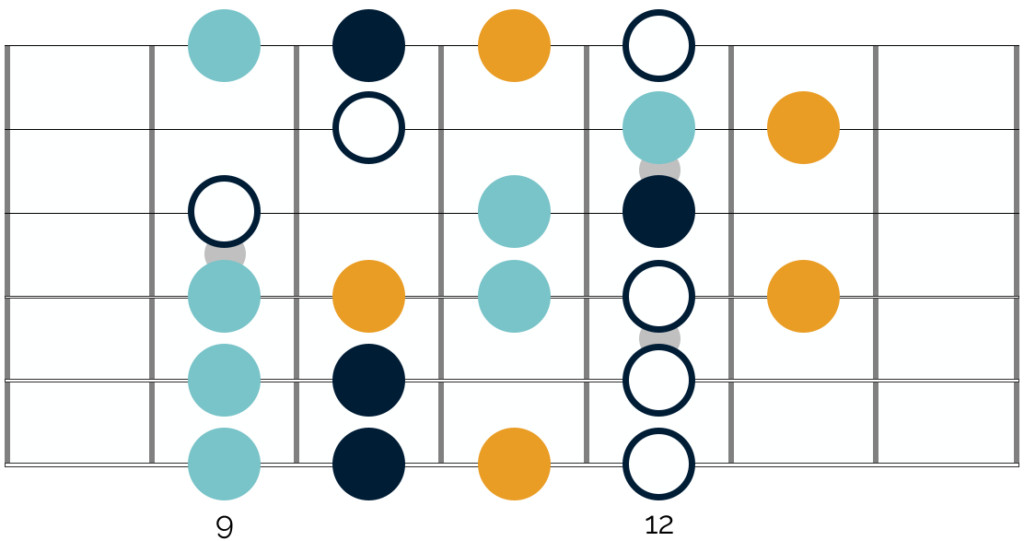

This diagram shows A major and minor blues scale shape 1 and 2 overlap. White notes are in both scales. Dark blue is minor blues only, light blue is major blues only, and yellow are blue notes in both.

Compare this to minor pentatonic scale shape 1:

Yellow highlights the blue notes from major blues scale shape 2. These notes are already in the minor pentatonic scale.

So, if you’ve mixed minor and major pentatonic scales, you’ve likely already played the major blues scale without realizing it.

Using the Major Blues Scale: Intentional Blues

The good news is you’ve likely already played the major blues scale. The next step is using it more intentionally.

Two key elements to consider: understanding major pentatonic scale use and applying those principles to the major blues scale.

Like minor pentatonic and minor blues scales, major pentatonic and major blues scales are interchangeable. However, using major pentatonic (and thus major blues) scales effectively is slightly trickier than using their minor counterparts.

There are a few more “rules” to follow. These rules apply to both major pentatonic and major blues scales.

The two main rules are:

1. Use Over Major & Dominant Chord Progressions

Minor pentatonic and minor blues scales are versatile because they work over both major and minor chord progressions in most blues and rock contexts.

This defies music theory, but it works brilliantly and defines the blues sound.

The opposite is not true for major pentatonic and major blues scales. Playing them over minor chord progressions will sound bad due to clashes between major scale notes and minor chords, creating harsh dissonance.

Use major pentatonic and major blues scales only over major chord progressions and dominant chord progressions.

If you’re unfamiliar with dominant chords, read “Dominant 7th Chords” for a detailed explanation of dominant 7th chords, common in 12-bar blues.

2. Avoid The IV Chord

The second reason guitarists struggle with major pentatonic and major blues scales is difficulty playing them over the entire 12-bar blues progression.

“Introduction to 12-Bar Blues” explains 12-bar blues form in detail. Briefly, a typical 12-bar blues progression uses I, IV, and V chords in a key.

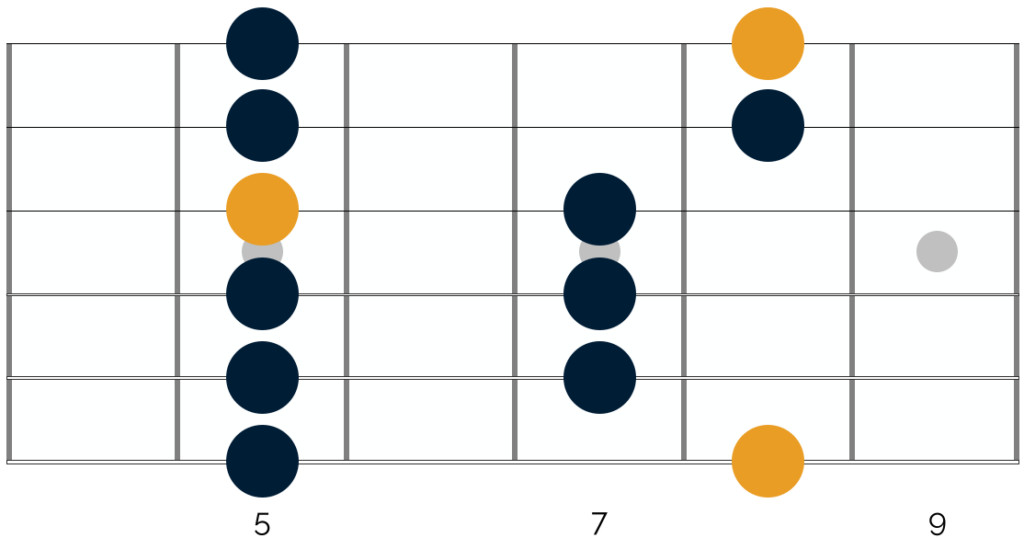

In A, this is A7, D7, and E7. Let’s focus on the D7 (IV) chord. One common voicing is:

[

Playing major pentatonic or major blues scales over this chord is tricky due to clashes. In A major, the major pentatonic scale has C#. This clashes with the C in the D7 chord, creating dissonance:

Dark blue dots are D7 chord notes. Many major pentatonic/blues scale notes in this position are also in the chord. White circles are added major blues scale notes (not in the chord). Yellow notes are in major pentatonic/blues scales and clash with the chord.

[Audio clip of C# (major pentatonic) against C (D7 chord)]

As you can hear, it doesn’t sound good. While you could play the scale and avoid that note, it’s difficult.

Mixing Minor & Major Blues Scales – Part 1: Chord-by-Chord Strategy

The clash between major blues scale notes and the IV chord in a 12-bar blues isn’t musically useful. It’s just discordant and should be avoided.

These rules might seem complex, but they become easier with practice.

Here’s a guide to using major blues scales alongside minor blues scales in a 12-bar blues progression in A (adaptable to other keys):

A7 (I Chord)

Over the I chord (A7), you can use either minor or major blues scales.

Both sound great; the choice depends on your desired feel.

Opening with the major blues scale creates a brighter, more upbeat feel.

Starting with the minor blues scale creates a heavier, edgier feel.

You can also mix both scales over the I chord, as we’ll explore further.

D7 (IV Chord)

[

When the progression moves to the IV chord (D7), use the minor blues scale. In A major, the A minor blues scale is your best bet.

You could also use the minor blues scale related to the IV chord (D minor blues scale over D7).

However, if you’re starting out, stick with the A minor blues scale over the D7 chord to simplify things and focus on mastering the basic application first.

E7 (V Chord)

The last chord in a typical 12-bar blues progression in A is E7 (V chord).

Similar to the I chord, you can use both major and minor blues scales here, depending on the feel you want.

You also have the option to use scales related to the chord itself: E minor blues scale or even E major blues scale.

So, over the E7 chord, you have a range of choices:

- A major blues scale

- A minor blues scale

- E major blues scale

- E minor blues scale

Again, if you’re new to this, keep it simple. Stick with the A blues scale (major or minor versions) and experiment with switching between them, rather than immediately trying to change to E blues scales.

Mixing Minor & Major Blues Scales – Part 2: Chromatic Runs

If you’ve already mixed minor and major pentatonic scales, the chord-by-chord approach is likely familiar.

Once you’re comfortable using each blues scale version appropriately, you can take it a step further.

Let’s revisit the major and minor blues scale overlap:

Still in A, this diagram shows the fretboard position where minor blues scale shape 3 overlaps with major blues scale shape 4.

White notes are in both scales, dark blue is minor blues only, light blue is major blues only, and yellow are blue notes in both.

Combining these scales gives you a wide note selection. Notice on some strings, there are 4 or even 5 notes in a line.

This allows for ascending and descending chromatic runs, adding a sophisticated, jazzy feel when used correctly.

Here’s a lick example:

[Audio clip of chromatic lick example]

This short lick has a high density of chromatic runs, perhaps more than typically used in a blues context.

However, it demonstrates how to incorporate these ideas. Experiment with phrases and licks in your solos to find a balance that suits your style.

Blues Scales in Context: Song Examples

To provide more context, here are famous riffs and solos using blues scales:

| Song | Artist | Guitarist | Key | Scale Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Pride and Joy” | Stevie Ray Vaughan | Stevie Ray Vaughan | E | Major Blues Scale |

| “Heartbreaker” | Led Zeppelin | Jimmy Page | E | Minor Blues Scale |

| “Walk This Way” | Aerosmith | Joe Perry | C | Minor Blues Scale |

These are just a few examples. Countless blues and blues rock songs feature solos and riffs built on blues scales.

Listen to these songs and try to identify the blue notes in the solos and riffs. This will help you develop an ear for how blues scales sound in a musical context, which is invaluable when creating your own solos and improvisations.

Practicing Blues Scales: Exercises for Mastery

Given the importance of blues scales in blues and blues rock, make them a regular part of your guitar practice routine.

Here are two exercises I use regularly:

Exercise 1: Slow and Steady Metronome Practice

This exercise is excellent for beginners and those new to blues scale shapes. Play scale shapes slowly to a metronome at the slowest manageable tempo.

This serves two purposes:

- Shape Consolidation: Reinforces minor and major blues scale shapes across the guitar neck.

- Rhythmic Precision: Develops rhythmic accuracy. While speed is great (and discussed in “7 Guitar Exercises To Play Faster”), timing is crucial for great guitar playing. Good timing helps you “lock in” to the groove and play “in the pocket.”

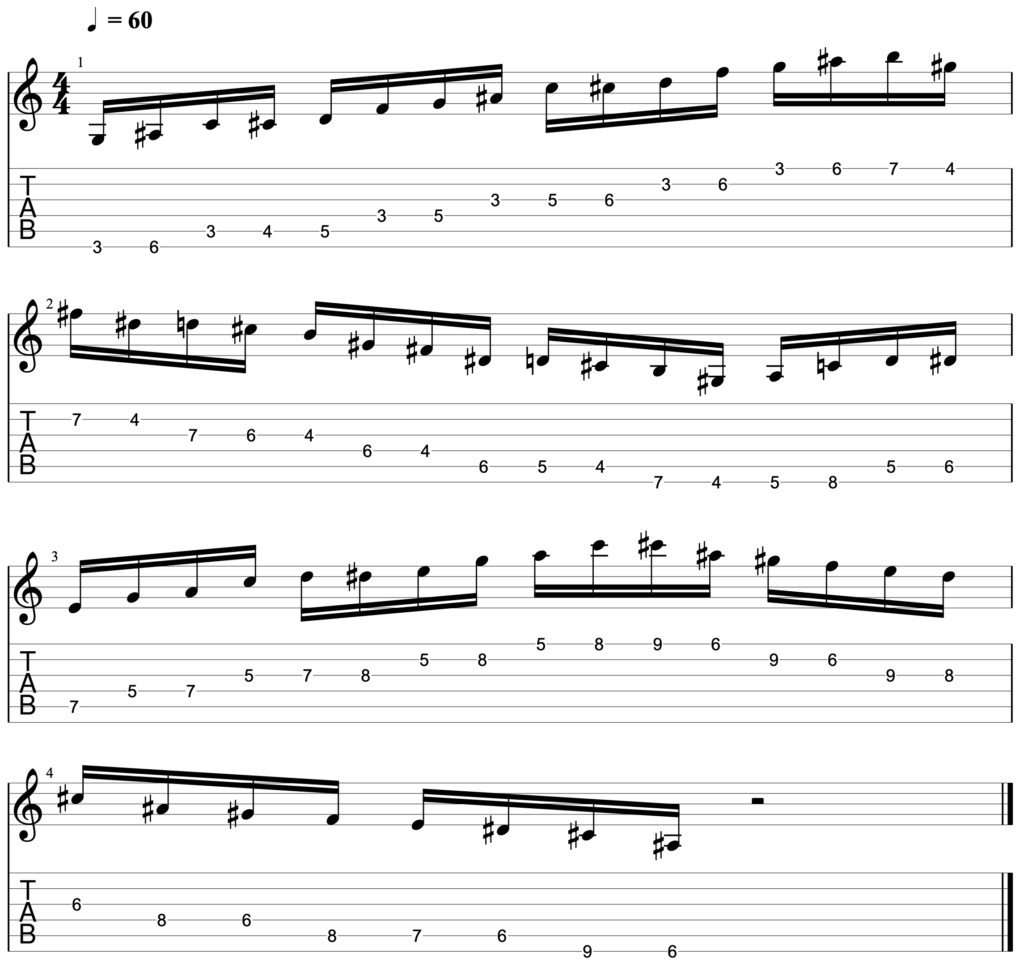

To practice, set a metronome to 60-70 BPM. Play major and minor blues scale shapes (shapes are the same, positions differ), playing two notes per metronome click. Practice in various keys.

Start at a tempo where you can play comfortably in time, aiming for perfect synchronization with the metronome click.

Once mastered, decrease the BPM by a couple of beats and repeat. Continue lowering the BPM as you improve. Slower tempos become surprisingly challenging.

I often use this as a warm-up to get fingers moving and improve timing and rhythm.

Exercise 2: Chromatic Scale Runs Across the Fretboard

This exercise is slightly more technical. Play each blues scale shape chromatically up and down the fretboard. Here’s how to do it with blues scale shape 1:

Start at the 3rd fret with shape 1. Move up the neck as shown to the 15th fret, then immediately descend back to the 3rd fret. Repeat for all blues scale shapes.

Use a metronome, playing four notes per click this time.

[Audio clip of Exercise 2 at 60 BPM]

Like Exercise 1, this reinforces scale shapes and fretboard familiarity.

Additionally, it builds speed and stamina in both picking and fretting hands, as you move continuously between shapes without pausing.

Choose a BPM that’s fast but manageable, pushing yourself without sacrificing accuracy.

Increase the BPM as you improve.

Putting It All Together: Blues Scale Mastery

There’s a lot to absorb about blues scales. If you feel overwhelmed, remember these key points:

- Minor and Major Blues Scales: Both exist. Minor blues scale is minor pentatonic + blue note. Major blues scale is major pentatonic + blue note.

- Chromatic Blue Note: The added “blue note” in both scales is chromatic, adding tension and bluesy flavor.

- Minor Blues Scale Versatility: Use minor blues scales anywhere you’d use minor pentatonic scales.

- Major Blues Scale Versatility: Use major blues scales anywhere you’d use major pentatonic scales (and often minor pentatonic scales too, except over the IV chord in a 12 bar blues).

- Blue Note Sparingly: Use the blue note to add tension and chromaticism. Overuse diminishes its impact.

Final Advice: Break down learning blues scales into manageable steps. Don’t try to absorb everything at once.

Start with the minor blues scale, getting comfortable using it in place of the minor pentatonic. Then, focus on the major blues scale. Finally, work on combining both scales effectively in your playing.

Do this, and you’ll be amazed at how much bluesier and more varied your solos become. You’ll add edge, depth, and authentic blues emotion to your guitar playing.

Good luck! Let me know how you progress. If you have further questions, reach out via the comments or email me at [email protected]. I’m here to help!

References

YouTube, Andys Lab, Guitar Music Theory, Music Stack Exchange, Your Guitar Academy, Jazz Guitar

Images

Image of Stevie Ray Vaughan – ©RTBusacca / MediaPunch (Taken from Alamy)

Donner Deal