“My guitar is not a thing,” Joan Jett famously stated. “It is an extension of myself. It is who I am.” The guitar resonates as a universal instrument, deeply primal yet profoundly expressive. While anyone can quickly learn a few chords, a lifetime is insufficient to explore its boundless potential. This is precisely what makes contemplating the essence of a great guitarist so captivating.

Rolling Stone initially unveiled its list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists in 2011, curated by a panel of seasoned musicians, largely from the classic rock era. Now, in an expansive update, Rolling Stone‘s editors and writers present a new list, extending to 250 guitarists, aiming to showcase the instrument’s vast evolution and impact across genres and generations.

Guitar players often achieve iconic status, rivaling even the lead singers of their bands. While legendary guitar gods like Jimmy Page, Brian May, and Eddie Van Halen are pivotal figures, this new list seeks to portray a broader narrative of the guitar’s journey. Spanning from folk pioneer Elizabeth Cotten, born in 1893, to indie-rock sensation Lindsey Jordan, born in 1999, the compilation encompasses a rich tapestry of genres. Rock, jazz, reggae, country, folk, blues, punk, metal, disco, funk, bossa nova, bachata, Congolese rumba, and flamenco are all represented, highlighting the instrument’s versatility. From unparalleled virtuosos such as Pat Metheny, Yvette Young, and Steve Vai to raw, primal players like Johnny Ramone and Poison Ivy of the Cramps, the list celebrates diversity in style and approach. It also acknowledges both mainstream stars like Prince, Joni Mitchell, and Neil Young, and unsung heroes like Memphis soul maestro Teenie Hodges and smooth-rock virtuoso Larry Carlton.

Recognizing the collaborative nature of music, the list includes entries for dynamic duos such as Kim and Kelley Deal of the Breeders, Adrian Smith and Dave Murray of Iron Maiden, and other synergistic pairings. The primary criterion remained focused on six-string players, acknowledging the vast landscape of guitar artistry.

In compiling this list, Rolling Stone prioritized substance over style, emotion over technical perfection, innovation over imitation, and originality over refinement. The emphasis was placed on artists who channeled their unique talents into crafting exceptional songs and groundbreaking albums, rather than solely on technical prowess.

As modern blues luminary Gary Clark Jr. aptly put it, “I don’t know if I want to get too far off the path — I don’t want to get lost in the forest — but I like to wander out a bit and adventure.” This spirit of exploration and adventure embodies the essence of the greatest guitar players celebrated in this list.

Elmore James

Elmore James playing blues guitar, showcasing his slide technique and electric pickup, circa 1960

Elmore James playing blues guitar, showcasing his slide technique and electric pickup, circa 1960

Mississippi-born Elmore James, a singer and guitarist, is synonymous with one unforgettable guitar lick: the rhythmic, descending slide riff that defines his 1951 rendition of Robert Johnson’s “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom.” “But it was a great lick,” notes slide guitar virtuoso Derek Trucks. “There was something unleashed in his playing, that acoustic guitar amplified with an electric pickup. Even when he sang, his voice resonated through that electric pickup.” James further solidified his signature sound with captivating variations of this lick in tracks like “Shake Your Moneymaker” and “Stranger Blues.” These songs became foundational standards of the blues revival after his untimely passing in 1963. James’ distinctive tone resonated deeply, inspiring countless guitarists. Robbie Robertson recounted, “I practiced 12 hours a day, relentlessly, until my fingers bled, striving to replicate Elmore James’ sound. Then, someone revealed to me that he played with a slide.” —R.T.

Key Tracks: “Dust My Broom,” “The Sky Is Crying”

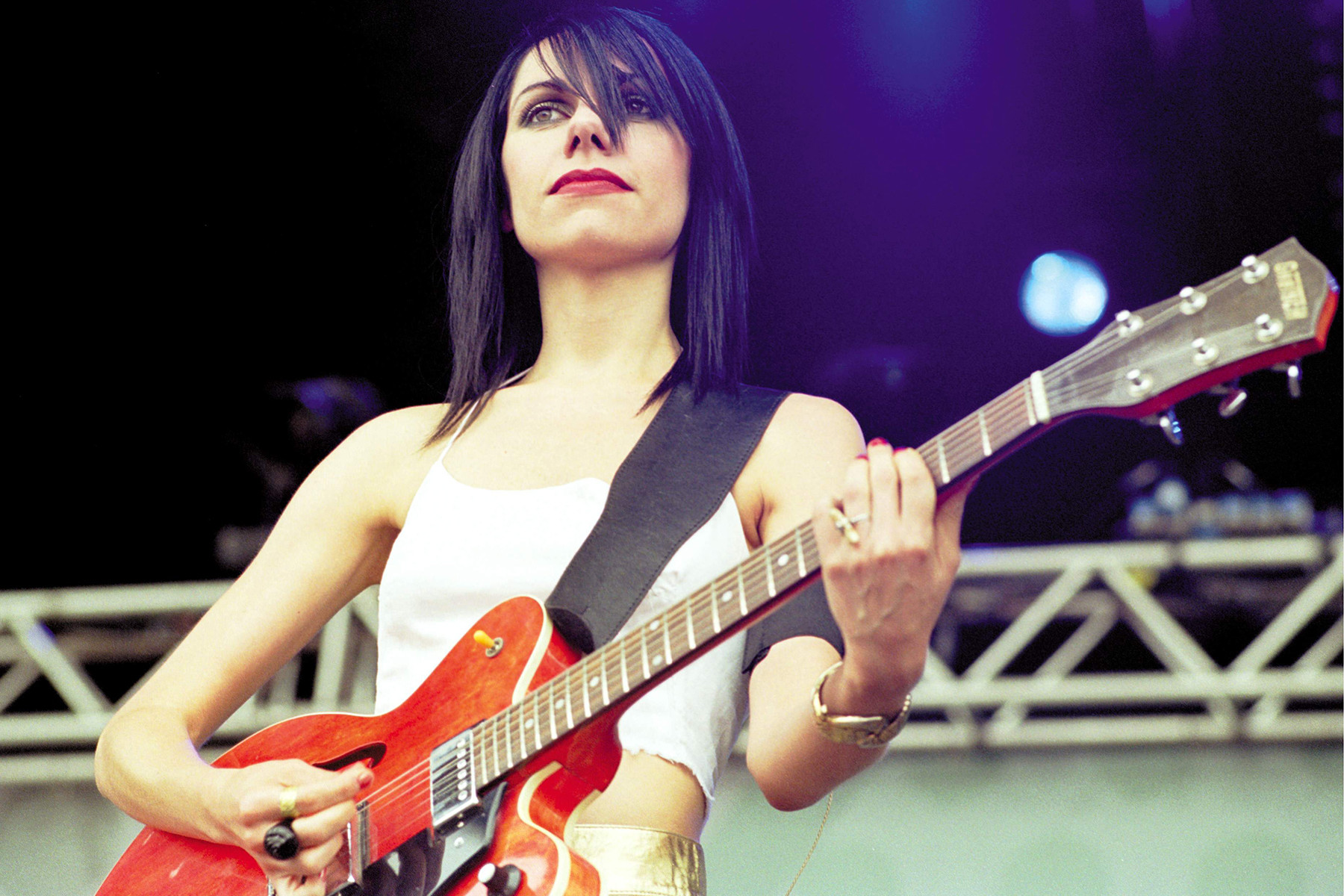

PJ Harvey

PJ Harvey performing live in Belgium in 2001, wielding her guitar with raw energy and emotion

PJ Harvey performing live in Belgium in 2001, wielding her guitar with raw energy and emotion

“I often reflect on the moment I first held a guitar, around 16 or 17,” Polly Jean Harvey shared with The New Yorker. “Before that, my expression was primarily through words. Discovering I could fuse words with music felt like the unlocking of gates, a surge of pure joy.” This creative spark was palpable in PJ Harvey’s seminal early albums, Dry and Rid of Me, where her guitar work was characterized by raw, jagged intensity, used as a visceral weapon. Three decades later, her playing has evolved into a more fluid style, yet remains intensely emotive, as she continuously extracts new sonic textures from the instrument. “I truly have no desire to simply revisit past creations,” she explained. “The thrill lies in uncovering something that feels entirely novel to my ears.” —M.J.

Key Tracks: “Missed,” “Autumn Term”

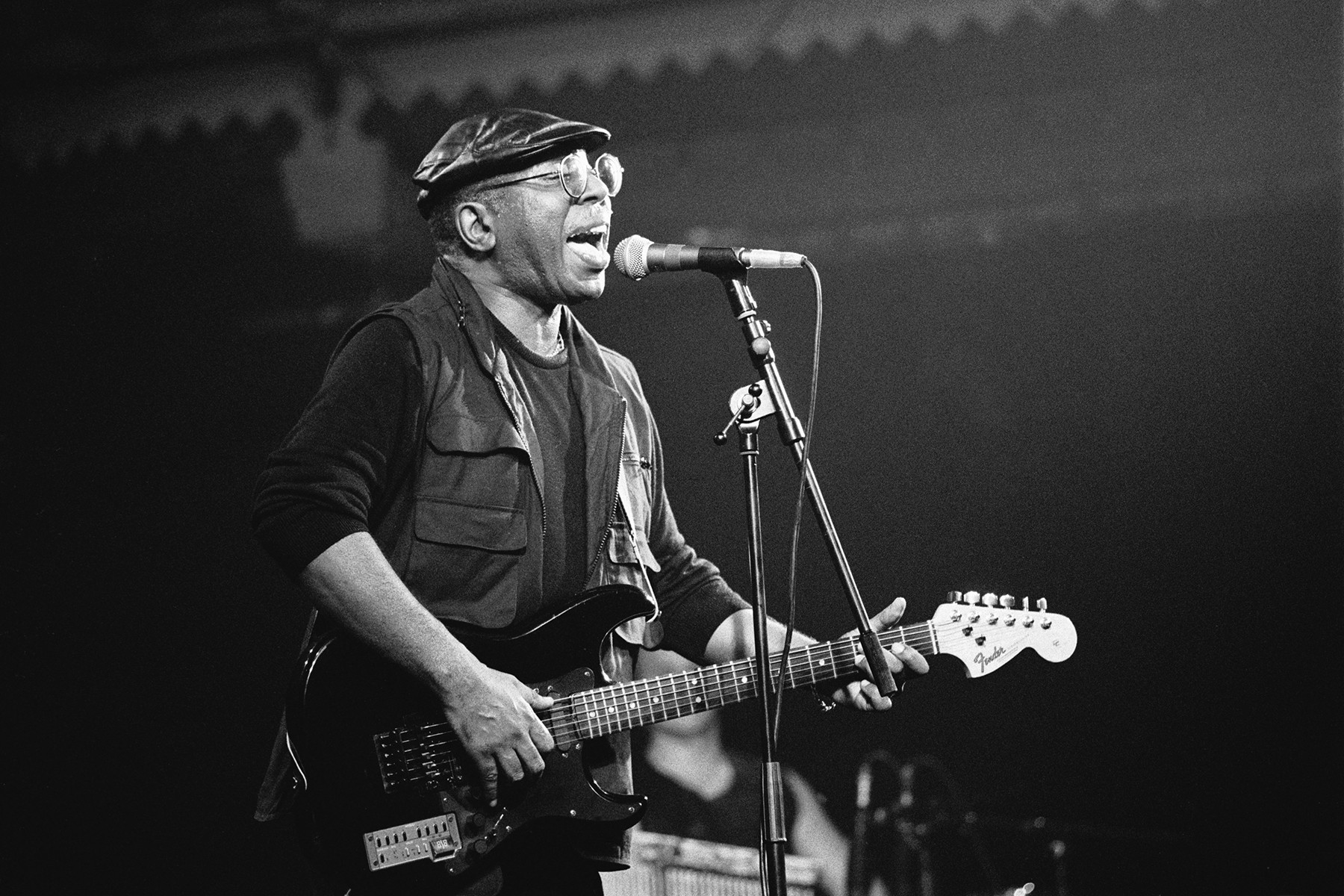

Curtis Mayfield

Curtis Mayfield singing and playing guitar at Paradiso, Amsterdam in 1990, showcasing his soulful and melodic guitar style

Curtis Mayfield singing and playing guitar at Paradiso, Amsterdam in 1990, showcasing his soulful and melodic guitar style

The late Curtis Mayfield stands as a titan of American soul music – a masterful singer, songwriter, and producer. He was also a subtly revolutionary guitarist, whose smooth, flowing melodies and fills, evident in The Impressions’ “Gypsy Woman,” profoundly influenced Jimi Hendrix, particularly in his psychedelic ballads. “In the Sixties, every guitarist aspired to play like Curtis,” George Clinton asserted. Mayfield later redefined his guitar approach for his solo career in the Seventies, crafting his new sound around flickering funk rhythms and sparse, expressive, wah-wah infused lead lines, as heard on his Superfly soundtrack and chart-toppers like “Move on Up.” His liquid chord progressions proved challenging for other musicians to emulate, partly because Mayfield predominantly played in an open F-sharp tuning. “Being self-taught, I never deviated from it,” he revealed. “It became a source of pride, knowing that regardless of a guitarist’s skill, they’d struggle to play my guitar.” —D.W.

Key Tracks: “Gypsy Woman,” “Move on Up,” “Freddie’s Dead”

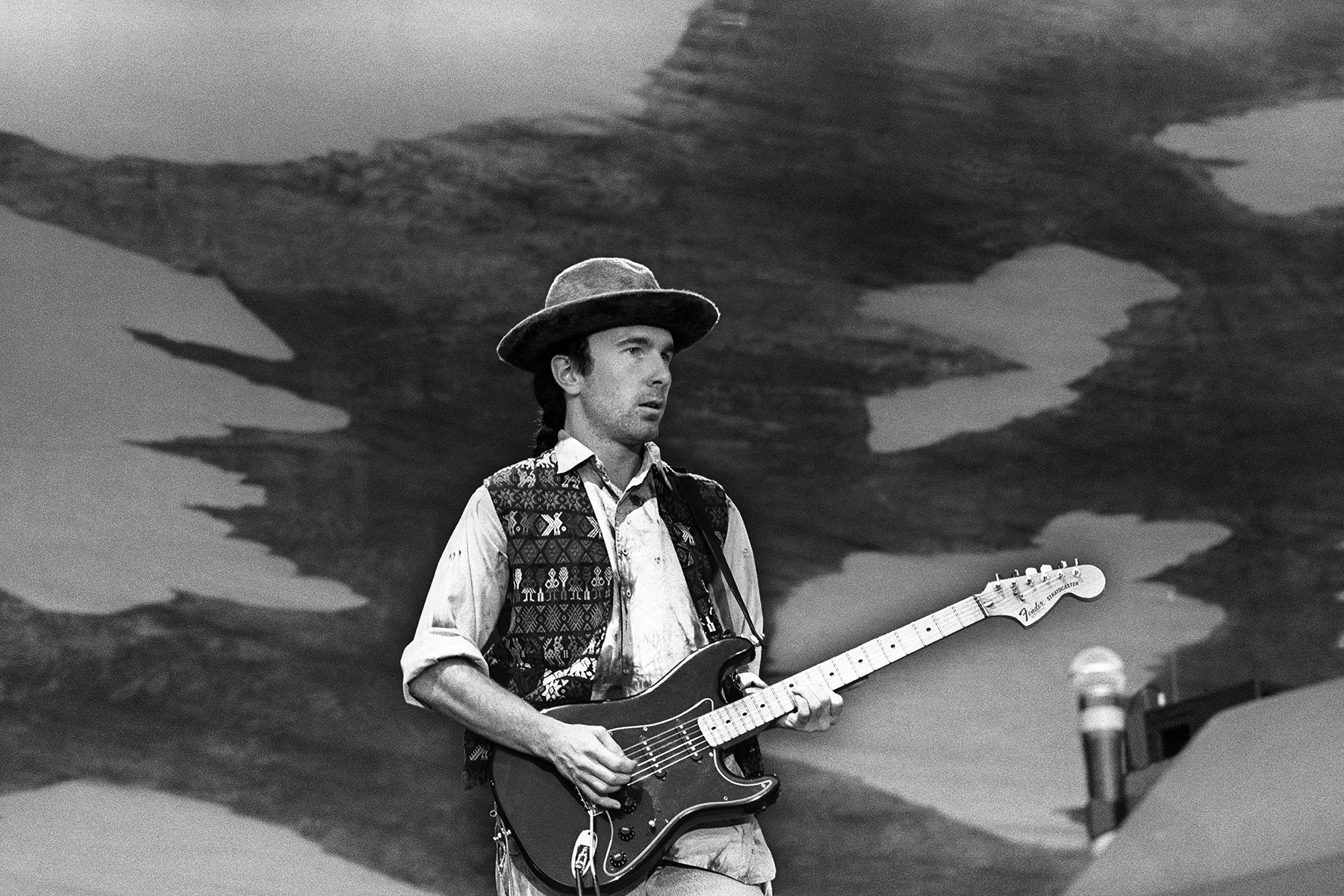

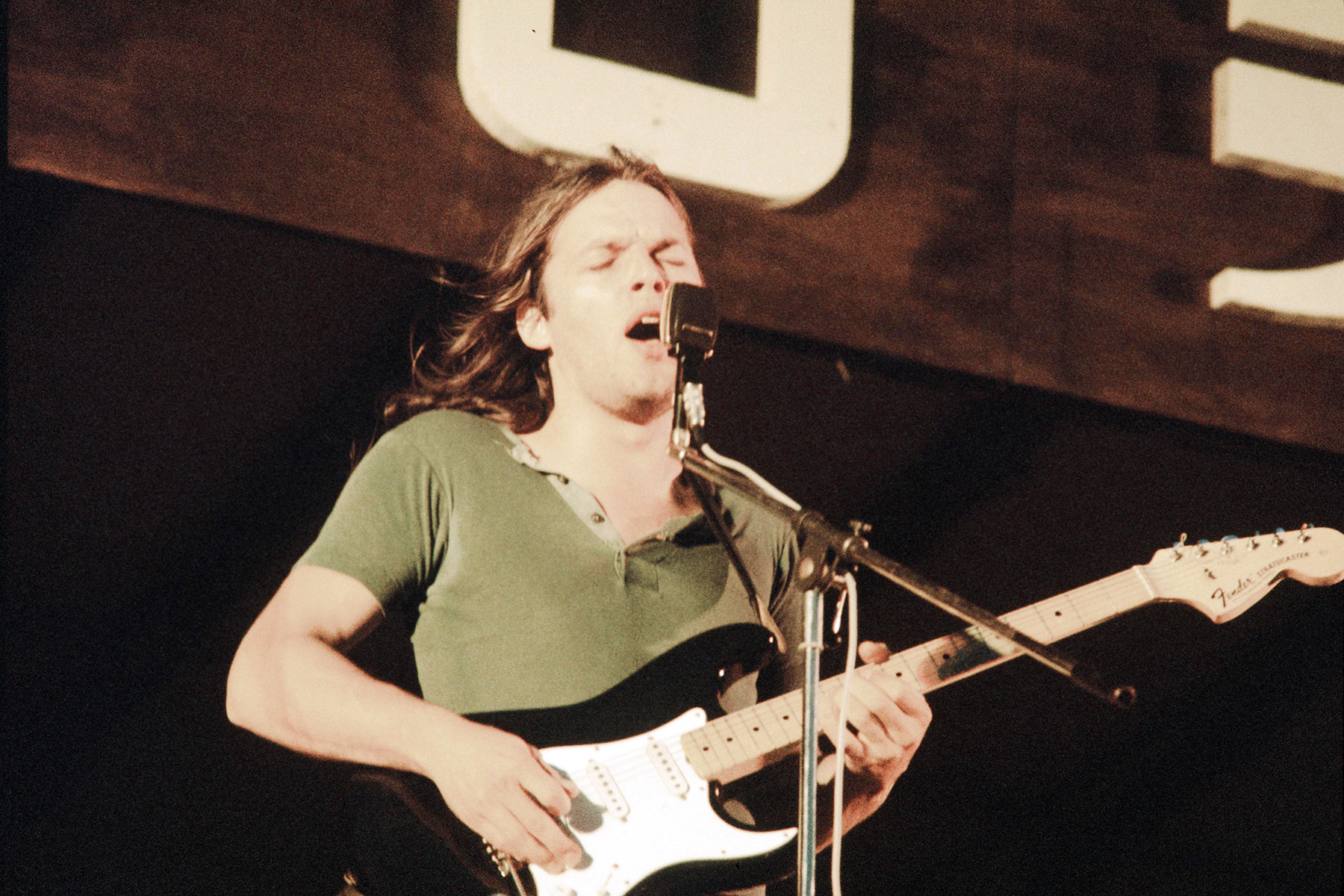

The Edge

The Edge playing a Fender Stratocaster on stage during U2's Joshua Tree Tour in Rotterdam, 1987, highlighting his innovative use of effects

The Edge playing a Fender Stratocaster on stage during U2's Joshua Tree Tour in Rotterdam, 1987, highlighting his innovative use of effects

As a young guitarist in the Seventies, The Edge immersed himself in a diverse range of genres, from punk and new wave to funk, blues, and R&B. He synthesized these influences into a distinctive sound within U2’s early work, ingeniously employing delay, echo, and reverb to forge a sonic landscape entirely his own. “I’m not a musician grounded in theory, nor a writer who is,” he shared with Rolling Stone in 2016. “I’m a hands-on musician, approaching music with a sense of naiveté. I thrive when I’m swept away by the unfolding sounds. Sonics are my muse; I’m a far superior guitarist when the sound is compelling.” The Edge refined his signature sound on The Joshua Tree, before embarking on a sonic reinvention in the Nineties, incorporating krautrock and club music elements. “Few guitarists can be identified by chords alone,” observed Joe Bonamassa. “The Edge is one—with a single strum and inflection.” —A.G.

Key Tracks: “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” “Where the Streets Have No Name”

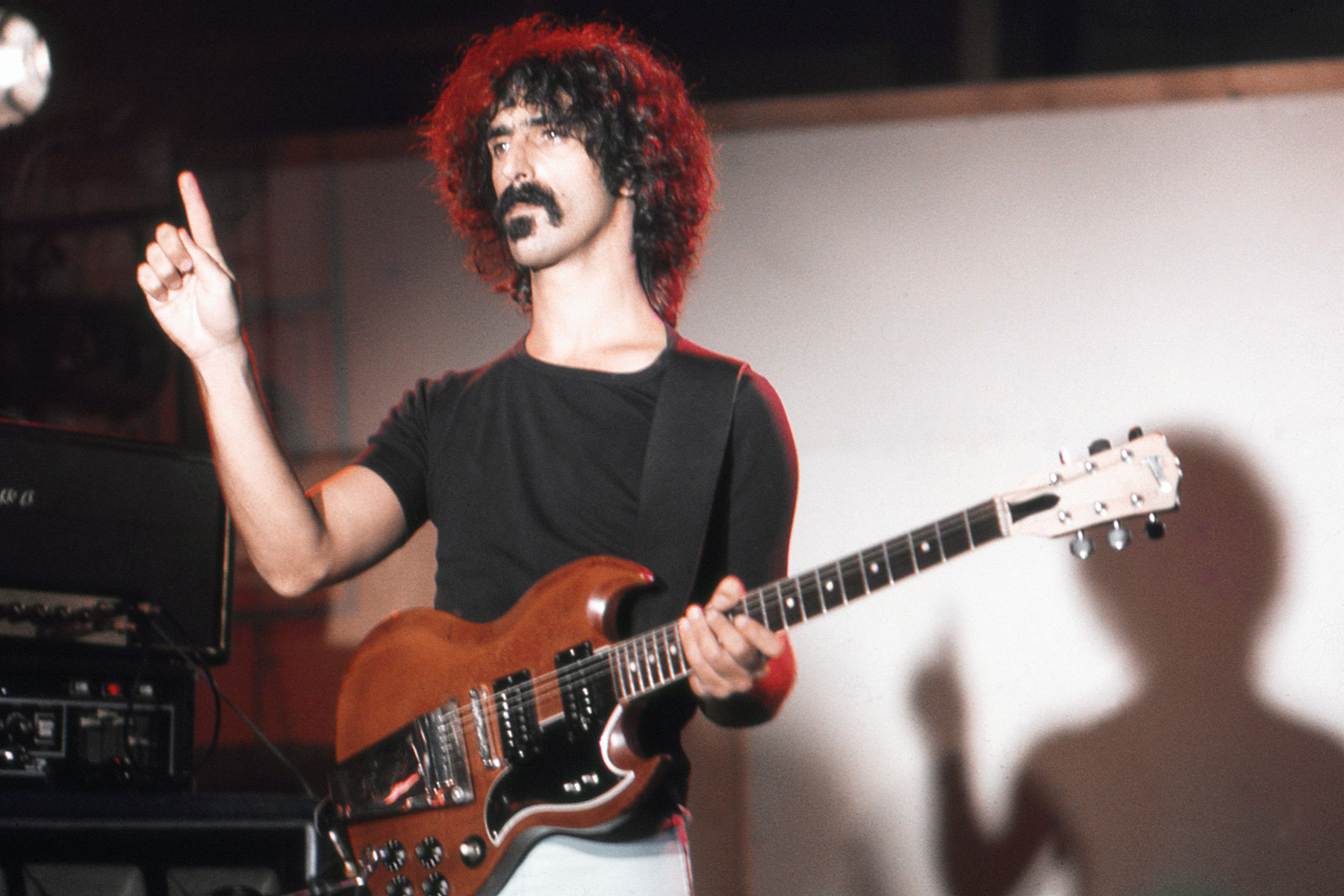

Frank Zappa

Frank Zappa in his studio in Los Angeles, 1974, surrounded by his musical equipment and showcasing his experimental approach

Frank Zappa in his studio in Los Angeles, 1974, surrounded by his musical equipment and showcasing his experimental approach

“When I was learning guitar, I was consumed by that album,” Phish’s Trey Anastasio reflected in 2005, referring to Frank Zappa’s 1981 compilation of complex and blistering solos, Shut Up ‘n’ Play Yer Guitar. “He explored every conceivable guitar boundary in ways unmatched by others.” As the undisputed leader of his ensembles, including the iconic Mothers of Invention lineups, Zappa masterfully fused doo-wop, urban blues, big-band jazz, and orchestral modernism with unwavering vision. As a guitarist, he drew from this eclectic palette, improvising with unrestrained passion and delight. His solo in “Willie the Pimp,” from 1969’s Hot Rats, is a sprawling studio jam, a feast of raw distortion, wah-wah textures, and agitated blues progressions. —D.F.

Key Tracks: “Willie the Pimp,” “In-a-Gadda-Stravinsky”

Steve Cropper

Steve Cropper in the UK, showcasing his understated yet perfect rhythm guitar style and soulful touch

Steve Cropper in the UK, showcasing his understated yet perfect rhythm guitar style and soulful touch

Peter Buck hailed Steve Cropper as “possibly my all-time favorite guitarist. You rarely hear him unleash a flashy solo, yet his playing is consistently impeccable.” Cropper is the secret ingredient in numerous iconic rock and soul songs. In his teens, he scored his first hit (“Last Night”) with the Mar-Keys. He then spent much of the Sixties with Booker T. and the MG’s, the legendary Stax Records house band, contributing to hits by Carla Thomas, Otis Redding, and Wilson Pickett. Since then, his minimalist, soulful guitar work has graced recordings by a multitude of rock and R&B artists, including a stint with the Blues Brothers band. Consider the intro to Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man,” the explosive bent notes in Booker T.’s “Green Onions,” or the intricate guitar fills in Redding’s “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay”—all bear Cropper’s signature sound, the very essence of soul guitar. “Center stage holds no appeal for me,” Cropper states. “I’m a band member, always have been.” —D.W.

Key Tracks: “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” “Green Onions,” “Soul Man”

Johnny Ramone

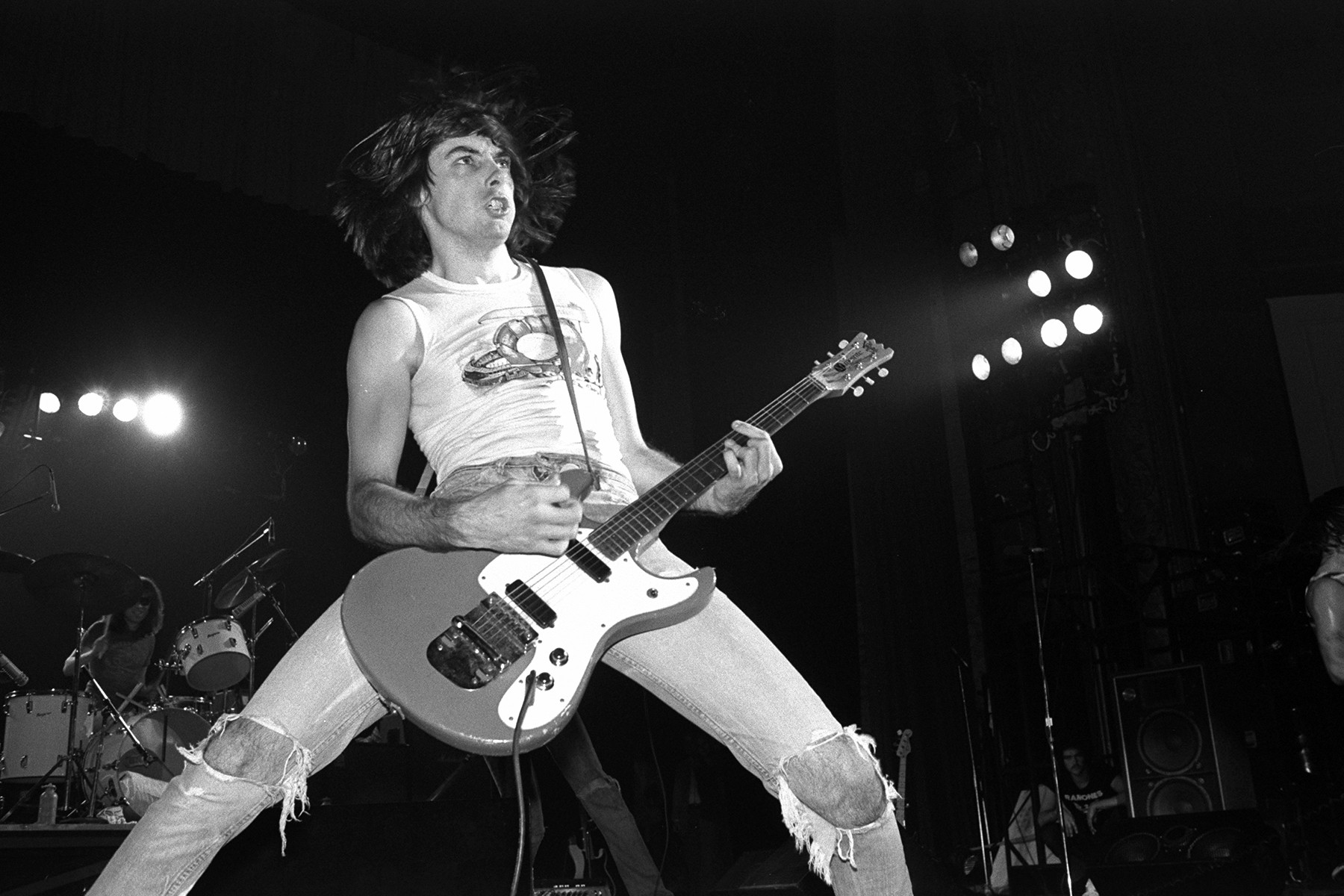

Johnny Ramone performing live in New York in 1978, wielding his Mosrite guitar and delivering his buzzsaw rhythm style

Johnny Ramone performing live in New York in 1978, wielding his Mosrite guitar and delivering his buzzsaw rhythm style

The progenitor of punk-rock guitar and a significant influence on riff-driven modern metal, Johnny Ramone is a true anti-hero of the instrument. John Cummings, his real name, rose to prominence using an affordable Mosrite guitar, hammering out rapid-fire, down-stroked barre chords in a raw, minimalist style that became known as “buzzsaw.” A pure rhythm engine, Ramone almost never played solos, yet his playing possessed the relentless momentum of a runaway subway train. In an era where “heavy” was often equated with “slow,” the primal, metronomic drive of his riffs on “Blitzkrieg Bop” and “Judy Is a Punk,” and the energetic pop-punk grind of “Rockaway Beach,” demonstrated that speed could be amplified without sacrificing power. Surprisingly, his own guitar hero was Jimmy Page. “Johnny was the first guitarist I witnessed playing with genuine rage,” Henry Rollins attested. “And I thought, ‘Damn. That’s awesome.’” —W.H.

Key Tracks: “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Judy Is a Punk,” “Rockaway Beach”

Jonny Greenwood and Ed O’Brien

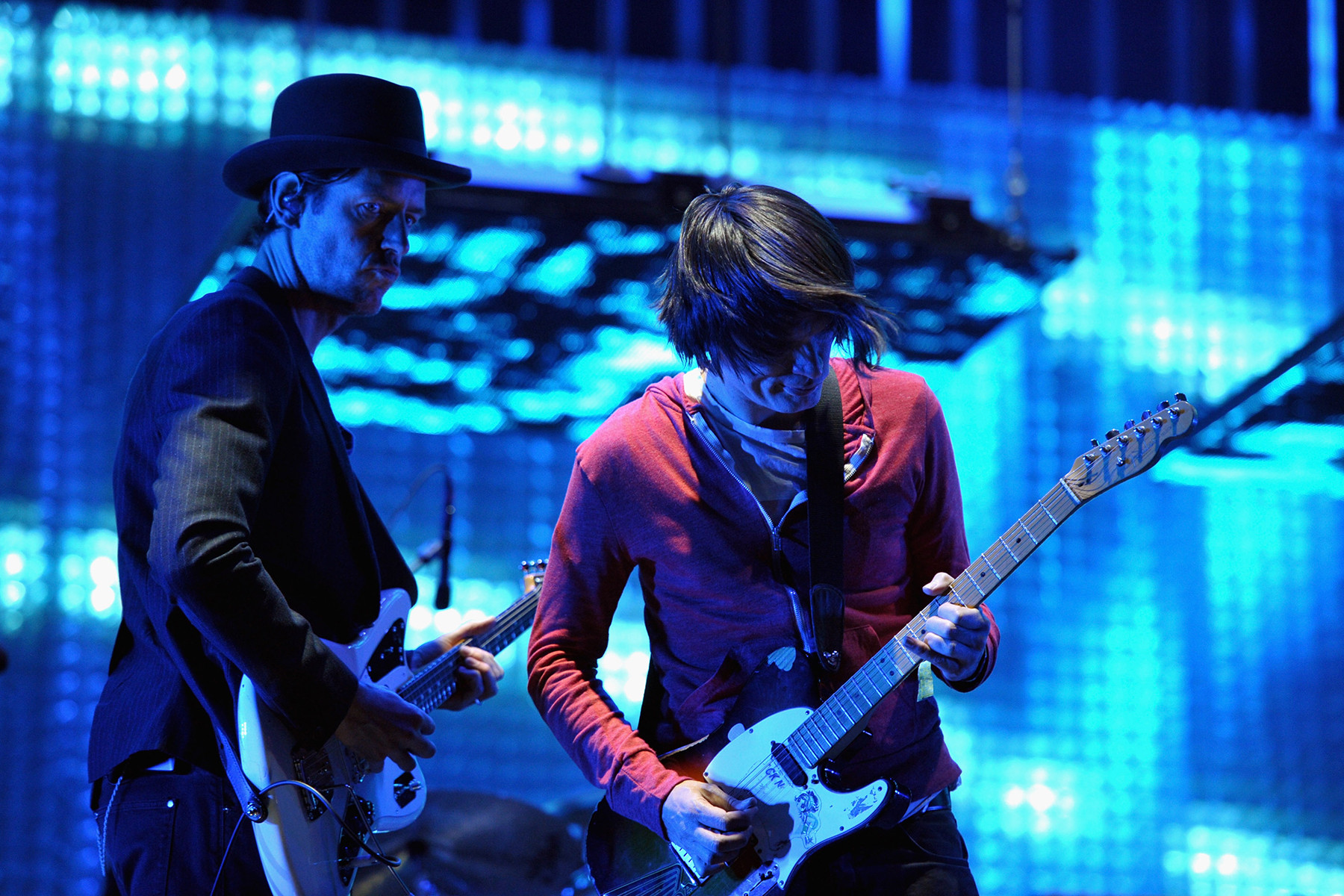

Jonny Greenwood and Ed O'Brien of Radiohead performing, showcasing their collaborative guitar work and textural soundscapes

Jonny Greenwood and Ed O'Brien of Radiohead performing, showcasing their collaborative guitar work and textural soundscapes

From the chunka-chunka outburst preceding the “Creep” chorus to the piercing high-frequency squeal in the “Just” solo, Jonny Greenwood showcased early on his penchant for unconventional guitar sounds. His aggressive playing in Radiohead’s early days led him to wear a wrist brace, but his musical curiosity quickly evolved. “Guitar isn’t really paramount to me,” he surprisingly told Guitar magazine in 1997, the same year Radiohead released “Paranoid Android.” Despite his emergence as a respected neo-classical composer, Greenwood consistently incorporates at least one mind-bending guitar moment per album. Alongside him stands Ed O’Brien, arguably one of rock’s most underrated guitarists. In any Radiohead performance, O’Brien subtly layers textures that enrich each song, providing a grounding presence with his positive and adaptable demeanor. While his standout solos might be less prominent, Radiohead without his contributions is unimaginable. —S.V.L.

Key Tracks: “Creep,” “Paranoid Android,” “I Might Be Wrong”

Vernon Reid

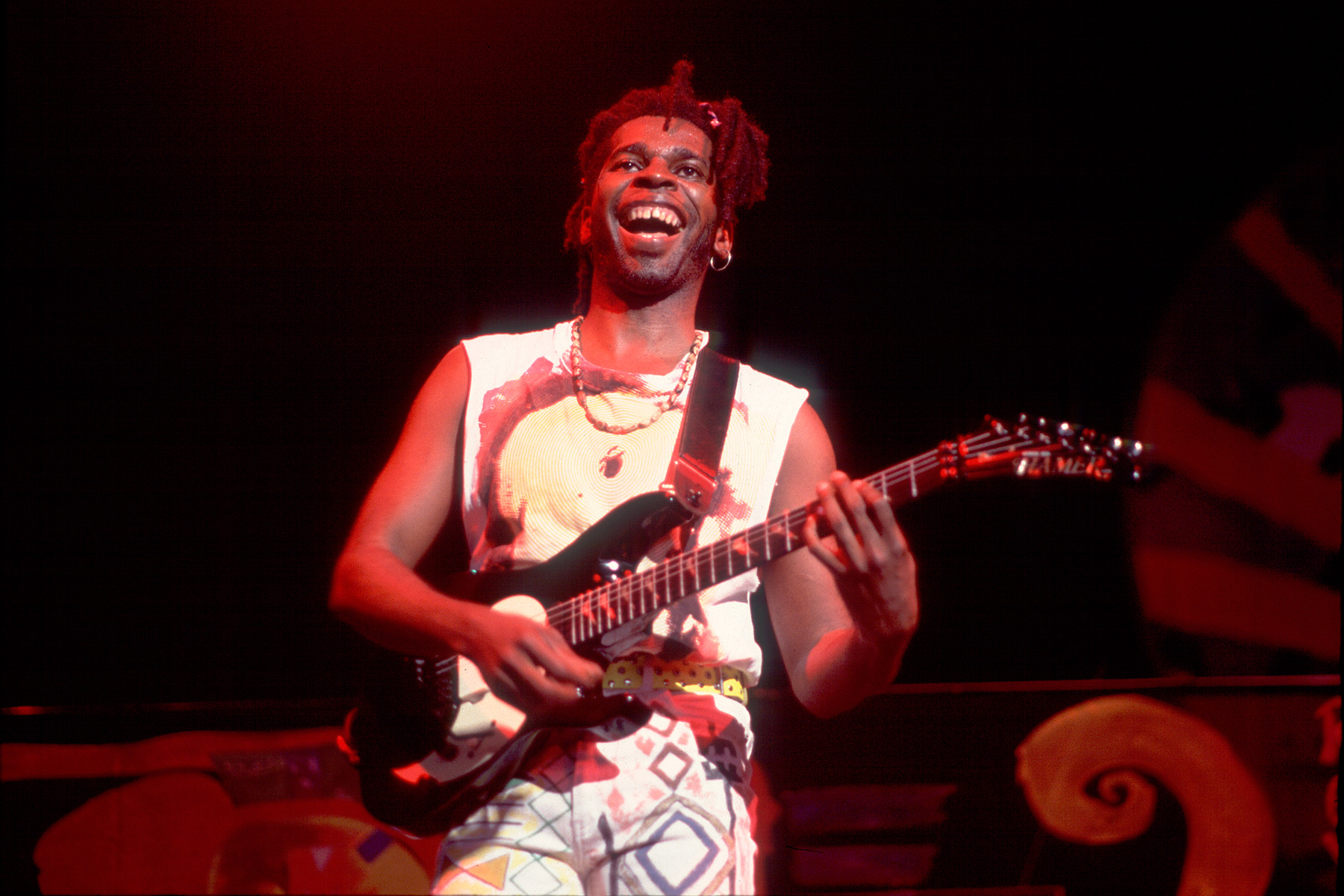

Vernon Reid of Living Colour performing in 1991, demonstrating his fusion of rock, funk, and jazz influences

Vernon Reid of Living Colour performing in 1991, demonstrating his fusion of rock, funk, and jazz influences

In the Eighties, Living Colour served as a crucial reminder that Black musicians were at the forefront of hard rock, a particularly vital message as the band achieved MTV stardom. Vernon Reid, Living Colour’s lead guitarist, demonstrated that a guitarist shaped by jazz, fusion, and funk could seamlessly integrate these influences into searing hard rock. Reid initially gained recognition in the early Eighties playing with avant-garde drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson’s band. His powerful riffing on Living Colour’s “Cult of Personality” represents just one facet of his versatility, which includes the speed-metal frenzy of “Times Up” and the virtuosic shredding on tracks like “Funny Vibe.” His diverse talent has led to collaborations with artists ranging from Mick Jagger to John Zorn. As evidenced on Living Colour’s recent album, 2017’s Shade, Reid continues to command a formidable arsenal of effects and sonic textures. —D.B.

Key Tracks: “Cult of Personality,” “Pride,” “Funny Vibe”

Bo Diddley

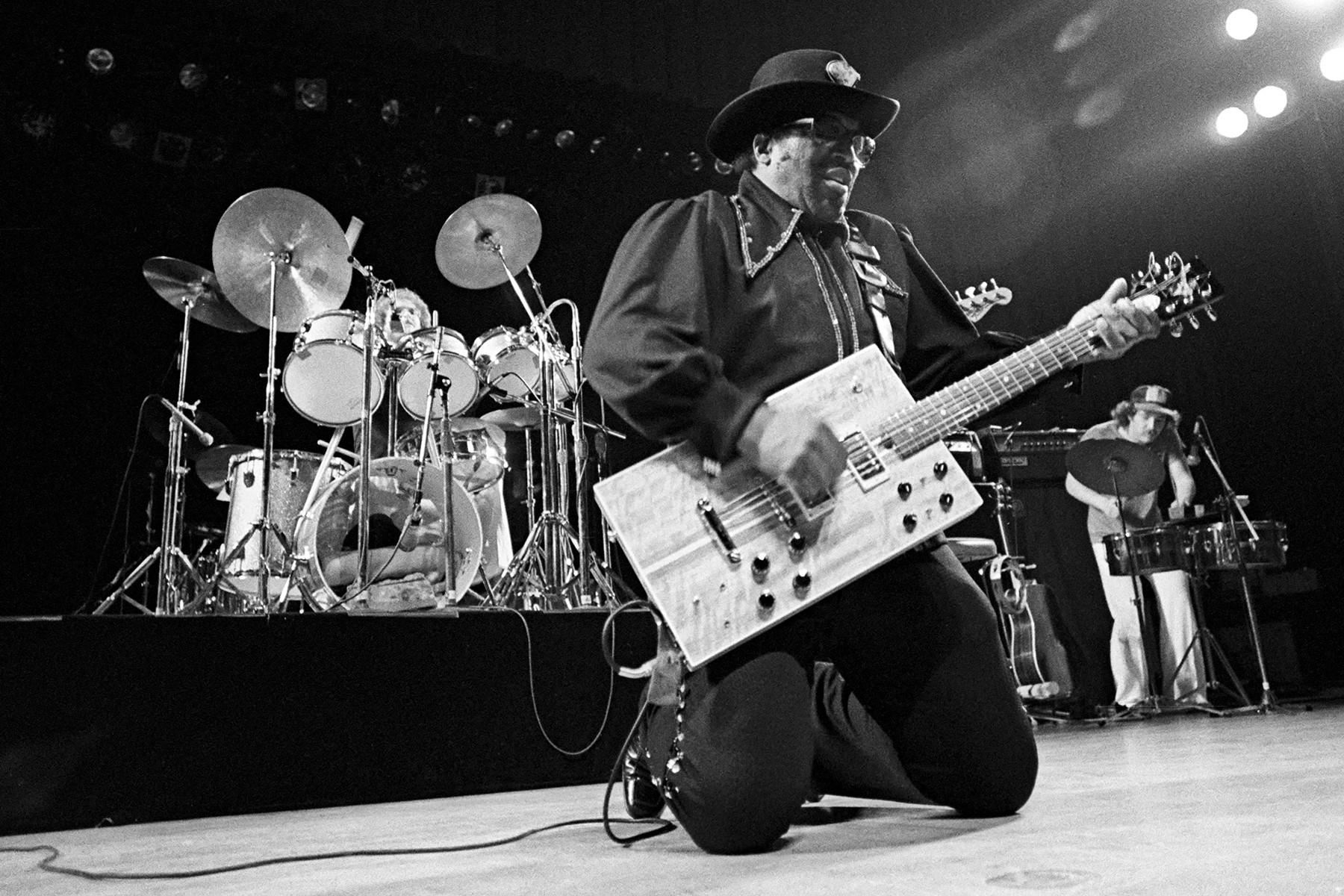

Bo Diddley performing with his signature rectangular guitar, pioneering his iconic beat and stage presence

Bo Diddley performing with his signature rectangular guitar, pioneering his iconic beat and stage presence

“It’s the mother of riffs,” declared guitarist Johnny Marr, referring to the “Bo Diddley beat,” pioneered by Chicago guitarist Ellas Otha Bates, known as Bo Diddley. Driven by his tremolo-laden guitar, songs like “Mona” and “Bo Diddley” unleashed a supercharged rendition of a West African rhythm passed down through generations. Diddley’s riff was subsequently embraced by artists from Buddy Holly to the Rolling Stones (who covered “Mona” in 1964), and later by garage rock and punk musicians, drawn to its raw simplicity. “Anyone who picked up a guitar could grasp it,” notes Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys. “If you had rhythm, you could play Bo Diddley.” “His style was outrageous,” Keith Richards observed; it suggested “that the music we loved didn’t solely originate from Mississippi. It had roots elsewhere.” —R.T.

Key Tracks: “Bo Diddley,” “Road Runner,” “Who Do You Love?”

John Fahey

John Fahey in a portrait, showcasing his fingerpicking style and his blend of folk and avant-garde elements

John Fahey in a portrait, showcasing his fingerpicking style and his blend of folk and avant-garde elements

John Fahey, who passed away in 2001 at 61, was a singular figure in American folk guitar, a brilliant fingerpicker who infused traditional blues structures with the sophisticated harmonies of modern classical music, all tempered with a playful, whimsical spirit. “His music speaks of boundless freedom,” remarked ex-Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas. Fahey recorded classic albums like 1965’s The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death and 1968’s The Voice of the Turtle for his own Takoma label. He was also an accomplished musicologist and scholar. In the Nineties, Fahey transitioned to a stark minimalism on electric guitar, becoming an unexpected post-punk icon. “To receive validation from John Fahey,” Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth noted, “was truly significant for our scene.” —W.H.

Key Tracks:“Poor Boy,” “The Yellow Princess”

Chet Atkins

Chet Atkins playing guitar in RCA Recording Studios, Nashville, 1960, demonstrating his thumb-and-finger picking style

Chet Atkins playing guitar in RCA Recording Studios, Nashville, 1960, demonstrating his thumb-and-finger picking style

As a record executive and producer in the Sixties, Chet Atkins pioneered the commercially successful “Nashville sound,” revitalizing country music. As a guitarist, he was even more innovative, mastering country, jazz, and classical styles and perfecting the art of playing chords and melody simultaneously through his distinctive thumb-and-three-finger picking technique. “Much of it was trial and error,” Atkins explained to Rolling Stone in 1976. “I simply had a guitar in my hands for 16 hours a day, constantly experimenting.” Atkins could be understated and relaxed, evident in iconic recordings like Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” and early hits by the Everly Brothers. However, his instrumental solo albums are a treasure trove of guitar techniques, blending harmonics, arpeggios, and pure notes with a remarkably clear tone. “I believe he influenced every guitarist who picked up the instrument,” Duane Eddy stated. —R.T.

Key Tracks: “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Wake Up Little Susie”

Angus Young and Malcolm Young

Angus and Malcolm Young of AC/DC performing in Boston, 1978, exemplifying their high-energy stage presence and powerful riffs

Angus and Malcolm Young of AC/DC performing in Boston, 1978, exemplifying their high-energy stage presence and powerful riffs

“Thunderstruck,” AC/DC’s 1990 anthem, sounds like the intersection of Mozart and John Lee Hooker. Angus Young delivers the electrifying classical ostinato, while his brother, Malcolm, lays down earth-shaking blues riffs, providing the bedrock for AC/DC’s explosive energy. This dynamic pairing of Angus’ flamboyant showmanship and Malcolm’s unwavering reliability propelled the band to global fame, complementing the raw vocals of Bon Scott and Brian Johnson. For every hard-hitting “Highway to Hell” or “Back in Black” riff anchored by Malcolm, Angus, the diminutive schoolboy persona, unleashed high-voltage solos that cemented his status as a guitar hero. Their combined power, evident in tracks like “Whole Lotta Rosie,” “If You Want Blood (You’ve Got It),” and “For Those About to Rock,” creates an unparalleled sonic force. —K.G.

Key Tracks: “Whole Lotta Rosie,” “Back in Black,” “Highway to Hell”

Pete Townshend

Pete Townshend of The Who smashing his guitar on stage, a symbol of his energetic performances and power chord innovation

Pete Townshend of The Who smashing his guitar on stage, a symbol of his energetic performances and power chord innovation

Pete Townshend didn’t invent power chords—guitar blasts reduced to the root and fifth notes—but he played a pivotal role in shaping modern guitar heroism by demonstrating their immense sonic potential. A prime example is the opening flourish of “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” a wall of A and E notes played across all six strings. Townshend was among the first to explore the musical possibilities of amplifier feedback, and his emphasis on riffs and songwriting over conventional solos (though his lead playing is often underrated) made him a Woodstock-era guitarist revered by punks. Townshend’s playing extended beyond sheer force, showcasing sophisticated drone notes and chord inversions in “Substitute” and “Pinball Wizard.” The Who’s live performances were always more intense than their studio recordings, and their Live at Leeds-era concerts foreshadowed the sonic landscapes of Zeppelin, heavy metal, punk, and the future of guitar music. —B.H.

Key Tracks: “My Generation,” “I Can See for Miles,” “Summertime Blues”

Elizabeth Cotten

Elizabeth Cotten playing guitar, showcasing her unique upside-down left-handed style and fingerpicking technique

Elizabeth Cotten playing guitar, showcasing her unique upside-down left-handed style and fingerpicking technique

Elizabeth Cotten’s distinctive guitar style and sound emerged from her self-taught approach. The North Carolinian, who once worked for the Seeger family, was left-handed but learned on a right-handed guitar, simply flipping it over without restringing. This unconventional approach allowed her to develop a rhythmic technique that alternated fingerpicked bass notes and thumbed melodies, exemplified in her famous composition “Freight Train.” “It’s simply my comfort, my way of doing things, not conforming to others,” she told the San Diego Reader in 1981. “I couldn’t do it the conventional way. I tried, and I could barely strum.” Rediscovered during the 1960s folk revival after decades of obscurity, Cotten was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an Early Influence in 2022. –J.F.

Key Tracks: “Freight Train,” “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad”

Eric Clapton

Eric Clapton playing a Fender Stratocaster in Rome, 1986, showcasing his melodic blues-rock guitar style and expressive solos

Eric Clapton playing a Fender Stratocaster in Rome, 1986, showcasing his melodic blues-rock guitar style and expressive solos

From his early days in the British blues-rock scene of the 1960s, Eric Clapton possessed a rare melodic gift, making his guitar solos as memorable as the songs themselves. A dedicated student of the blues, from Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters to Albert King and Otis Rush, he even recorded an album of pre-electric blues repertoire with Wynton Marsalis. However, his most enduring recordings often stemmed from personal tragedy, from “Layla,” inspired by his love for Patti Boyd, his best friend’s wife, to “Tears in Heaven,” a lament for his young son. While the “Clapton is God” era may be past, his profound influence on guitarists remains undiminished, with his playing still deeply revered. —J.D.C.

Key Tracks: “Bell Bottom Blues,” “Crossroads,” “White Room”

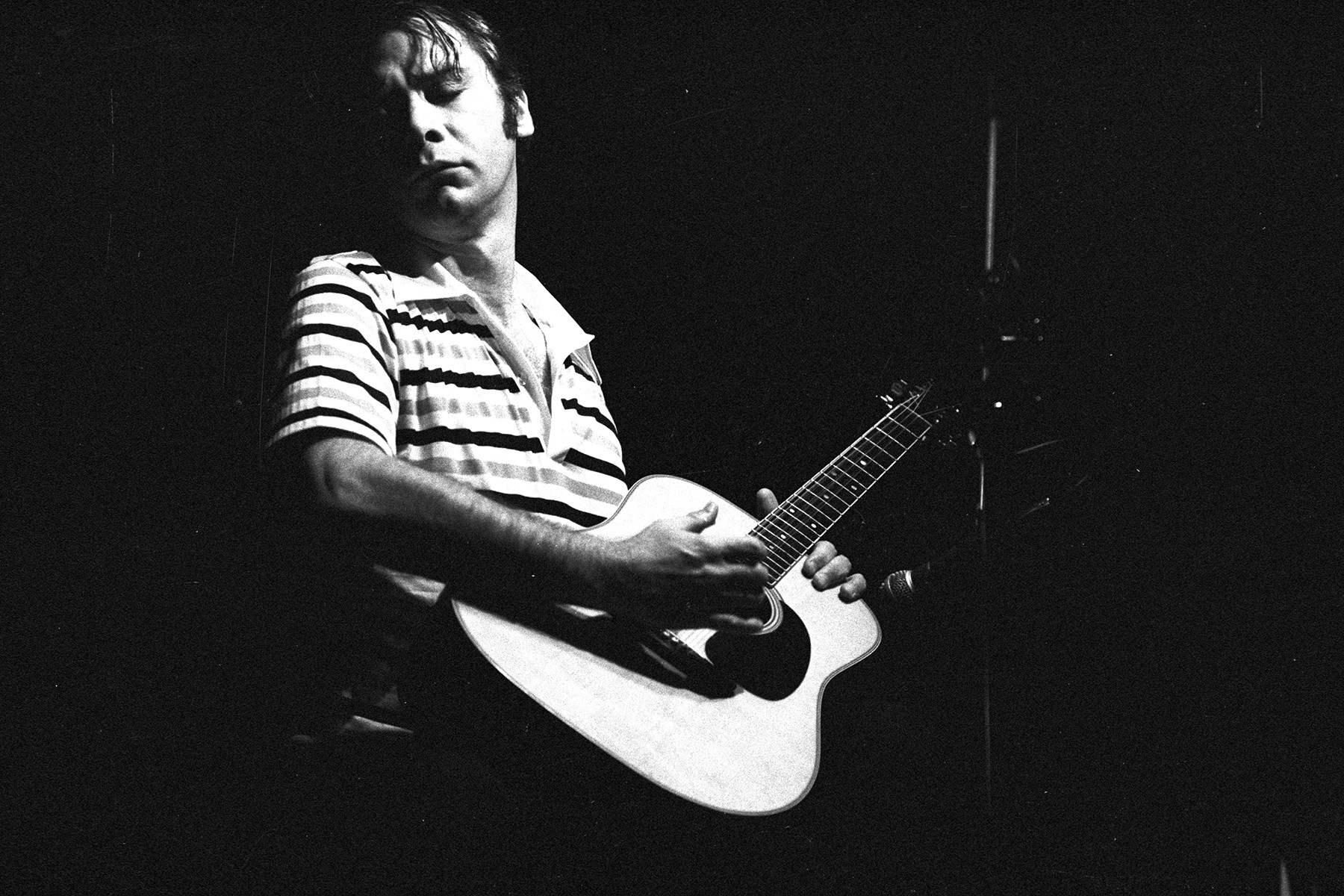

Jerry Garcia

Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead performing in London, 1972, showcasing his improvisational and psychedelic guitar style

Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead performing in London, 1972, showcasing his improvisational and psychedelic guitar style

Jerry Garcia, a devotee of folk and bluegrass who started playing guitar at 15, blended these roots with a lifelong passion for Chuck Berry, fueling his psychedelic explorations with the Grateful Dead. As Carlos Santana observed, “He played blues but infused it with bluegrass and Ravi Shankar. He incorporated country and Spanish elements.” Garcia transformed each Grateful Dead concert into a unique sonic journey, never repeating a lick, making his live psychedelic jams endlessly rewarding to revisit. “I perceive notes as objects with perspective,” he once told Rolling Stone. “They have a front and back, an attack and release. For me, it’s intensely visual. If time allowed, I would illustrate all my solos.” August 27, 1972, stands as a legendary date in guitar history, when Garcia’s playing soared in Veneta, Oregon. Though he passed away in 1995, his guitar legacy continues to shine brightly. —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Dark Star” (2/27/69), “Bird Song” (8/27/72), “Morning Dew” (5/8/77)

Brian May

Brian May of Queen performing in Oakland, 1978, playing his homemade Red Special guitar and showcasing his layered harmonies

Brian May of Queen performing in Oakland, 1978, playing his homemade Red Special guitar and showcasing his layered harmonies

Possibly the only guitarist with an astrophysics degree, Queen’s lead guitarist (and prolific songwriter) Brian May is an intellectually curious musician, constantly seeking new sonic effects. An early ambition was “to be the first to record proper three-part [guitar] harmonies”—like the orchestrated squeals in his “Killer Queen” solo. Brian May meticulously layered dozens of guitar parts onto individual tracks, constructing majestic walls of sound. Fittingly, his instrument itself originated from his imagination: his main guitar, the Red Special, a homemade marvel crafted with his father in the early Sixties from materials including fireplace wood. He is known to play it with a sixpence coin instead of a pick. This unique instrument has produced everything from the intricate, trebly solo in “Bohemian Rhapsody” to the proto-metal riffing of “Stone Cold Crazy.” “I can mimic the sound of almost any guitarist,” Steve Vai admitted, “but Brian May is beyond my reach. He operates on a higher plane.” —D.W.

Key Tracks: “Keep Yourself Alive,” “Brighton Rock”

Jack White

Jack White performing at Governors Ball 2014, showcasing his raw blues-garage style and energetic stage presence

Jack White performing at Governors Ball 2014, showcasing his raw blues-garage style and energetic stage presence

When the White Stripes gained traction with albums like 2000’s De Stijl, mainstream guitar rock was dominated by the overly processed sounds of nu-metal and the lethargic pace of second-wave grunge. This landscape shifted dramatically with the raw, garage-blues energy of “Fell in Love With a Girl,” catapulting the Stripes to stardom. Jack White gifted us the most recognizable rock riff of the 21st century with the heavy, low-end stomp of “Seven Nation Army.” However, he has consistently avoided resting on past achievements, evolving into a wonderfully eccentric sonic explorer—from the stoner funk and folk elements of his 2012 solo album Blunderbuss to the almost cartoonishly over-the-top, fuzz-laden drones of 2022’s Fear of the Dawn. For White, each time he picks up a guitar, it’s a new challenge. “When I play a solo, it’s an act of aggression—a fight, a struggle,” White told Rolling Stone in 2014. “Virtuosity is irrelevant to me. If you interrupted me mid-solo, I couldn’t tell you ‘That’s an F-sharp, that’s a C.’” —J.D.

Key Tracks: “Seven Nation Army,” “Ball and Biscuit”

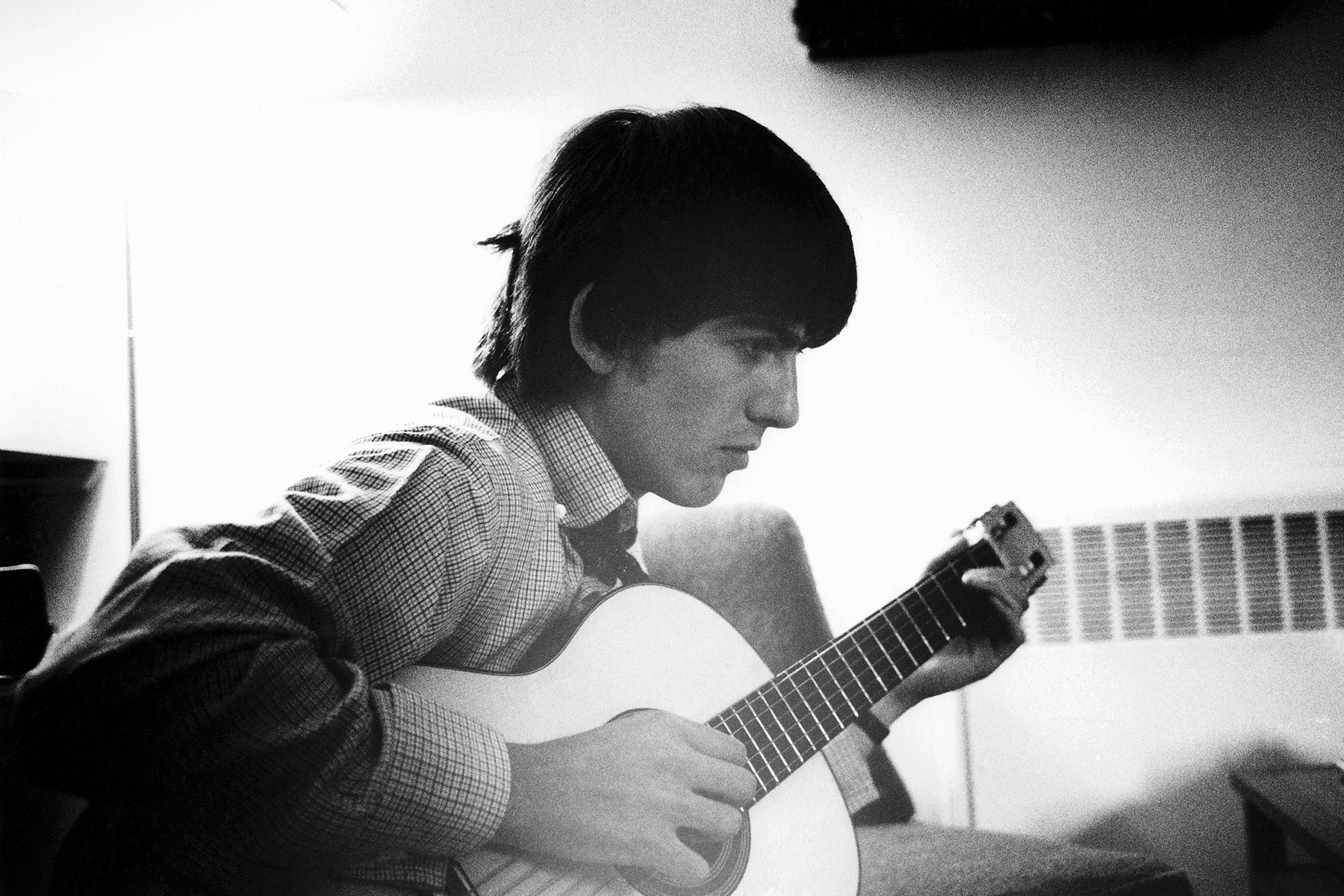

George Harrison

George Harrison of The Beatles playing acoustic guitar at Twickenham Film Studios, showcasing his innovative guitar work within pop music

George Harrison of The Beatles playing acoustic guitar at Twickenham Film Studios, showcasing his innovative guitar work within pop music

With the Beatles, George Harrison redefined the guitar’s role, constantly innovating and expanding its sonic possibilities with each album. He didn’t just become a lead guitarist in a rock band; he defined the guitar’s central place in pop music. Early on in Liverpool, he honed his skills, mastering chords and surpassing his bandmates. He drew inspiration from rockabilly heroes like Carl Perkins, evident in his energetic Cavern Club solo on “I Saw Her Standing There.” But he continued to experiment with Indian-inspired drones on Rubber Soul, psychedelia on Revolver, and elegance on Abbey Road, always playing with purpose. “Everyone else has explored all the other avenues,” Harrison once said. “I just play what’s left.” His most profound playing emerged after the Beatles, with his ethereal slide guitar work on All Things Must Pass and Living in the Material World. As his friend Tom Petty noted, “It truly sounded like a voice, a uniquely identifiable voice emanating from him.” —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Something,” “Let It Be,” “Give Me Love”

Neil Young

Neil Young in a portrait from circa 1970, showcasing his raw and emotional guitar style across acoustic and electric genres

Neil Young in a portrait from circa 1970, showcasing his raw and emotional guitar style across acoustic and electric genres

Long before his successful solo career, Neil Young refined his guitar skills in the Squires, the Mynah Birds, and Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. By the time Harvest arrived, he was equally proficient on electric and acoustic guitar, seamlessly transitioning between gentle folk songs like “The Needle and the Damage Done” and raw, proto-grunge tracks like “Down by the River” in a single performance. “If I were to teach a master class to young guitarists, the first thing I would play is the opening minute of Neil Young’s original ‘Down by the River’ solo,” Trey Anastasio stated. Some guitar purists have dismissed his work as “primitive,” noting that some of his most famous solos are built on single repeated notes. However, they miss the core of his artistry. “No one cares about your scale knowledge,” Young said in 1992. “Technique is irrelevant. It’s about expressing emotions through music, that’s what truly matters.” —A.G.

Key Tracks: “Cowgirl in the Sand,” “Powderfinger,” “Rockin’ in the Free World”

Eddie Hazel

Eddie Hazel of Parliament in 1977, showcasing his psychedelic funk guitar style and his legendary "Maggot Brain" solo

Eddie Hazel of Parliament in 1977, showcasing his psychedelic funk guitar style and his legendary "Maggot Brain" solo

Legend has it that “Maggot Brain,” Eddie Hazel’s ten-minute guitar solo that instantly elevated him to guitar legend status, was conceived during an acid trip. Funkadelic leader George Clinton instructed him to imagine his mother’s death, followed by the news she was alive. “I knew instantly he grasped my meaning,” Clinton wrote in his memoir. “I could visualize the guitar notes extending like a silver web. Upon hearing the solo playback, I knew it transcended mere virtuosity, becoming an unprecedented emotional expression in pop music.” Hazel’s broader work with P-Funk and his solo endeavors blended groove-driven power with psychedelic flights. However, “Maggot Brain” remains his most influential piece, inspiring guitarists like Nels Cline, J. Mascis, Warren Haynes, and Mike McCready, who have all performed it live, channeling Hazel’s profoundly gifted spirit. —W.H.

Key Tracks: “Maggot Brain,” “Funky Dollar Bill”

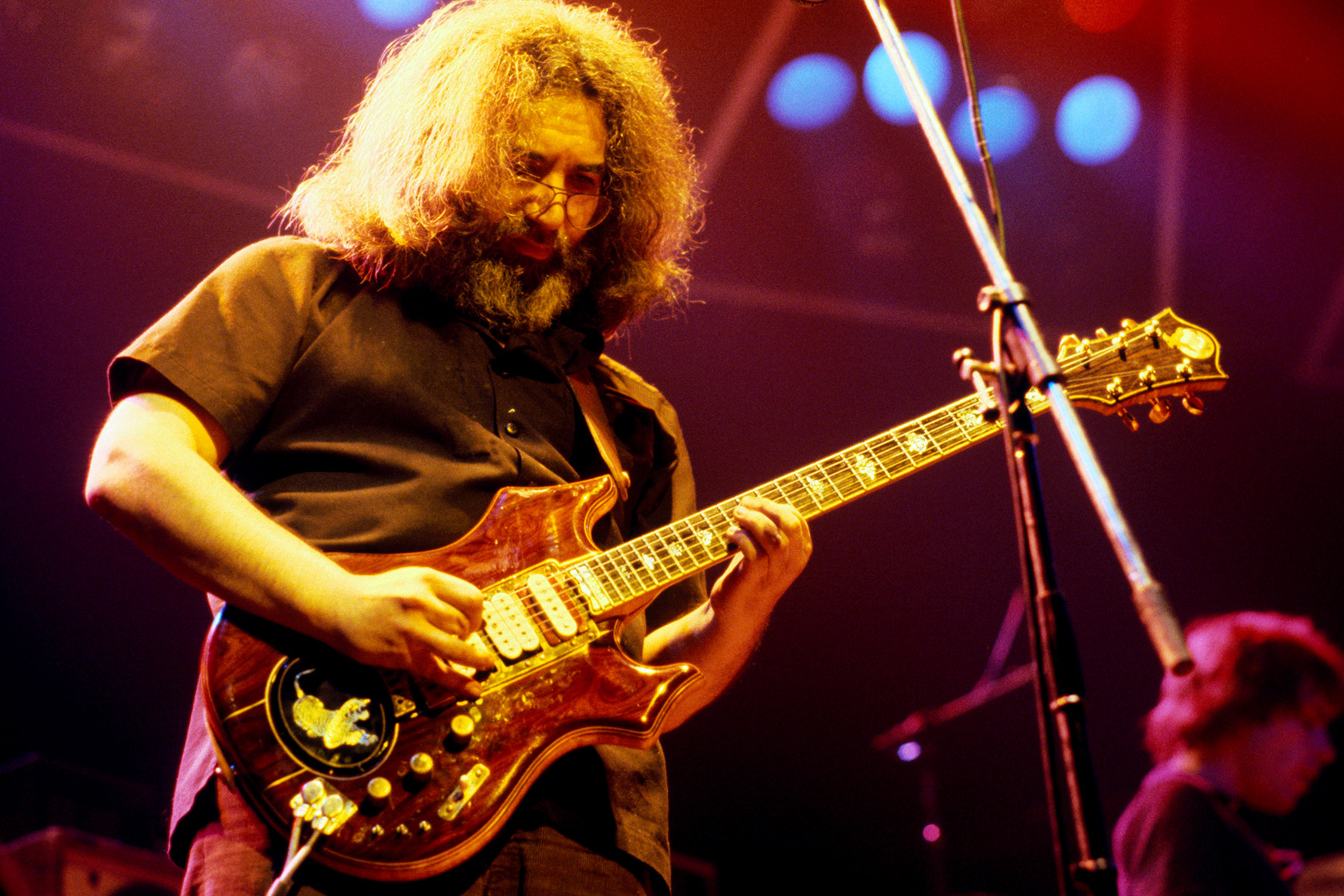

David Gilmour

David Gilmour of Pink Floyd playing at Hakone Aphrodite, 1971, showcasing his melodic and atmospheric guitar style

David Gilmour of Pink Floyd playing at Hakone Aphrodite, 1971, showcasing his melodic and atmospheric guitar style

As a producer and songwriter, Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour favors ethereal, dreamlike textures. However, when he picks up his black Stratocaster for a solo, a different intensity emerges. “I aimed for a bright, powerful lead guitar tone that would essentially rip your face off,” he explains. He was a fiery, blues-based soloist in a band that rarely played blues—his expansive, melodic solos served as a sonic wake-up call within Pink Floyd’s soundscapes. Gilmour also excelled at avant-garde improvisation, evident in Floyd’s Live at Pompeii performances, and could be an unexpectedly funky rhythm guitarist, from the slinky riff of “Have a Cigar” to the Chic-inspired flourishes on “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” His pioneering use of echo and effects, initially inspired by Syd Barrett, culminated in his precise delay application on “Run Like Hell,” directly anticipating The Edge’s signature sound.

Key Tracks: “Comfortably Numb,” “Shine on You Crazy Diamond”

Buddy Guy

Buddy Guy performing live in Nice, France, 1978, showcasing his flamboyant blues guitar style and energetic stage presence

Buddy Guy performing live in Nice, France, 1978, showcasing his flamboyant blues guitar style and energetic stage presence

Buddy Guy became accustomed to his guitar style being labeled as noise—from family members in rural Louisiana who chased him out for the racket, to Chess Records executives who, he says, “wouldn’t allow me to fully express myself” on sessions with Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Little Walter. However, as a new generation of rockers discovered the blues, Guy’s fretwork became a major influence on figures from Jimi Hendrix to Jimmy Page. Guy’s flamboyant playing—wide bends, prominent distortion, frenetic licks—on classics like “Stone Crazy” and “First Time I Met the Blues,” and his collaborations with harmonica master Junior Wells, elevated the standard for guitar intensity. His showmanship, including mid-solo walks through the audience, remains electrifying at 87. “He was to me what Elvis was to others,” Eric Clapton stated at Guy’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2005. “My path was set, and he was my guide.” —A.L.

Key Tracks: “Stone Crazy,” “First Time I Met the Blues”

St. Vincent

St. Vincent performing in Charlotte, NC, 2018, showcasing her innovative and textural guitar approach within her complex music

St. Vincent performing in Charlotte, NC, 2018, showcasing her innovative and textural guitar approach within her complex music

Annie Clark, known as St. Vincent, crafts intricate and atmospheric music that isn’t inherently guitar-centric, yet deeply marked by her innovative approach to the instrument. Though educated at Berklee College of Music and influenced by dexterous players like Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew, and Marc Ribot, the Grammy-winning artist layers her recordings with arresting guitar tones, colors, voicings, harmonies, and effects. She prioritizes composition and emotional impact over technical displays. “I don’t approach guitar as an ego-driven pursuit—like, ‘I’m going to play faster than anyone else,’” Clark explained to Premier Guitar in 2011. “I’m not interested in that athletic aspect. That’s the distinction between being an athlete and an artist, though the ideal is when those elements converge—creating something musically compelling and emotionally resonant, finding that perfect balance.” —D.E.

Key Tracks: “Rattlesnake,” “Cruel,” “Masseduction”

John Frusciante

John Frusciante of Red Hot Chili Peppers performing in 2007, showcasing his eclectic guitar style and his role in shaping the band's sound

John Frusciante of Red Hot Chili Peppers performing in 2007, showcasing his eclectic guitar style and his role in shaping the band's sound

The Red Hot Chili Peppers have defied easy categorization, largely thanks to Frusciante, son of a Juilliard pianist. Replacing the band’s original guitarist, Hillel Slovak, was a challenge, but Frusciante, now in his third stint with the Chili Peppers, played a key role in pushing them beyond the white-funk label into their own unique musical territory. Always prioritizing the song, Frusciante broadened the Chili Peppers’ sonic palette: from the heavy riffing in their cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground,” to the delicate strumming in “Under the Bridge” and “Scar Tissue,” the metallic funk of “Give It Away,” the moody textures of “Breaking the Girl,” and the explosive Hendrix-esque solo in “Dani California.” This eclectic approach gave albums like Californication and Blood Sugar Sex Magik remarkable depth, establishing Frusciante as a vital and influential guitarist of the alt-rock era. —D.B.

Key Tracks: “Dani California,” “Under the Bridge”

James Burton

James Burton performing with Emmylou Harris Hot Band in Amsterdam, 1975, showcasing his "chicken pickin'" style and country guitar mastery

James Burton performing with Emmylou Harris Hot Band in Amsterdam, 1975, showcasing his "chicken pickin'" style and country guitar mastery

James Burton’s signature “chicken pickin’” style—bright, crisp, and concise—is a defining sound in country music and a significant influence on rock guitar. Burton began his career at 14, writing “Susie Q” for Dale Hawkins, and became a teen idol joining Ricky Nelson’s band in 1957. With Nelson, Burton perfected his technique: using a fingerpick and flat pick, and replacing the highest four strings on his Telecaster with banjo strings, creating a snappy, percussive tone. “I never bought a Ricky Nelson record,” Keith Richards admitted. “I bought a James Burton record.” In the late Sixties and Seventies, he led Elvis Presley’s TCB Band and became a sought-after guitarist for country-influenced records by Joni Mitchell and Gram Parsons. “He was enigmatic: ‘Who is this guy on all these records I love?’” Joe Walsh wondered. “His technique was paramount.” —A.L.

Key Tracks: “Hello Mary Lou,””Susie Q,” “Believe What You Say”

James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett

James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett of Metallica performing in Tokyo, 1986, showcasing their dual guitar attack and metal innovation

James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett of Metallica performing in Tokyo, 1986, showcasing their dual guitar attack and metal innovation

Metallica stormed onto the scene as speed metal pioneers, with singer-rhythm guitarist James Hetfield delivering breakneck riffs, like Black Sabbath at double speed, and lead guitarist Kirk Hammett unleashing notes with abandon. Hetfield and Hammett’s predecessor, Dave Mustaine (a guitar hero in his own right with Megadeth), developed techniques to minimize finger movement for maximum speed, redefining metal on tracks like “Phantom Lord” and “Jump in the Fire.” However, by Metallica’s second album, when Hammett, a former student of Joe Satriani, began adding soulful melodies to songs like “Fade to Black” and “The Call of Ktulu,” the band achieved a unique sound. This duality—Hetfield’s raw power and Hammett’s emotive, wah-driven expression—defined their greatest successes: “Enter Sandman,” “One,” “Master of Puppets”—songs that capture the band’s blend of aggression and vulnerability. —K.G.

Key Tracks: “One,” “Fade to Black,” “Sad But True”

Albert King

Albert King in a portrait from circa 1970, showcasing his powerful string bending and unique upside-down guitar style

Albert King in a portrait from circa 1970, showcasing his powerful string bending and unique upside-down guitar style

When Rolling Stone asked Albert King in 1968 about his guitar influences, he replied, “Nobody. Everything I do is wrong.” A pioneer of electric blues, King (left-handed) played a right-handed 1959 Gibson Flying V upside down, with bass strings facing downwards. He used an unknown tuning, striking notes with his thumb. The imposing King could bend notes further and more powerfully than most, profoundly influencing a generation. Eric Clapton borrowed the “Strange Brew” solo from King, and Duane Allman transformed King’s “As the Years Go Passing By” melody into the main riff of “Layla.” Jimi Hendrix was awestruck opening for his hero at the Fillmore in 1967. “I taught [Hendrix] a blues lesson,” King claimed. “I could easily play his songs, but he couldn’t play mine.”

Key Tracks: “Born Under a Bad Sign,” “As the Years Go Passing By”

Randy Rhoads

Randy Rhoads performing in Chicago, 1982, showcasing his virtuosic and architectural metal guitar style

Randy Rhoads performing in Chicago, 1982, showcasing his virtuosic and architectural metal guitar style

Randy Rhoads’ career was tragically short, ending with his death in a plane crash in 1982 at 25. Yet, his precise, architectural, and lightning-fast solos on Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” and “Mr. Crowley” set the template for metal guitar soloing for years to come. “I practiced eight hours a day because of him,” Tom Morello stated, calling Rhoads “the greatest hard-rock/heavy-metal guitarist of all time.” Rhoads co-founded Quiet Riot as a teenager, joining Osbourne’s Blizzard of Ozz in 1979 after teaching guitar. Legend claims Rhoads continued taking guitar lessons on tour with Ozzy. By his final album, Osbourne’s Diary of a Madman, Rhoads explored classical music and jazz, “reaching deep into himself as a guitarist,” Nikki Sixx of Mötley Crüe observed, “that was truly the next level.” —D.W.

Key Tracks: “Crazy Train,” “Mr. Crowley,” “Diary of a Madman”

Stevie Ray Vaughan

Stevie Ray Vaughan in a portrait, showcasing his powerful blues-rock guitar style and his influence on generations of guitarists

Stevie Ray Vaughan in a portrait, showcasing his powerful blues-rock guitar style and his influence on generations of guitarists

In the early Eighties, MTV was ascendant, and blues guitar was far from mainstream. But Stevie Ray Vaughan from Texas commanded attention. He absorbed the styles of blues guitar greats, Jimi Hendrix, jazz, and rockabilly. His massive tone, effortless virtuosity, and impeccable swing made a blues shuffle like “Pride and Joy” hit as hard as metal. Vaughan earned peer recognition from B.B. King and Eric Clapton. Despite his 1990 death in a helicopter crash, he inspires guitarists across generations, from Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready to John Mayer and Gary Clark Jr. “Stevie was a reason I wanted a Stratocaster—his tone, which I’ve never replicated, was massive and bold and bright,” Clark said. “Listening to his records and videos, you sense his complete commitment. His passion is overwhelming.” —W.H.

Key Tracks: “Love Struck Baby,” “Cold Shot”

Freddy King

In a 1985 interview, Eric Clapton cited Freddy King’s 1961 B-side “I Love the Woman” as “the first time I heard that electric lead-guitar style, with bent notes… [it] set me on my path.” Clapton shared his admiration for King with fellow British guitar heroes Peter Green, Jeff Beck, and Mick Taylor, all deeply influenced by King’s sharp tone and concise melodic hooks on singles like “The Stumble,” “I’m Tore Down,” and “Someday, After Awhile.” Nicknamed “The Texas Cannonball” for his imposing physique and fiery shows, King had a unique guitar attack. “Steel on steel is unforgettable,” Derek Trucks notes, referring to King’s banjo picks. “But it needs the right hands. The way he used it—you were going to hear that guitar.” Trucks still hears King’s influence in Clapton. “Playing with Eric,” Trucks said recently, “sometimes his solos would evoke that Freddy vibe.” —D.F.

Key Tracks: “Hide Away,” “The Stumble”

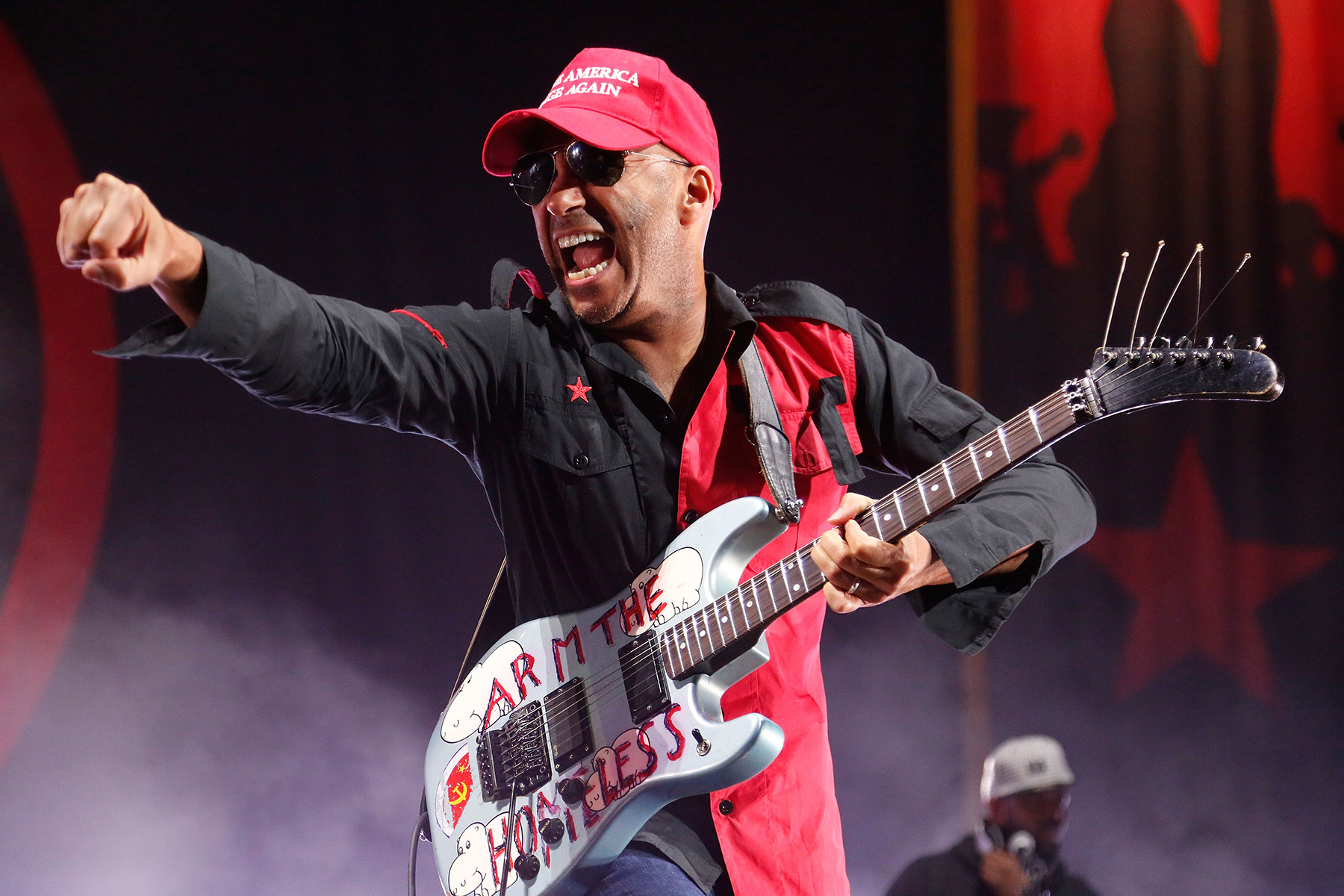

Tom Morello

Tom Morello of Prophets of Rage performing, showcasing his innovative and effects-driven guitar style

Tom Morello of Prophets of Rage performing, showcasing his innovative and effects-driven guitar style

With rare exceptions like Hendrix, rock guitars for decades largely sounded like…rock guitars. Then came Rage Against the Machine and Tom Morello. Just as Zack de la Rocha injected politics into the mix, Morello revolutionized guitar sounds. The turntable scratching on “Bulls on Parade” from Evil Empire? The video-game sounds on “Killing in the Name,” or the dive-bomber attack on “Fistful of Steel,” both from Rage’s debut? All Morello, using guitars, pedals, and imagination. Morello’s blend of effects and thunderous chords recalled heroes like the Stooges’ Ron Asheton (on Rage’s “Sleep Now in the Fire”), but Morello added even more moxie. Since Rage’s studio disbandment, Morello’s work with Nightwatchman and Street Sweeper Social Club is more restrained, but his challenge to guitar clichés remains impactful. —D.B.

Key Tracks: “Guerrilla Radio,” “Killing in the Name”

Mother Maybelle Carter

Maybelle Carter performing at the A.P. Carter Memorial Festival, 1977, showcasing her signature "Carter Scratch" guitar style

Maybelle Carter performing at the A.P. Carter Memorial Festival, 1977, showcasing her signature "Carter Scratch" guitar style

Maybelle Carter didn’t invent her signature guitar style—”the Carter Scratch”—in isolation. She credited roots pioneer Lesley Riddle with teaching her the fingerpicking style. But she popularized it globally through Carter Family singles like “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” “Wildwood Flower,” and “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow.” Carter’s playing, starting at 13, transformed guitar from rhythm strumming to melody, rhythm, and bass simultaneously. Singer-songwriter Courtney Marie Andrews called her “perhaps the most emulated guitarist ever.” “When I started, I had no one to play with,” she once explained, “so I developed this style.” —J.B.

Key Tracks: “Wildwood Flower,” “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow”

Robert Johnson

Robert Johnson in a retouched portrait from circa 1935, showcasing his legendary status and his profound influence on blues and rock guitar

Robert Johnson in a retouched portrait from circa 1935, showcasing his legendary status and his profound influence on blues and rock guitar

Largely unknown for decades after his 1938 death, Robert Johnson’s 29 recordings from 1936-37—including “Cross Road Blues,” “Love in Vain,” and “Traveling Riverside Blues”—became sacred texts for rock guitarists from Clapton to Dylan. They were captivated by his ability to make one guitar sound like an ensemble—picking, slide, and rhythm parts in dialogue, riffs emerging and receding. Cream, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and the White Stripes covered his songs, as did countless blues-inspired artists. In Chronicles, Bob Dylan recalls hearing Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers after its release: “The first note made my hair stand up. The guitar sounds could almost break a window.” —D.W.

Key Tracks: “Ramblin’ on My Mind,” “Traveling Riverside Blues”

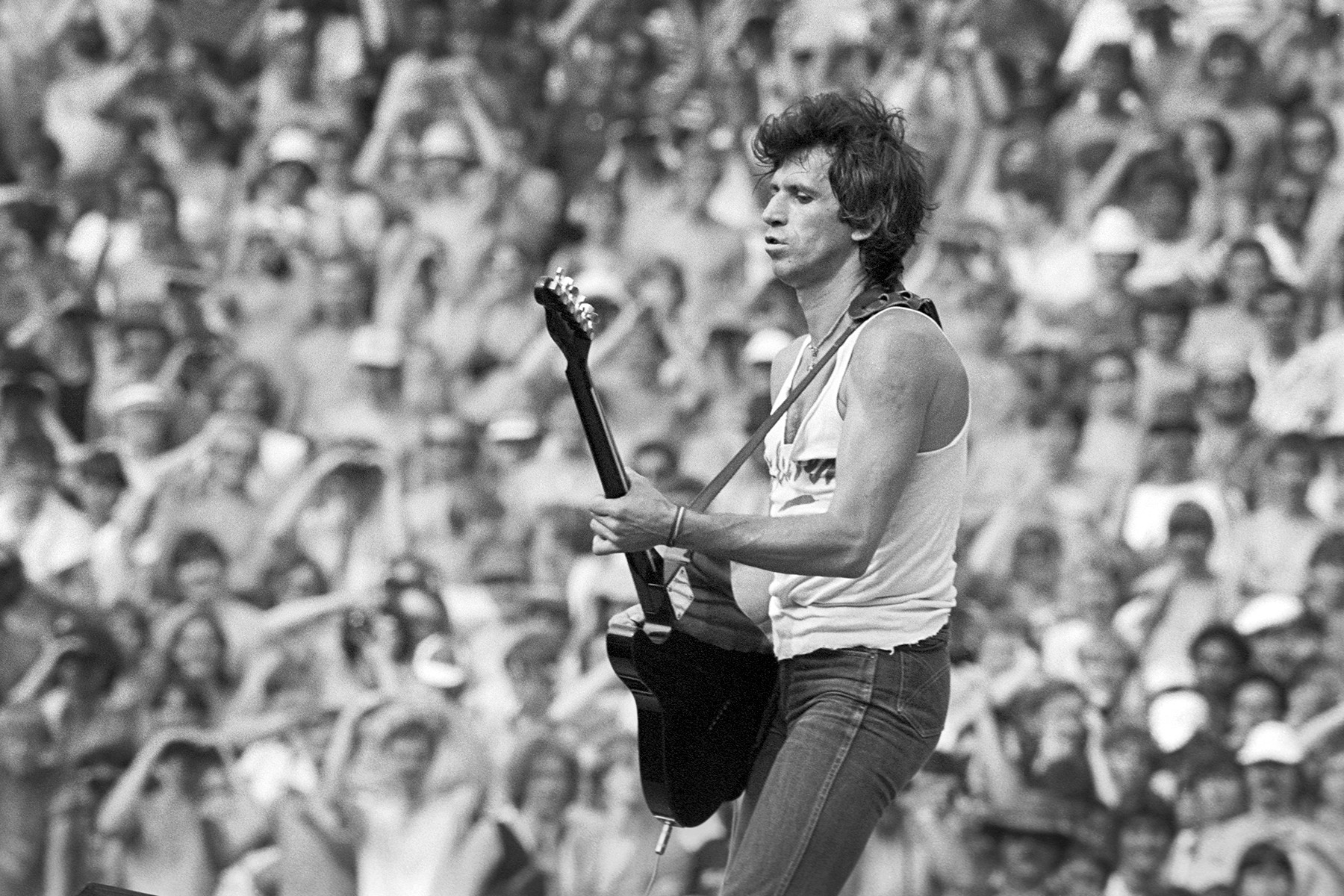

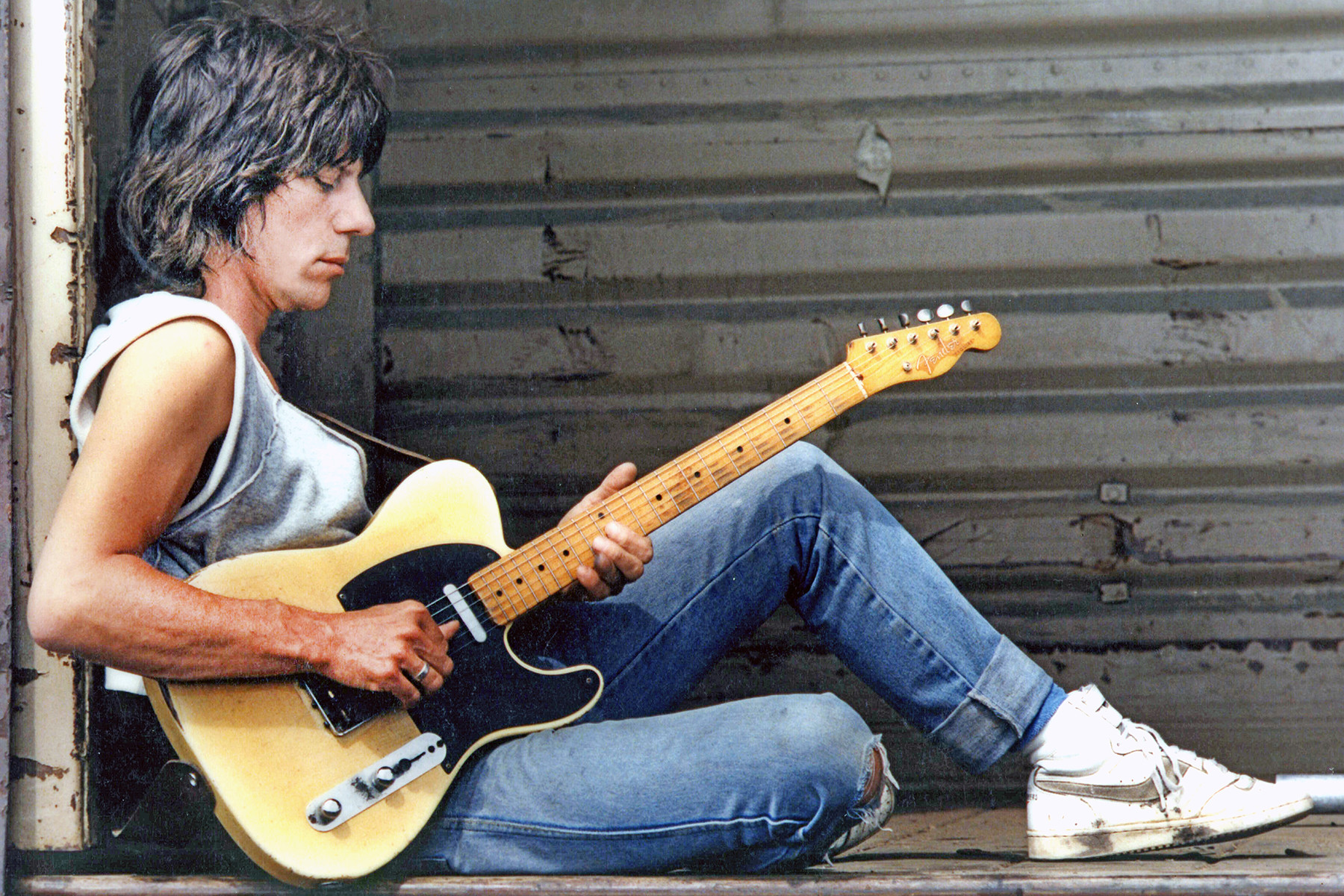

Keith Richards

Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones performing in Rotterdam, 1982, showcasing his riff-based guitar style and effortless cool

Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones performing in Rotterdam, 1982, showcasing his riff-based guitar style and effortless cool

Keith Richards has always made guitar playing look effortless. The power of his riffs—”(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “Start Me Up,” “Brown Sugar”—lies in their raw simplicity, symmetry, and effortless swing. In the Sixties, his solid playing supported Brian Jones’s diverse instrumentation; Richards provided a swinging base for Jones’s slide and marimba on “Time Is on My Side,” “Paint It, Black,” and “Under My Thumb.” In the Seventies, with Mick Taylor, Richards created lush grooves for “Tumbling Dice,” “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” “Wild Horses.” Acoustically, he’s adept at blues (“Love in Vain”) and ballads (“Angie”). With Ron Wood, they form a musical yin and yang, weaving guitar parts between riffs and solos. “[A great riff] appears at your fingertips, coming from the instrument,” he told Rolling Stone in 2020. “Totally unthought, unstructured, no rules. One minute it’s not there, the next, it is.” —K.G.

Key Tracks: “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “Gimme Shelter”

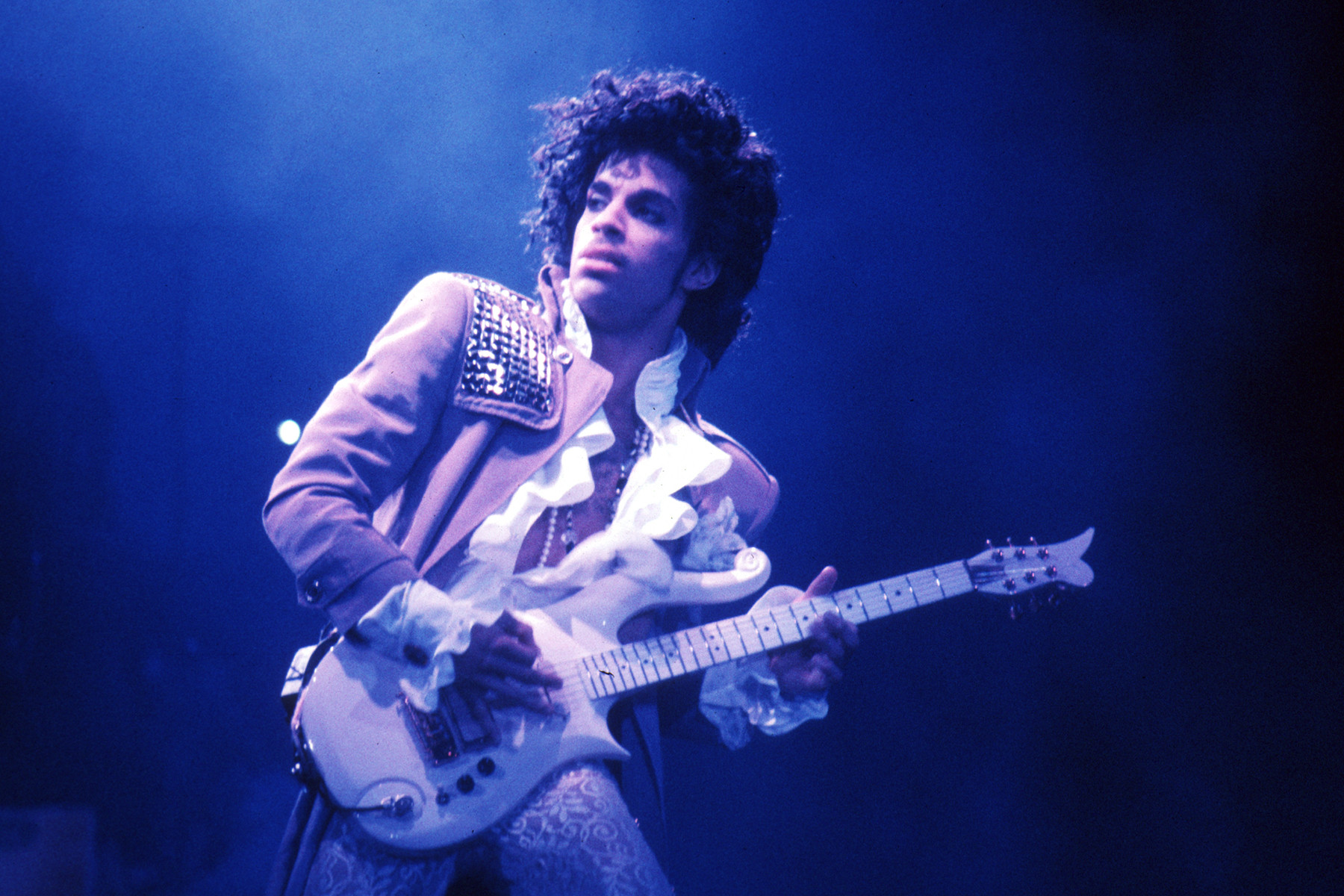

Prince

Prince performing in Inglewood, 1985, showcasing his virtuosic guitar playing and his flamboyant stage persona

Prince performing in Inglewood, 1985, showcasing his virtuosic guitar playing and his flamboyant stage persona

Prince delivered arguably the greatest power-ballad guitar solo in history (“Purple Rain”). He could funk like Jimmy Nolen and Nile Rodgers, or scream like Eddie Van Halen. Like Bo Diddley, he reimagined guitar design—the yellow “cloud guitar” and the “symbol guitar.” While often compared to Hendrix, Prince saw it differently: “Only because he’s Black. That’s the sole commonality,” he told Rolling Stone. “Listen closely, and you’ll hear more Santana than Hendrix. Hendrix leaned blues; Santana, prettier.” He also noted a perk of guitar god status: “Playing electric guitar your whole life does something. All that electricity through my body kept my hair.” —W.H.

Key Tracks: “Purple Rain,” “When Doves Cry”

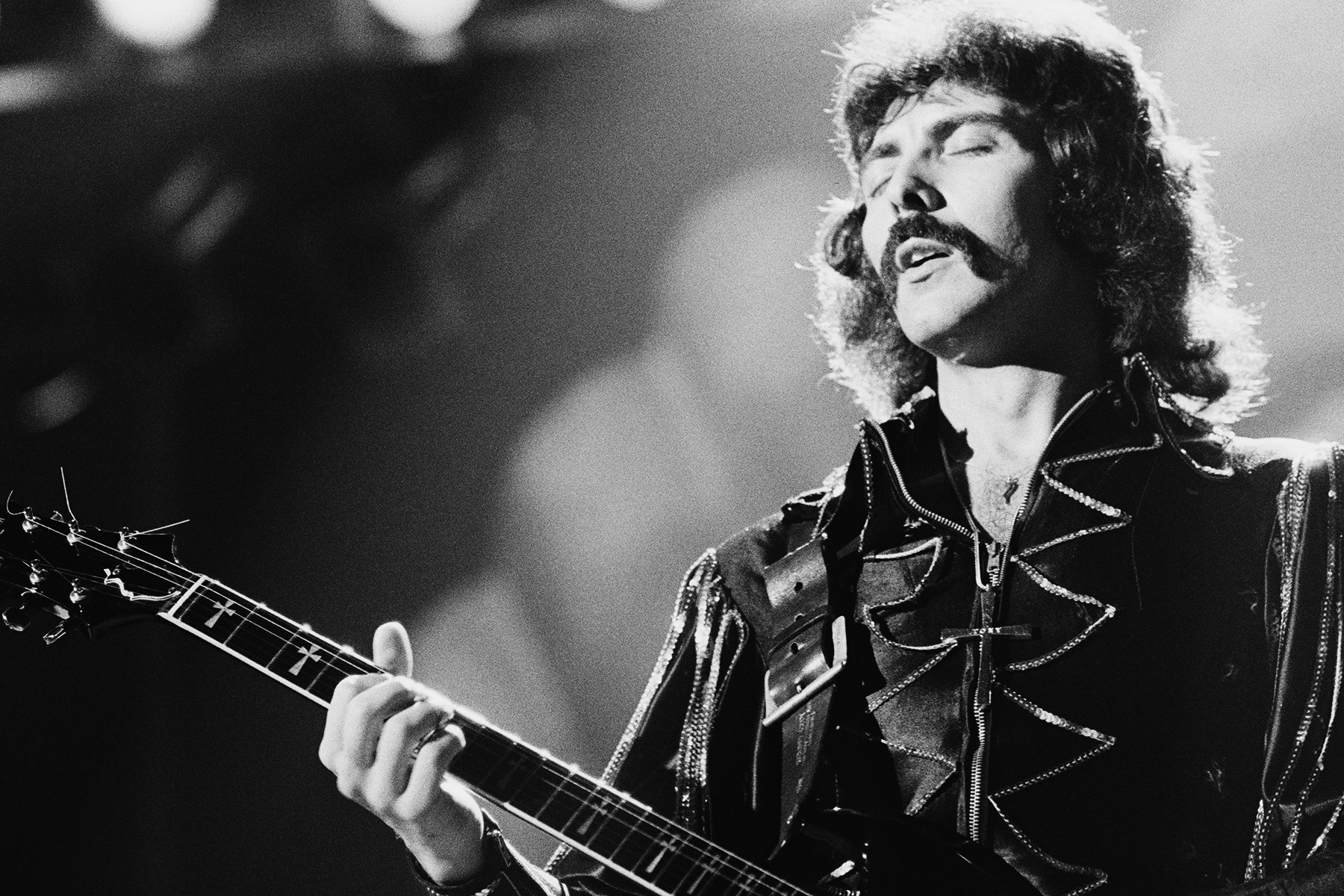

Tony Iommi

Tony Iommi of Black Sabbath performing in London, 1976, showcasing his doomy metal guitar style and his signature sound

Tony Iommi of Black Sabbath performing in London, 1976, showcasing his doomy metal guitar style and his signature sound

A pillar of heavy metal guitar, Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommi developed his signature doomy style after an industrial accident severed fingertips on his fretting hand. Plastic finger caps allowed him to play, but forced lighter strings and harder fretting. Combined with distorted Laney amps boosted by a modified Dallas Rangemaster, this necessity created a uniquely dark and menacing sound. Tuning down guitars for easier bends, Iommi established the template for countless metal guitarists. “Back then, you made your sound,” Iommi told Guitar World in 2020. “No gadgets to instantly create sounds; you built your tone. That felt great, believing in something you created yourself.” —D.E.

Key Tracks: “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,” “Symptom of the Universe”

Jimmy Nolen

Jimmy Nolen performing with James Brown, pioneering funk guitar rhythm and creating the signature James Brown sound

Jimmy Nolen performing with James Brown, pioneering funk guitar rhythm and creating the signature James Brown sound

Years before joining James Brown, Jimmy Nolen developed a way to compensate for weak drummers: “I tried to play rhythm like a drum as much as possible,” he said. “To keep the drummer straight.” Joining Brown in 1965, Nolen’s bright rhythm and Brown’s rhythmic fire ignited. While real life was less romantic—Nolen died in 1983, requesting Brown ease up on his successors—the results are undeniable. Starting with 1965’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”—the intro is Nolen’s—and continuing through classics like “Let Yourself Go,” “Cold Sweat,” and “Funky Drummer,” Nolen defined funk and R&B guitar: choppy rhythm, precise leads, both central and peripheral to the action. —M.M.

Key Tracks: James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” and “Cold Sweat”

Carlos Santana

Carlos Santana performing in 1975, showcasing his fusion of Latin, blues, and jazz guitar styles

Carlos Santana performing in 1975, showcasing his fusion of Latin, blues, and jazz guitar styles

Carlos Santana’s pioneering fusion of blues, jazz, and Latin music exploded at Woodstock. It was equally powerful 30 years later when Supernatural sold 15 million and won nine Grammys. Santana remained constant, conjuring melodies with roots in both the barrio and astral planes. “His music was new, but intertwined with everything else,” said Henry Garza of Los Lonely Boys. “He incorporated his culture.” Like Miles Davis and B.B. King, Santana is identifiable in a single note. He aimed to emulate jazzmen like Wes Montgomery and Grant Green, but “I always sounded like me.” No one replicates Santana’s crystalline tone, but his impact is global. Prince cited him as a bigger influence than Hendrix: “Santana played prettier.” —A.L.

Key Tracks: “Black Magic Woman,” “Oye Como Va,” “Soul Sacrifice”

Duane Allman

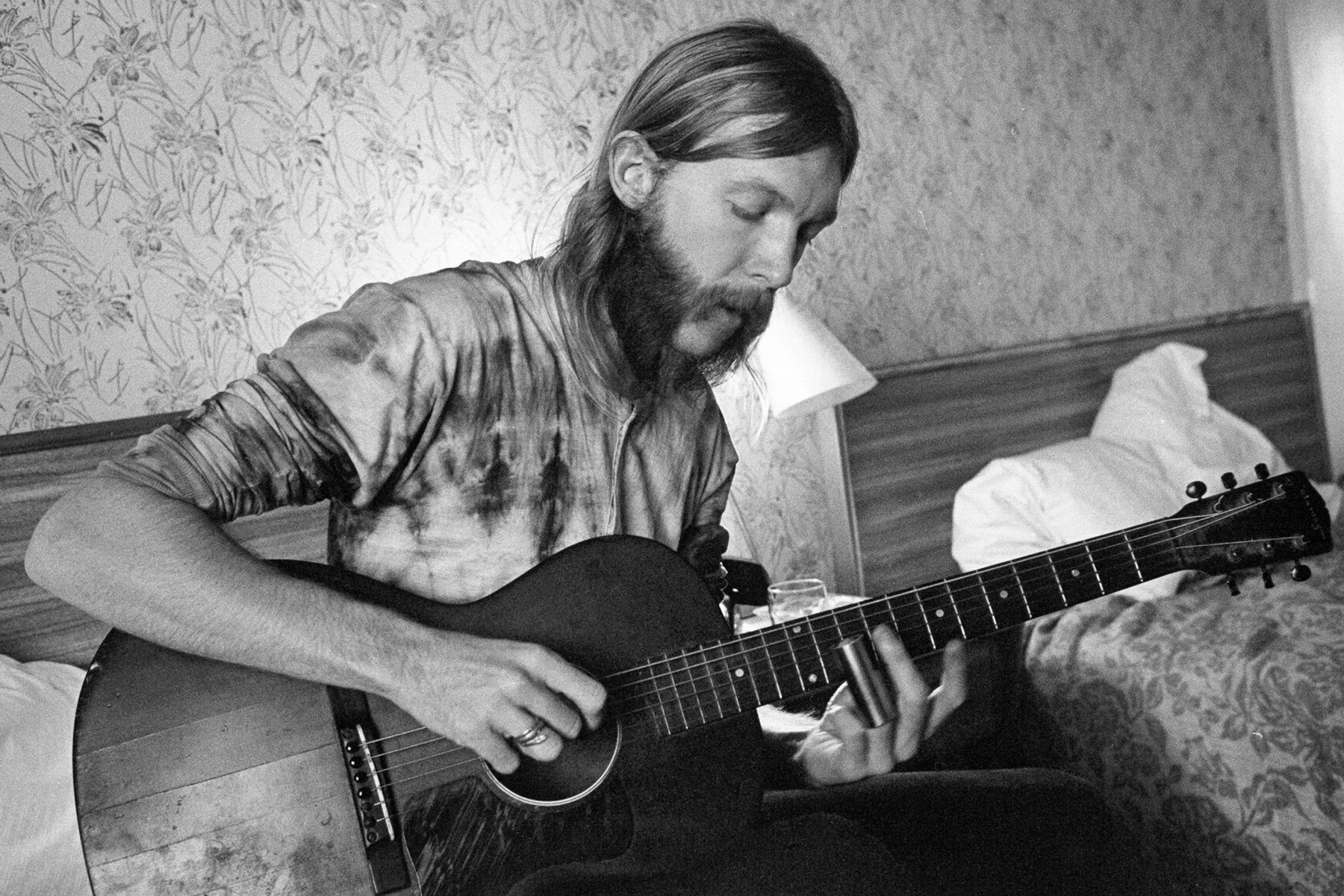

Duane Allman playing slide guitar in a hotel room, showcasing his visionary slide guitar style and his influence on Southern rock

Duane Allman playing slide guitar in a hotel room, showcasing his visionary slide guitar style and his influence on Southern rock

Duane Allman’s life was short—24 when he died in a 1971 motorcycle crash—but packed with guitar innovation. With the Allman Brothers Band, he traversed American music: modal jazz, blues, country, Southern rock. As a teen, he learned guitar playing along to Robert Johnson and Chuck Berry. He first gained recognition as a sideman, notably at Muscle Shoals with Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin. He formed the ABB in 1969 with brother Gregg. Their first jam led Duane to declare, “Anyone not wanting to be in my band will have to fight their way out.”

His defining work: At Fillmore East, improvising under the influence of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, from “Statesboro Blues” to the 19-minute “You Don’t Love Me.” He also joined Derek and the Dominos for Layla, creating history with Eric Clapton, particularly his slide shriek in the title track. His symbolic farewell was the lullaby “Little Martha.” Its notes are on his tombstone. The road took Duane too soon, but his music’s road goes on. —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Statesboro Blues,” “You Don’t Love Me,” “Whipping Post”

Joni Mitchell

Joni Mitchell performing on The Mama Cass Television Program, 1969, showcasing her unique acoustic guitar style and alternate tunings

Joni Mitchell performing on The Mama Cass Television Program, 1969, showcasing her unique acoustic guitar style and alternate tunings

Joni Mitchell has reigned as rock’s ultimate acoustic guitarist for over 50 years, using alternate tunings to create her complex guitar language. “I wanted to play guitar like an orchestra,” she told Rolling Stone in 1999. “My playing is unique, but unnoticed. Describing it as folk guitar when it’s more Duke Ellington feels silly.” Polio weakened her left hand, leading to over 50 tunings. “Top three strings were a horn section; bottom three, rhythm.”

Musicians were awestruck. “Am I a god?” she asked Rolling Stone. “A godette. Never had a guitar god.” Hejira (1976), with Jaco Pastorius, showcases her best playing. As chords became too complex for sidemen, she took over electric leads—half on Hejira, nearly all on Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Mingus. In Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder doc, she plays “Coyote” for Roger McGuinn and Bob Dylan—McGuinn stares at her hands, disbelieving the chords. “Her rich modal tunings left a big impression,” Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo said. “Joni’s playing was mysterious.” —R.S.

Key Tracks: “For the Roses,” “Coyote,” “Refuge of the Roads”

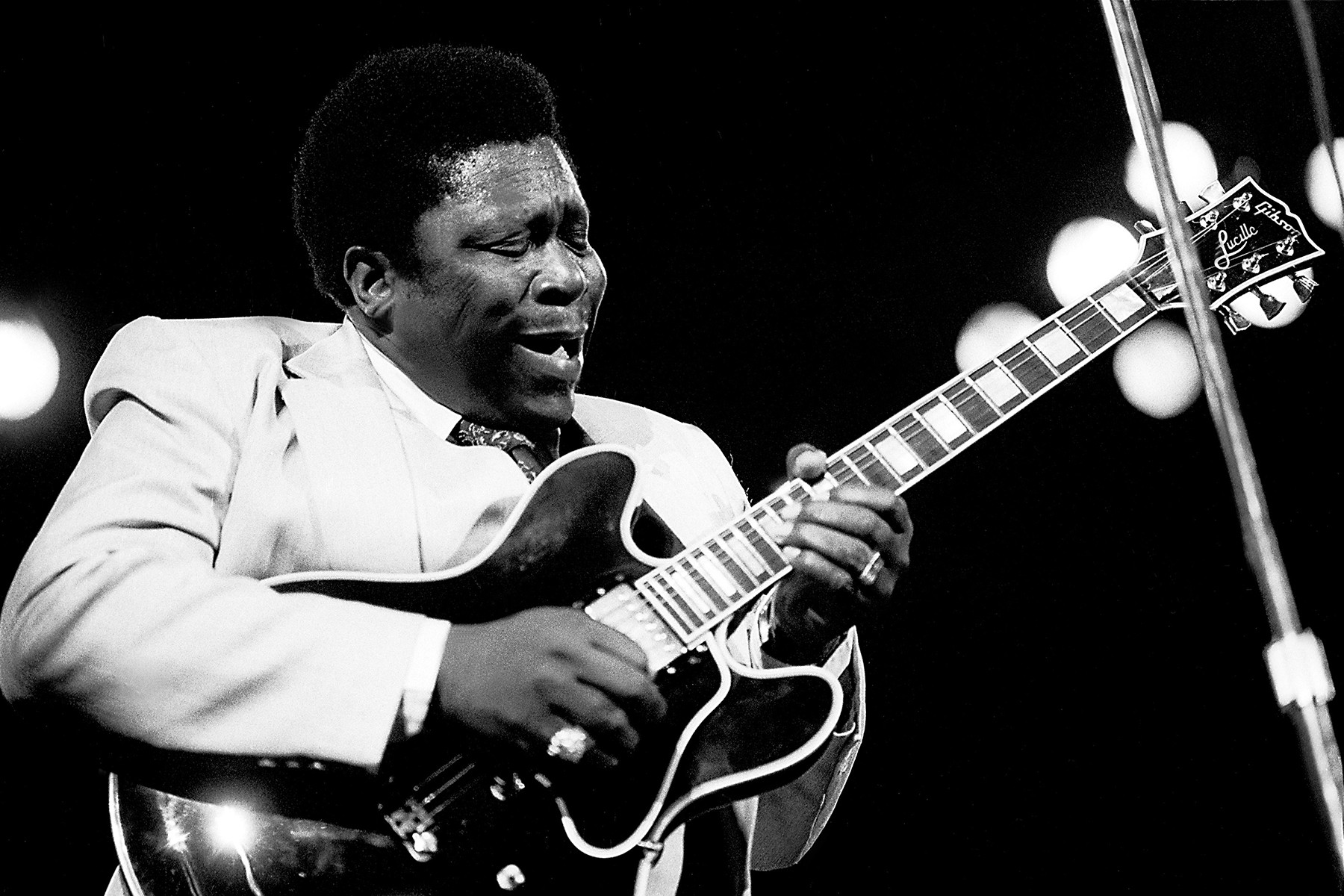

B.B. King

B.B. King performing at Rosemont Horizon, 1980, showcasing his expressive blues guitar style and his iconic "Lucille" guitar

B.B. King performing at Rosemont Horizon, 1980, showcasing his expressive blues guitar style and his iconic "Lucille" guitar

The “Ambassador of the Blues” was so beloved, it’s easy to overlook his revolutionary guitar work. Buddy Guy said, “Before B.B., everyone played guitar like acoustic.” King made his Gibson “Lucille” weep like a person. From “Three O’Clock Blues” (1951), his fluid style is evident. His string-bending and vibrato came from T-Bone Walker, but he took it further, changing guitar playing. “Every electric guitarist owes B.B.,” Guy said. “He fathered squeezing strings on electric guitar.”

King grew up on a Mississippi Delta plantation, learning country blues from cousin Bukka White. He moved to Memphis in 1948, becoming a radio DJ and developing his eclectic style with gospel and jazz. Live at the Regal (1965) remains a guitar showcase. Touring into his late eighties, he cherished Lucille. “Lucille only plays blues,” King said. “She’s real. Playing her is like hearing words, and cries.” —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Every Day I Have The Blues,” “Sweet Sixteen,” “The Thrill Is Gone”

Nile Rodgers

Nile Rodgers performing in his Let's Dance suit, showcasing his massively influential funk guitar style and his signature "chucking"

Nile Rodgers performing in his Let's Dance suit, showcasing his massively influential funk guitar style and his signature "chucking"

There’s “influential,” “massively influential,” then Nile Rodgers. Pop music’s story for 50 years is Rodgers’ guitar story. His manic funk jangle with Chic, in disco hits like “Le Freak” and “Good Times,” is pop’s heartbeat. His rapid guitar on Diana Ross’s “I’m Coming Out” (1980) remained tough radio sound almost two decades later when Biggie sampled it for “Mo Money Mo Problems.” That’s staying power.

He founded Chic with Bernard Edwards, inspired by Roxy Music. “Initially, I played heavy rock & roll,” Rodgers told Rolling Stone in 1979. “Success was being Hendrix or Page.” His dynamic Strat powers classics for Ross (“Upside Down”), Sister Sledge (“We Are Family”), Bowie (“Let’s Dance”), Duran Duran (“Notorious”), Daft Punk (“Get Lucky”). His riffs launched hip-hop—Sugarhill Gang rhymed over “Good Times” for “Rapper’s Delight.” His impact—jazzy chords and rhythms—is everywhere. He heavily influenced the Smiths; Johnny Marr called Rodgers his hero, naming his son “Nile.” A true innovator, still making guitar history. —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Le Freak,” “Good Times,” “I’m Coming Out”

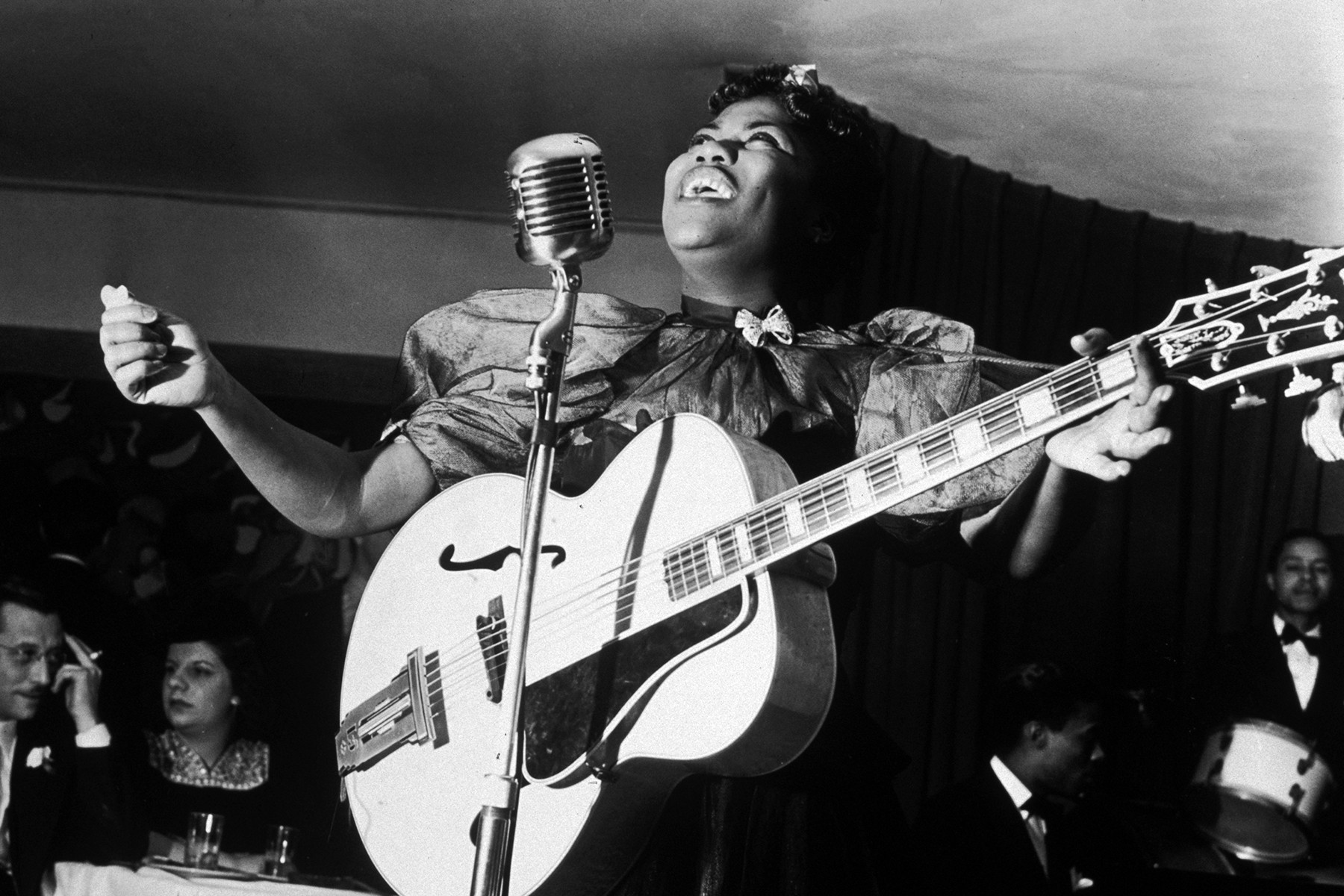

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing at Cafe Society Downtown, 1940, pioneering the concept of guitar hero and blending gospel with electric guitar

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing at Cafe Society Downtown, 1940, pioneering the concept of guitar hero and blending gospel with electric guitar

As a sexually fluid Black woman who brought gospel into the mainstream, Sister Rosetta Tharpe shattered taboos. Before rock & roll, she virtually invented the guitar hero. Bob Dylan called her a “powerful force of nature—a guitar-playing, singing evangelist.” Inspired by her mother’s mandolin, Tharpe learned guitar around kindergarten. By her Thirties recordings, she’d mastered it. Her picking and arpeggios on 1945’s “Strange Things Happening Every Day” matched its boogie-woogie and her singing. She unleashed solo rumbles in “Up Above My Head.” In 1964, Clapton, Richards, and Beck reportedly went to a Manchester train station to see Tharpe play for TV. Her “Didn’t It Rain” showed her gospel power and guitar artistry. Tharpe died in 1973, but her legacy grows. Brittany Howard inducted her into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as an early influence. —D.B.

Key Tracks: “Strange Things Happening Every Day”

Jeff Beck

Jeff Beck playing a Fender Telecaster in 1985, showcasing his innovative and vocal-like guitar style

Jeff Beck playing a Fender Telecaster in 1985, showcasing his innovative and vocal-like guitar style

Jeff Beck never sought guitar hero status. He left the Yardbirds, disbanded the Jeff Beck Group (skipping Woodstock), and let bands fade before fame. Despite rejecting fame, he needed to play guitar. His technique evolved from blues mastery with the Yardbirds and Jeff Beck Group to wah-wah driven Stratocaster sounds on “Beck’s Bolero.” A constant sound innovator, Beck explored jazz fusion in the mid-Seventies, making guitar his focus on Blow by Blow, an instrumental album featuring whammy bar flicks, grace notes, and note bends mirroring Syreeta’s voice on “‘Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers.”

He perfected interpreting the human voice on guitar: pride in “People Get Ready,” shimmering sadness in “Nadia,” sighing interpretations of “Over the Rainbow” and “Nessun Dorma.” “I never made the big time, mercifully,” Beck said in 2018. “Seeing who did, it’s rotten. Maybe I’m blessed to avoid that.” —K.G.

Key Tracks: “Beck’s Bolero,” “Freeway Jam,” “‘Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers”

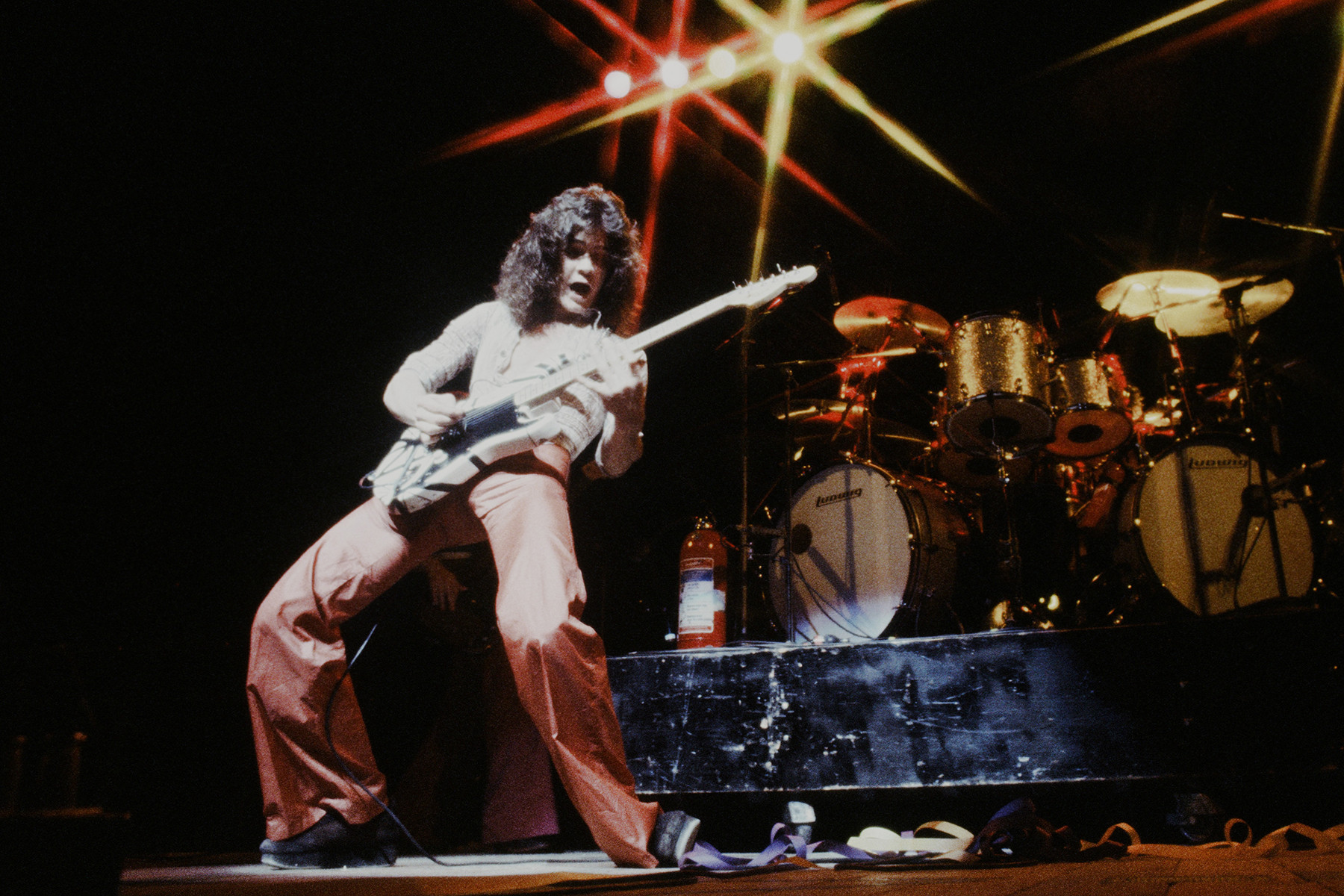

Eddie Van Halen

Eddie Van Halen performing in Tokyo, 1978, showcasing his revolutionary tapping technique and his high-energy stage presence

Eddie Van Halen performing in Tokyo, 1978, showcasing his revolutionary tapping technique and his high-energy stage presence

If “Eruption” were Eddie Van Halen’s sole release, he’d still be a guitar icon. Finger-tapped, piano-like sounds, dive bombs, trumpet-like calls—it showed guitar capabilities beyond imagination. But Van Halen’s true magic was turning tricks into singalong songs: “Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love,” “Dance the Night Away,” “Everybody Wants Some!!,” “Jump”—tunes blending technique and catchy lyrics.

Beyond anthems, solos like “Spanish Fly,” “Cathedral,” and “Little Guitars” felt compositional. He never stopped experimenting; recording an electric drill on “Poundcake.” “With Eddie Van Halen, everyone was riveted,” Tom Morello said after his death. “We knew we were in the presence of our Mozart.” Even when not playing, Van Halen innovated, building his “Frankenstrat,” inventing a floating whammy bar, securing patents, changing guitar thinking. And he was self-taught. —K.G.

Key Tracks: “Eruption,” “Ain’t Talking ‘Bout Love,” “Hot for Teacher”

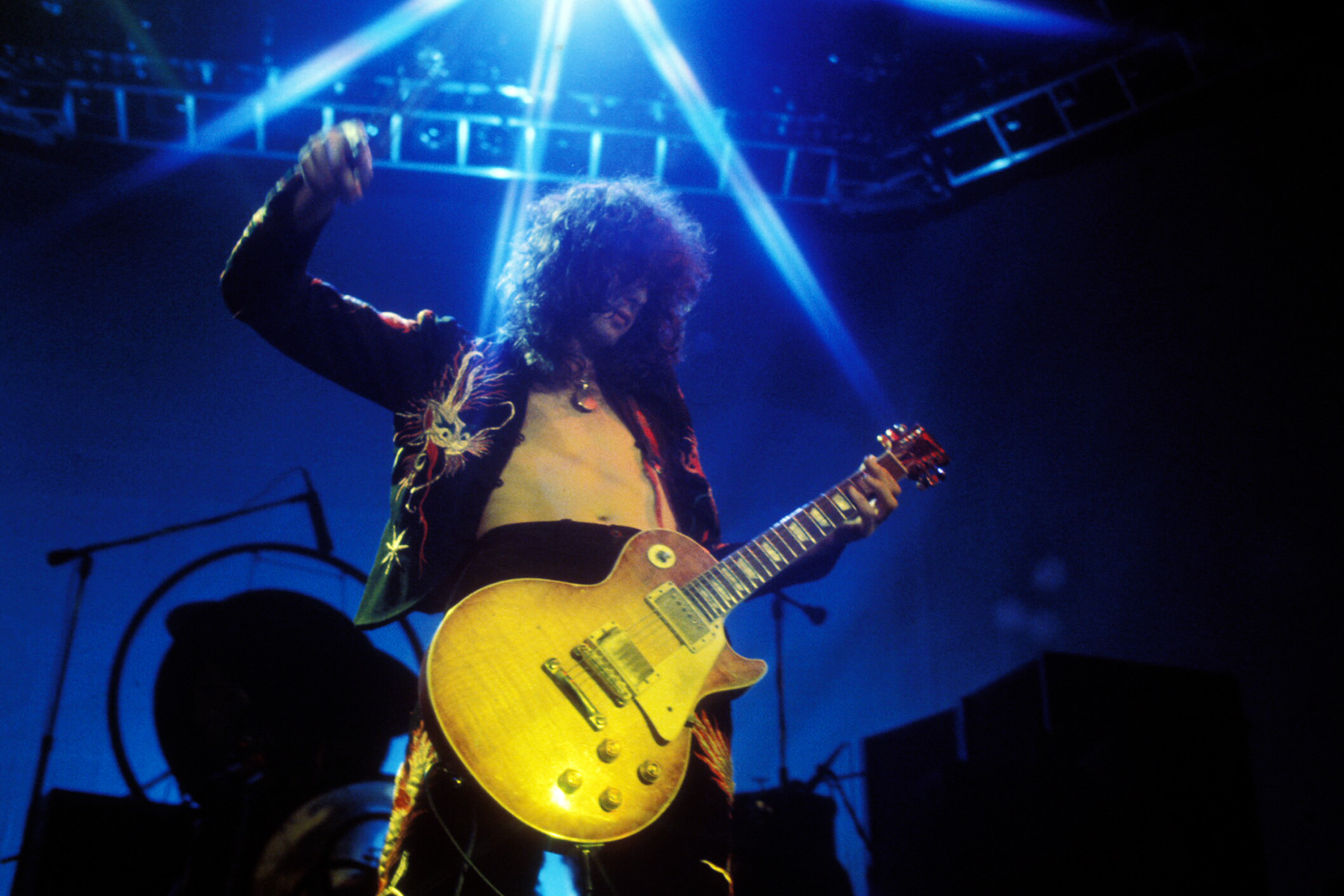

Jimmy Page

Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin performing at Earl's Court, showcasing his legendary riffs and his iconic stage presence

Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin performing at Earl's Court, showcasing his legendary riffs and his iconic stage presence

Before Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page impacted rock through the Yardbirds and session work in London. In his early twenties, Page was the go-to guitarist for the Who, the Kinks, Donovan, Marianne Faithfull, and more. In 1968, he became a rock guitar god forming Led Zeppelin with Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham.

With Led Zeppelin, everything about Page became legendary—dragon suit, occult obsession—but his riffs reigned supreme. “Communication Breakdown” or “In the Evening” riffs are instantly memorable. “A riff should be hypnotic, played repeatedly,” he told Rolling Stone in 2012. His playing also had delicacy, like fingerpicking on “Going to California” or “Stairway to Heaven.” “He transcended guitar stereotypes,” Aerosmith’s Joe Perry said. “Follow guitar in ‘The Song Remains the Same,’ it evolves—louder, quieter, softer, louder again. He wrote, played, produced—no guitarist since Les Paul can claim that.” —A.M.

Key Tracks: “Achilles Last Stand,” “Kashmir,” “No Quarter”

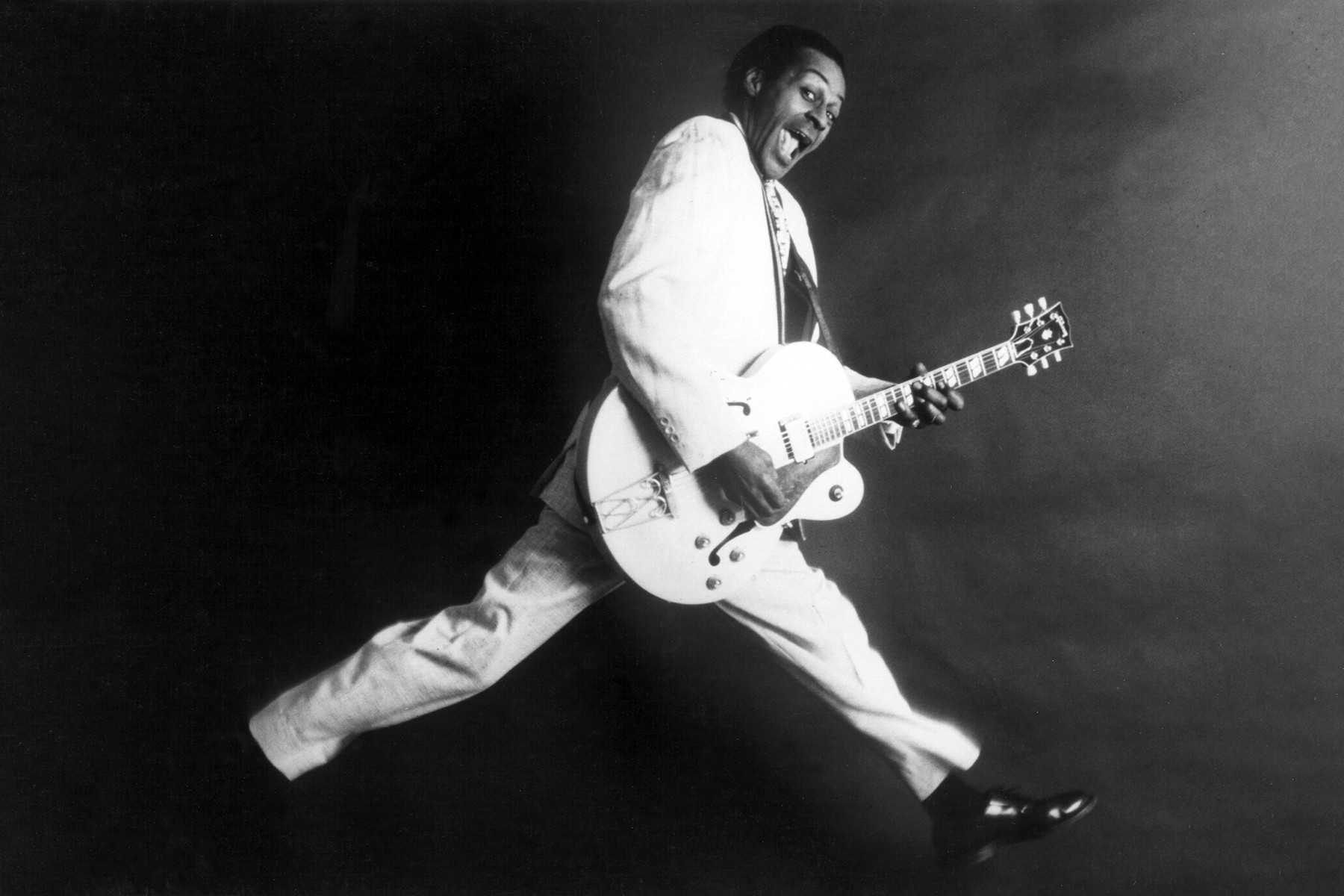

Chuck Berry

Chuck Berry posing with his Gibson guitar in 1958, inventing rock and roll guitar and defining the genre's sound

Chuck Berry posing with his Gibson guitar in 1958, inventing rock and roll guitar and defining the genre's sound

Chuck Berry didn’t just invent rock & roll guitar—he perfected it. His intro to 1956’s “Johnny B. Goode”—an 18-second six-string manifesto—is the definitive guitar-hero anthem. He fused blues and country, boogie-woogie and hillbilly twang, creating high-speed electric flash—rock & roll. Every American music tradition is in Chuck Berry’s guitar. Keith Richards called him “the granddaddy of us all.”

A St. Louis hairdresser, his 1955 debut hit, “Maybellene,” for Chess Records, revolutionized music. Inspired by Bob Wills’ “Ida Red,” he created something new, igniting the world. He defined rock & roll with genius hits: “Roll Over Beethoven,” “You Can’t Catch Me,” “Little Queenie,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man.” His riffs begat the Beatles and Stones, Hendrix and Zeppelin. Imprisoned in the early 1960s, he wrote the ironic “Promised Land.” By Woodstock, he celebrated his hippie fans with 1970’s “Tulane.”

“Nothing new under the sun,” Berry said in 1987’s Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll. Of his playing: “Just a washboard of time passing.” A poetic summary of Chuck Berry’s achievements. —R.S.

Key Tracks: “Maybellene,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man”

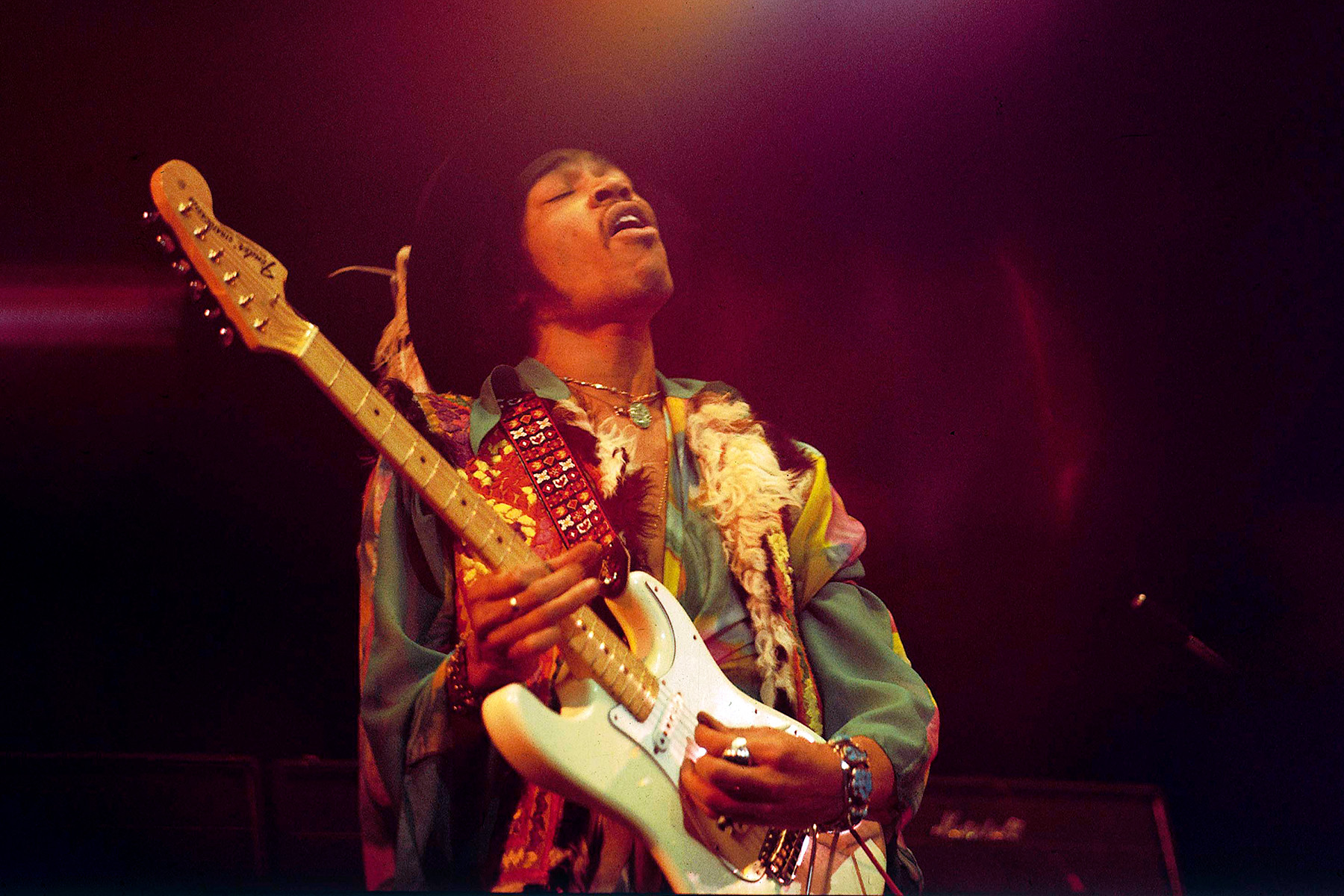

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix performing at Royal Albert Hall, 1969, lighting the way for future guitarists and solidifying his place as the greatest of all time

Jimi Hendrix performing at Royal Albert Hall, 1969, lighting the way for future guitarists and solidifying his place as the greatest of all time

Jimi Hendrix setting his Stratocaster ablaze at Monterey Pop is iconic. A showman playing with teeth or behind his back, beneath theatrics was a master. His eight-year career continues to inspire lifelong study. Hendrix sang, but his guitar was the voice. He popularized feedback, invented blues-psychedelia, influencing rock, metal, funk. Hendrix was eloquent in playing and words. “Wah-wah is great because it has no notes,” he told Rolling Stone in 1968. “Vibrato and drums evoke loneliness, frustration, yearning. Like something reaching out.”

In a segregated music era, Hendrix—a Black artist awing white crowds—was seismic, shattering barriers. Decades after death, his audience grows. “Jimi Hendrix exploded rock music’s possibilities,” Tom Morello said. “Impossible to imagine Jimi now. Elder statesman? Sir Jimi Hendrix? Vegas residency? His legacy as the greatest guitarist is assured.” —A.M.

Key Tracks: “Purple Haze,” “Voodoo Child,” “Little Wing,” “The Star-Spangled Banner”