If you’ve ever been captivated by the harmonious sounds of an orchestra or the intricate melodies of a string quartet, you might have noticed the elegant f-shaped holes carved into instruments like violins. These distinctive cutouts, known as f-holes, weren’t originally designed for electric guitars. In fact, their history traces back to the violin family, long before the advent of the modern six-string guitar.

The story of the f-hole is one of evolution and acoustic ingenuity. The earliest known examples of f-holes graced instruments crafted by pioneering violin makers Andrea Amati, Gasparo de Salo, and Pietro Zanetto in the mid-16th century. Prior to this elegant f-shape, instrument makers experimented with simpler designs, utilizing crescent or “C” shaped holes. Delving even further back into history, as far as the 10th century, reveals that bowed lutes featured circular holes in the very location where we now expect to see f-holes. These strategically placed cutouts were not merely decorative; they were fundamentally functional, designed to project sound from acoustic instruments, much like the soundhole on a traditional acoustic guitar.

Over centuries of refinement, these sound projecting cutouts underwent a gradual transformation, culminating in the f-hole design that guitarists and instrument enthusiasts recognize and admire today. This iconic shape gained prominence in the early 20th century, notably with the Gibson Lloyd Loar F-5 mandolin and the Gibson L-5 guitar. The L-5 holds a significant place in musical history as the first modern guitar to showcase what we now consider the quintessential f-hole. But the question remains: why this particular f-shape? Luthiers and instrument designers have pondered this very question for generations, especially considering the seemingly undeniable impact this shape has on enhancing an instrument’s sound.

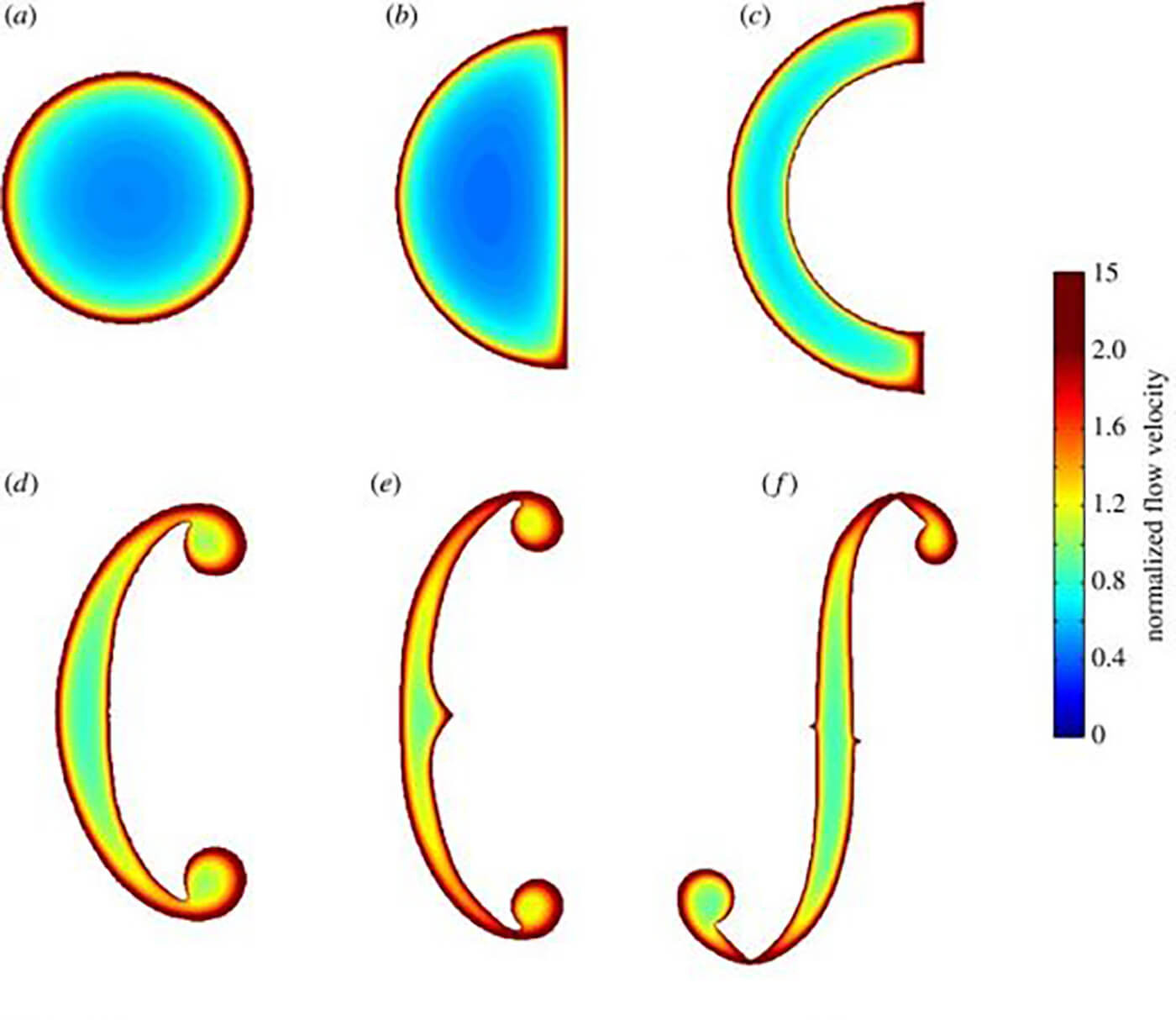

Violin airflow velocity image from MIT

Violin airflow velocity image from MIT

The Acoustic Science Behind the F-Hole Shape

Indeed, the intuitive sense that f-holes enhance sound is backed by scientific investigation. A groundbreaking 2015 study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and published in the esteemed Royal Society of Publishing (RSP), provided valuable insights into the acoustics of sound holes. The research revealed that airflow at the perimeter of sound holes plays a crucial role in conducting acoustics at a significantly higher rate. Interestingly, the study indicated that the depth of the hole is less impactful on sound volume than the perimeter. This means that the edges of a sound hole are paramount in facilitating acoustic resonance. In essence, a longer perimeter, achieved by shaping the sound hole, allows for greater sound projection.

While the precise thought process of the artisan who first conceived the f-hole remains shrouded in history, violin makers and luthiers have long understood this principle on a practical level. Through countless hours of experimentation, they intuitively explored methods to maximize the circumference of the cutout, leading to the evolution and widespread adoption of the f-hole design we are familiar with today.

The evolution of the f-hole is a testament to the remarkable ingenuity of pre-computer era craftsmanship. Luthiers of the past lacked the sophisticated tools to measure air cavity resonance; they relied on meticulous trial and error, guided by their discerning ears. The MIT study even suggests that the f-hole’s development may have stemmed from “craftsmanship error,” highlighting the serendipitous nature of innovation.

This theory holds weight when considering the limitations of the tools available at the time. Replicating a precise cutout, particularly on the natural grain of wood, would have been exceptionally challenging without modern CNC machines. Yet, these seemingly accidental “errors” have had a profound and enduring influence on musical instrument design, shaping the sound and aesthetics of instruments for centuries to come.

Close up of a hollow body guitar with f-holes

Close up of a hollow body guitar with f-holes

F-Holes in the Electric Guitar Era

The landscape of musical instruments underwent a dramatic shift with the advent of electricity. Electric amplification revolutionized stringed instruments, introducing a new realm of sonic possibilities and, concurrently, new resonance challenges for luthiers to address.

Despite these advancements, the f-hole has maintained its presence on some of the most iconic electric guitars ever created. From renowned brands like Gibson, Gretsch, Fender, Ibanez, and PRS, f-holes continue to grace guitar designs, long after magnetic pickups effectively solved the need for maximum acoustic volume in many genres. This raises a compelling question: what purpose do f-holes truly serve on these instruments beyond their undeniable visual appeal? It’s hard to imagine the iconic aesthetics of guitars like the Gibson ES-335, the Gretsch Country Gentleman, or the Fender Thinline Telecaster without their signature f-holes. Their inclusion seems to transcend mere functionality.

The Fender Thinline Telecaster provides a particularly intriguing example. It stands in stark contrast to the fully hollow jazz boxes that historically featured f-holes. Furthermore, even the Thinline Telecaster’s body isn’t entirely hollow; it’s chambered, featuring semi-hollow construction. Given that the Thinline Telecaster was conceived by Roger Rossmeisl, the innovative mind behind Rickenbacker’s 300 series guitars with their distinctive slash-shaped soundholes, why would he opt for the traditional f-hole for the Thinline if not primarily for aesthetic reasons? Let’s delve deeper to uncover the functional role, if any, of f-holes in modern electric guitars.

Fender Thinline Telecaster guitar body showing f-hole

Fender Thinline Telecaster guitar body showing f-hole

The Functional Role of F-Holes on a Thinline Telecaster

To gain expert insight into the function of f-holes on guitars like the Thinline Telecaster, we turn to Tim Shaw, Fender’s esteemed Chief Engineer and pickup guru. His understanding of guitar sound is unparalleled, and he generously shared his perspective on the purpose of the f-hole on a Thinline Tele.

“On fully hollow instruments equipped with f-holes, the movement of the bridge directly drives the top of the guitar,” Shaw explains. “In this scenario, the size and shape of the f-hole significantly influence the resonance and overall tonal characteristics of the instrument.” This is the traditional acoustic function of the f-hole, as seen in violins and acoustic archtop guitars.

However, the situation is different with a Fender Telecaster Thinline. “While a Fender Telecaster Thinline guitar incorporates substantial hollow sections or chambers, the bridge is anchored to a very solid central section of the body,” Shaw clarifies. “Consequently, the bridge doesn’t move the top in the same way it would on a fully hollow guitar.” According to Shaw, in the case of the Thinline Telecaster, “the f-hole is primarily cosmetic. The tonal difference observed in a Thinline is more attributable to the presence of the chambers within the body than to the f-hole itself.” The chambers allow for increased resonance and a lighter body, contributing to the guitar’s unique sonic character.

Fender American Vintage Telecaster Thinline

Fender American Vintage Telecaster Thinline

Stan Cotey, Fender’s Vice President of Research & Development, echoes this sentiment, drawing a direct comparison to the f-hole’s origins. “The earliest applications of f-holes in musical instruments are found in violins, where they serve as an opening to a resonant chamber,” Cotey points out. He further elaborates on the acoustic principles at play: “With resonant chambers, a smaller opening leads to higher pressure around it, resulting in a more resonant sound.”

Applying this to the Thinline Telecaster, Cotey expresses skepticism about the f-hole’s acoustic contribution. “In the context of a Fender Telecaster Thinline guitar, I am not entirely convinced that the chamber itself resonates to a significant degree,” he admits. “Even if it did resonate, I believe its influence on the string’s motion (and consequently, the harmonic content) or its ability to alter the pickup’s physical position relative to the string, in a way that meaningfully impacts the electronic output, would be limited.” Cotey concedes, “One might perceive a difference acoustically, but whether that subtle acoustic variation translates into a discernible change that the pickups can capture is debatable.”

While these expert conclusions are specifically focused on the Thinline Telecaster, they can likely be extrapolated to other guitars where the bridge and pickups are mounted on a solid center block or a substantial portion of solid wood. In such designs, f-holes, while visually striking, may not contribute substantially to the instrument’s amplified tone. The situation might differ for fully-hollow instruments like the Gibson ES-330 or jazz boxes, where the f-hole could play a more significant role in acoustic resonance. However, even in these cases, the tonal impact is likely to be subtle and subjective, particularly when amplified.

Ultimately, does the functional ambiguity of the f-hole on many electric guitars truly diminish its importance? Perhaps not. While it may not be a primary driver of tone in every electric guitar application, particularly in high-volume genres like rock ‘n’ roll, the f-hole retains an undeniable appeal. It remains as aesthetically relevant today as it was on instruments crafted 500 years ago. This enduring presence is a remarkable testament to its timeless design and a graceful nod to the rich history of musical instrument craftsmanship.